On the one hand, there is James Joyce’s classic novel Ulysses, a book that has been described as a “complex masterpiece,” with its manifold overlapping themes, rich symbolism and a vast and colorful cast of characters.

On the other hand, there is Patrick Fitgerald’s play Gibraltar: An Adaptation after James Joyce’s Ulysses, to be presented Saturday at 5 p.m. at Plays and Players, which does something both brave and fascinating. Gibraltar plunges deeply and directly into what Fitzpatrick believes is the novel’s heart: the complex, bittersweet love story of protagonist Leopold Bloom and his wife Molly.

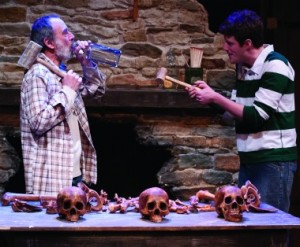

The play takes its name from the birthplace of Molly Bloom, played by Cara Seymour. Seymour actually plays several other roles, including the muse, her husband’s deceased Hungarian father Rudolf Virág, Gerty MacDowell (a young girl Bloom encounters on the beach), and, at one or two points, the Blooms’ cat.) Fitzgerald portrays Leopold Bloom. The play premiered in New York in 2010.

Artist Rob Berry and the crew of Throwaway Horse LLC, creators of the online comic Ulysses Seen , were instrumental in bringing the play to Plays and Players. (Read the blog post.)

I’ve previously owned up to my ignorance of Ulysses. And so I have to admit, I was looking to Gibraltar as a gentle, accessible introduction to Joyce’s Dublin and Leopold Bloom’s travels about the city on that single day, June 16.

And so, in some ways, it was just that. It’s not hard to get a grasp on the broad outlines and themes, although at times it can be hard to focus in on specifics because the lines, derived from the language of the novel, come fast and furious. Consequently, some of what transpires onstage is hard to follow.

Still, hang in there, Ulysses newbs, and you’ll catch snatches of Joyce’s language and you’ll gain precious insight into what makes at least these two characters tick—or as much as they themselves have been able to figure out.

It’s hard for me to imagine a more challenging acting assignment, but Fitzgerald and Seymour are more than equal to the task. Fitzgerald’s passion and energy shine through. He makes the stage, with its meager props—a bed, a set of stairs, some dishes and a tea kettle, a hatstand and a Victrola—seem much larger than it really is. We cease to see props; instead, we begin to see Leopold Bloom, his life and his world through the actor’s eyes.

Seymour is a revelation, particularly as she delivers Molly’s soliloquy. It’s from the final chapter of Ulysses, and it takes up most of the second half. The lines are delivered from a squeaky bed at the far right side of the stage—the bed Molly shares with Leopold. Seymour opens the window wide onto Molly’s fundamental humanity as the character takes stock of her life and her relationship with Leopold—reminiscences tinged with longing and regret. As the monologue continued, you could sense that so-called “fourth wall” actors talk about becoming ever more permeable and, finally, dissolving into thin air.

I would never suggest that Gibraltar is easy going. The Sound of Music, it is not. Still, as the week in which Bloomsday is celebrated comes to a close, take the opportunity to see what two very talented actors can do with Joyce’s challenging masterwork.

Location:

Plays & Players

1714 Delancey Pl

Philadelphia, PA 19103