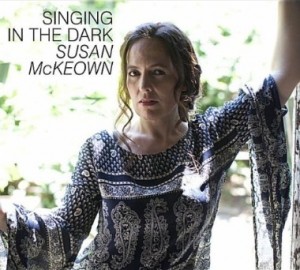

The defining moment of “Singing in the Dark,” Susan McKeown’s moving meditation on the relationship between deeply debilitating mental illness and soaring creativity, comes toward the end of the recording, in a musical adaptation of the Welsh poet Gwyneth Lewis’s “Angel of Depression.”

The words McKeown sings, Lewis’s words, are brutally unsentimental: “Don’t say it’s an honour to have fought with depression’s angel. It always wears the face of my loved ones as it tears the breath from my solar plexus, grinds my face in the ever-resilient dirt. Oh yes, I’m broken but my limp is the best part of me. And the way I hurt.”

When McKeown hurls herself into the word “broken,” she tears through the upper registers like a razor blade through silk. In that single harrowing moment, you can begin to see depression for what it is at its worst, a soul-destroying cancer.

This is strong stuff, in an album full of strong stuff. In “Singing in the Dark,” McKeown and her musical colleagues Frank London and Lisa Gutkin take on the daunting task of putting difficult words to music. The album celebrates the work of poets such as Anne sexton, Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill and and Theodore Roethke. Lord Byron makes an appearance. So do Leonard Cohen and Chilean singer-songwriter Violetta Parra. A recording industry pitchman might describe it as a tribute to troubled souls. It is far more than that.

McKeown says she was inspired to make this album after reading Kay Jamison’s book, “Touched with Fire: Manic-Depressive Illness and the Artistic Temperament.” She also met with familiy members and friends of those suffering from mental illness, and she tapped into the melancholic themes that run like a dark vein through much of her native Irish music. Recording began in a studio on Ireland’s Achill island in August 2008. Thus emerged McKeown’s exploration of mental illness as the wellspring of creative genius.

The source material is indisputably rich: Take, for example, Anne Sexton’s “Her Kind,” in which the poet casts herself in the role of madwoman-witch: “A woman like that is not a woman, quite. I have been her kind.” Or Roethke’s poem, “In a Dark Time,” which ponders life at the extremes but ends on a transcendent note: “A man goes far to find out what he is—Death of the self in a long, tearless night, All natural shapes blazing unnatural light.”

Most of this material is not, by nature, “hummable.” None of this would work if the music didn’t just hold together, but hold its own with the world-class poetry. This, it does—in spades.

Take, for example, “The Nameless One,” by 19th-century Irish poet James Clarence Mangan. With verses like the following, it’s hardly upbeat:

“Him grant a grave to, ye pitying noble,

Deep in your bosoms: there let him dwell!

He, too, had tears for all souls in trouble,

Here and in hell.”

Amazingly, McKeown and colleagues deliver a wonderfully folky tune to accompany those words. The bouncy banjo treatment reminds me of Woody Guthrie’s “Gonna Get Through This World” on the group’s 2006 Klezmatics collaboration, “Wonder Wheel.”

“The Crazy Woman,” based on the poem by Gwendolyn Brooks, is a revelation. If you think about the opening lines of the poem, “I shall not sing a May song. A May song should be gay. I’ll wait until November I shall not sing a May song. A May song should be gay. I’ll wait until November and sing a song of gray,” you may not be able to hear a jazzy little piano lounge tune in it. McKeown and friends did, and it’s a treat.

I was wondering where I’d first heard the dolorous “In Darkness Let Me Dwell,” written by the lutenist John Dowland. It was on Sting’s 2006 CD, “Songs from the Labyrinth.” Susan McKeown’s version will easily make you forget Sting ever tried his hand at Madrigal singing.

“The Crack in the Stairs,” based on the work of Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill, is a bit more challenging, both for the singer and the listener. It’s a dissonant modern piano piece written by Irish composer Elaine Agnew. Give it a chance. It fits the bleak material.

And if not that, there’s more. The Latin standard “Gracias a la Vida,” by Violetta Parra, is a pretty piece. You may remember a Joan Baez version. McKeown’s version of Leonard Cohen’s “Anthem,” is performed with soulful elegance.

That any song on the album would be sung otherwise is unthinkable. McKeown at her best is always balanced right on the edge: fragility on the one side, strength on the other. It’s perfect for material that is so emotionally weighted—and for painting a portrait of life at the extremes.