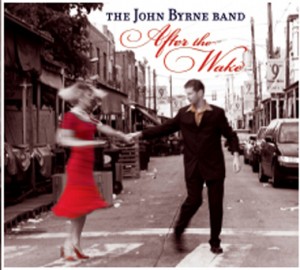

That's John Byrne and his new bride, Dorothy, on the cover of his new CD. Photo by Lisa Chosed.

There’s a lot about John Byrne’s latest CD that’s autobiographical, but the line “I was a mediocre singer with a mediocre song” from his paean to Dylan isn’t. Not by a long shot. In fact, it’s hard to understand why Bryne, who grew up in a family of ballad singers in Dublin, didn’t come to music until he was in late teens.

“When I was a teenager, my obsession was playing football, which kind of gave me an out,” he says, explaining why he had no party piece when his parents and grandparents were warbling theirs in the parlor. “They just said, ‘He’s a footballer, that’s what he does.” He laughs.

Byrne has immortalized those evenings at his grandparents’ house in the track, in “Various Verses,” on “After the Wake,” his first CD effort since splitting from longtime partner (and brother-in-law) Patrick Mansfield with whom he was “Patrick’s Head,” a Philadelphia-based group that played to sold-out crowds in some of the city’s jewel-like acoustic venues like World Café Live and The Tin Angel.

From the opening chords, you know the song is going to grab your heart. In his handwritten liner notes on the song, Byrne admits, “the thing I miss most about being home are the nights when the whole family would gather and sing songs. There’d be parents, grandparents, brothers, aunts, uncles, and friends all singing their own versions of the songs they loved, the songs that spoke for them and through them. These songs and singers will always be my greatest inspiration.”

Those same inspirations appear again in other tracks, like Old Man’s Disguise, in which Byrne muses on how much like his father he’s become. “Like any teenage boy I butted heads with my dad,” he says. “But as you get older you get wiser and begin to see things from their perspective. You look in mirror and see you’re getting more and more like them physically. I have the same mop of curly hair as my dad. This song is about understanding what your folks are as people. You don’t often see them as people like you, but as you come to understand your own flaws, you come to understand theirs too. “

“Midnight in Dublin,” a song about wanting to call home but having to be mindful of the time difference, reinforced the idea that John Byrne gets occasionally homesick. “The homesickness is always there,” he admits. But he’s clearly put down roots in Philadelphia. Last year, he married Dorothy Mansfield and it’s his new bride—dressed in red—he’s dancing with in the Italian Market that serves as the cover photo of “After the Wake.”

“We took dance lessons for our wedding and it was amazing how much I reall enjoyed it,” he says, still sounding a little surprised. “It really fit the morning after feeling we were going for—‘after the wake,’ celebrating the life of somebody and hopefully moving on.”

Byrne first came to the Philadelphia area as a teenager. “I went where every Irish person went in the ‘90s—Wildwood,” he laughs. “The first stage I ever played on was in a bar at the shore.”

He didn’t arrive as a performer. His first job was running the go-kart rides on the boardwalk “14 hours a day, seven days a week, for minimum wage. And I thought it was a great job. You could go to the bar afterwards and the all-you-could-eat breakfast place after that.”

One of his songs, Already Gone, is set in Wildwood in the winter. It’s a “break-up” song with the memorable line, “I used to wallow here, with the men I followed here.” Anyone who’s ever gone to the Jersey Shore off season will pick up the mood immediately. “After I moved here and went to visit the shore towns in the winter, I felt that tremendous sense of melancholy and hibernation of the locals that exists for the months the tourists aren’t there. They’re sitting in the bar just getting through the winter, keeping tabs on Memorial Day,” says Byrne.

He caught the American folk music bug while he was here—he’s Dylanophile and one of his songs, Boys, Forget the Whale, is a tribute to his hero. After leaving college in Ireland (where he studied electrical engineering), Byrne returned to the US to try his hand at performing. But he didn’t want to be just another Irish act.

In fact, in the beginning, he tried to avoid Irish music altogether until bandmate Patrick Mansfield talked him into adding a few songs to their playlist. “Even now I’m very selective about the Irish songs I will and will not do,” Byrne says. “I won’t play ‘Oh, row, the rattlin’ bog’ for example.” He laughs. “At some gigs I was asked to play pro-IRA songs and I didn’t want to go down that road either. One of the ones that got me the most was ‘The Unicorn Song’ [by the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem]. I don’t know how a unicorn song got all mixed up with Irish music. I’d never heard it. I’d say, ‘I have no idea what you’re talking about. Are you sure you don’t mean ‘The Leprechaun song.’ Then I heard a tape of it. I was horrified.”

When he heard he was going to share a stage with Tommy Makem at the Long Island Irish Festival, he says he was ready. “I was going to say, ‘So, The Unicorn Song, lads. I have to ask and I hope you’re going to tell me this was your manager’s idea.” Unfortunately, we’ll never know: the festival was cancelled.

That’s not to say Byrne had rejected the Irish sound altogether. The most autobiographical songs on his CD have a Celtic lilt and one, The Ballad of Martin Doyle, is a trad song in the making. Traditional songs were all new once, after all.

“That song came from my uncle, David O’Brien, who works with a nonprofit organization in Northern Ireland that is trying to bring communities together,” he explains. “He tells this story when he’s trying to show people from different communities that they have more in common than they have differences.”

It’s the true story of an Irishman named Martin Doyle who joined the British Army to fight in World War I, lured by the promise the British made to the Irish that if they did the patriotic thing, the British would consider home rule. After his service, for which he was highly decorated, Doyle returned to Ireland—a post-Easter Uprising Ireland, where those who were martyrs to the free Irish cause made anything British very unpopular. He and the other World War I veterans from Ireland came home to less than a hero’s welcome.

Though Doyle joined the Irish Republican Army and again fought bravely—this time against the British–at his death he chose to be buried in his British World War I uniform. “When David was telling me this story, he asked me, ‘What do you think?’ What I think is that Doyle was trying to honor the Irishmen who fought in World War I and were betrayed by both the British and their own people,” says Byrne. He chose his British uniform, as Byrne writes, because it was “the uniform of another war that treated us like men.”

His uncle encouraged him to write a song about Doyle. “Usually, I can’t just write about something, but this one just came,” he says.

He’ll be playing it—and other songs from “After the Wake”—at his World Café Live CD party on February 20 (better get tickets now—it’s almost sold out). Joining him on stage will be recent transplant, singer-songwriter Enda Keegan, and Byrne’s brother, Damian, also a musician.

“After my grandfather passed on, those music nights at the house got less and less frequent, but Damian really took up the mantle and started them again,” says Byrne. “He and his group of friends get together at somebody’s house and do mostly ballad singing, like we did when we were younger. I’m really looking forward to performing with him onstage.”

You can also catch John Byrne and The John Byrne Band at O’Donnell’s at 139 North Broadway, Gloucester City, NJ, (just over the bridge from Philly) on Friday, February 12, and February 19, or at Slainte, at 30th and Market in Philadelphia, on February 15 and 25.