Tom Reing, artistic director of the Inis Nua Theatre Company, recalls the moment when the curtain came down on one of the earliest performances of Enda Walsh’s dark comedy, “The Walworth Farce.” He looked at his four actors and thought to himself, “it looked like they had just run a marathon.”

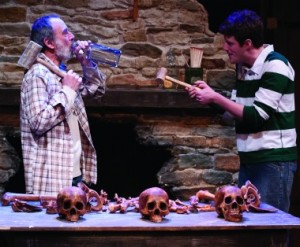

“The Walworth Farce” is a study in complexity. It is a play within a play in which an Irish father and his two sons, who left Cork for a dismal life in a London council flat, daily re-enact the stories behind that flight … stories that are not all true. This bizarre performance is interrupted by the arrival of a supermarket employee toting a bag of groceries one of the sons left behind at checkout.

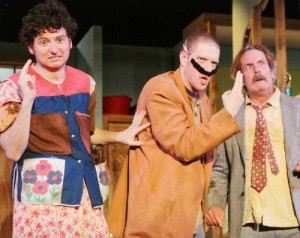

To hear Reing tell it, it’s easy to understand why this play exacts such a toll on the actors. Bill Van Horn plays Dinny, the father; the sons are played by Harry Smith as Blake and Jake Blouch as Sean. Hayley is played by Leslie Nevon Holden.

“‘Farce’ is very quick. If it’s slow, the comedy doesn’t work. And you have these eruptions in the play within the play. There’s very high emotion, and very high-tension themes. The actors are running around and moving from room to room to do different scenes. One of the actors (Harry Smith) has to play all three women, and he has conversations with himself.”

Even the set is complex, he says.

“It takes a lot of work to make their flat look decrepit. These guys don’t clean… it’s three men. The set has a working sink and a working refrigerator. It has a tape recorder that they use on stage. There is a wireless signal in it, and it’s connected to the computer that is connected to our light board and sound.”

There are plenty of props, too, courtesy of Reing and a March trip to Dublin. While there, he packed a bag with Tesco (a supermarket chain) bags, spreadable cheddar, Mr. Sheen (a floor and furniture polish), and Pink Wafer biscuits.

Reing regards “Walworth” as a natural for Inis Nua, which presents contemporary works from Ireland, England, Scotland and Wales. The company previously presented Walsh’s harrowing “Bedbound.”

“Enda Walsh is really hot right now,” says Reing. This play seemed like another great example of his work. It happened serendipitously. He (Walsh) was just nominated for a Tony for his stage adaptation of ‘Once.’”

Reing finds the theme of “Walworth” fascinating. We all tell ourselves stories about our lives, but those stories don’t necessarily reflect the whole picture. “You embellish,” he says. “You tell the story so it’s favorable to yourself.”

So maybe it isn’t the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. The complete, unvarnished truth about ourselves might just be too hard to live with. One line from the play sums it up best for Reing:

“‘It’s my truth, and that’s all that matters; it’s what you do to keep going on.”

The play runs through May 27 at First Baptist Church, 1636 Sansom St., in Philadelphia.

Tickets here:

http://inisnuatheatre.ticketleap.com/walworth-farce/#view=calendar