“Mr. Leopold Bloom ate with relish the inner organs of beasts and fowls. He liked thick giblet soup, nutty gizzards, a stuffed roast heart, liver slices fried with crustcrumbs, fried hencod’s roes. Most of all he liked grilled mutton kidneys which gave to his palate a fine tang of faintly scented urine.”

~ James Joyce, “Ulysses”

His name is Hamlet, but his passion is “Ulysses.”

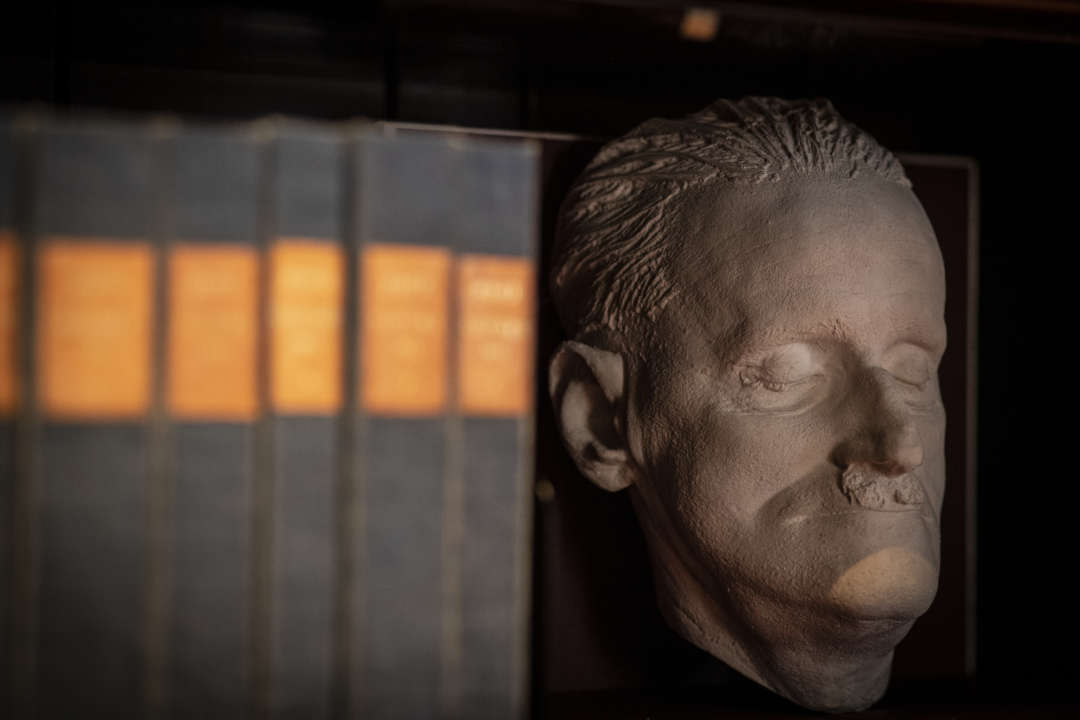

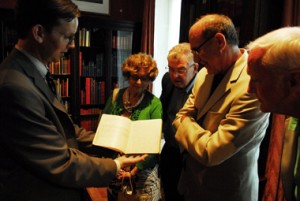

Lucky luncheon goers get up close and personal with Joyce's handwritten manuscript of "Ulysses," which is owned by the Rosenbach Museum. Director Derek Dreher holds the manuscript in the library, which remains dark to protect the books.

For the past seven years, Jim Hamlet, CPA, has served on the committee—two years as its chairman—that brings the marathon June 16 Bloomsday reading of James Joyce’s “Ulysses” to the Rosenbach Museum in Philadelphia.

“Ulysses,” considered one of the best English-language novels of the 20th century, chronicles one ordinary day—June 16—in the life of Joyce’s main protagonist, Leopold Bloom, a modern-day Odysseus who wanders the streets of Dublin, encountering character after character. Its 18 chapters each bear the title of one episode in the life and adventures of Homer’s epic hero, Ulysses, on which Joyce based his work.

While the National Library of Ireland is one of the major repositories in the world for all things Joyce, there’s a coveted, autographed, handwritten copy of the manuscript that calls the Rosenbach Museum home, making it particularly suited to hosting the yearly readings.

Hamlet, his late father, and his son, Michael, have been volunteer readers in past years. This year, he knew he was going to miss it because of an out-of-town work commitment.

So instead, the day before Bloomsday, he was tucking into steak and kidney pie—a tribute to the breakfast enjoyed by Bloom—and other Joycean-inspired dishes prepared by the chef at The Bards for a luncheon at the Rosenbach, sponsored by the John Henry Newman Foundation and Joyce’s alma mater, University College Dublin. Each year, the Rosenbach focuses on a theme related to the novel; this year’s was food, a logical choice for a book that’s a feast of words, many of them about food. Guest speaker for the luncheon was Professor Declan Kiberd, chair of Anglo Irish Literature and Drama at University College Dublin, who explores Joyce’s food themes in his book, “The Art of the Everyday in Joyce’s Masterpiece.”

Hamlet, who does audit work for the Rosenbach and several other museum clients, is keenly aware most people consider a CPA rubbing elbows with Joyce scholars as surprising as finding capers instead of raisins in your oatmeal.

“Most people ask me why I’m so dedicated to Ulysses because I’m a CPA and mostly English majors read the book, but I love Irish literature,” says Hamlet. He had read Joyce, but, he confessed, until he became involved with Bloomsday had never tackled the door-stop-sized “Ulysses” which is famously considered difficult to read, in part because of its stream-of-conscious form and the hundreds of puzzles and allusions that Joyce deliberately inserted “keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant,” guaranteeing his “immortality.”

But when Hamlet volunteered at the Rosenbach, he jokes, he felt he “had to” read the book, as daunting as it seemed. To make it a little less of the chore he thought it was going to be, he took a class with then University of Pennsylvania Joyce scholar, Vicki Mahaffey, PhD, author of “Reauthorizing Joyce” and “States of Desire: Wilde, Yeats, and Joyce and the Irish Experiment.”

“It took us eight months to read it, chapter after chapter, and Vicki helped us get the references and when we got to parts where we had no idea what was happening, she’d help us get over them. The best advice she gave us was ‘If you don’t understand it, keep going, keep going.’”

He was glad he did. Today he describes the novel that probably thwarts more than it impassions in the same way some people describe the latest Michael Connelly thriller. “It’s really a great yarn,” Hamlet says. “It has so many moving parts. Each chapter reflects the story of Odysseus, but what sets it apart is how he tied that story back to ordinary Irish life.”

And seven years of planning the Rosenbach’s Bloomsday festivities has altered how Hamlet looks at the book’s complexity. “In the past we’ve shown movies, had plays, and one year we had a dance troupe do an interpretive dance of the novel. If you think the book’s confusing,” he said with a laugh, “try looking at a modern dance interpretation.”