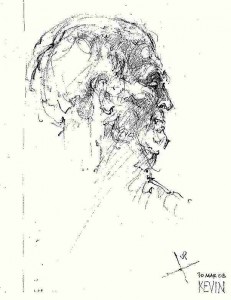

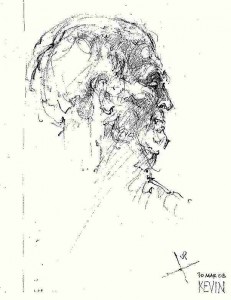

Kevin McGillian © Ted Watson

For more years than he can remember—practically since the Plough and Stars opened in the former Corn Exchange in Philadelphia’s Old City—architect Ted Watson has whiled away countless Sunday afternoons applying his well-honed visual skills to something very unlike the design of buildings. Instead, he takes pencil and pad in hand to capture in exquisite detail any and all aspects of ordinary life in one of Philadelphia’s most popular Irish pubs.

During the week, as an executive associate for Heery Design, Watson works on a range of architectural projects, including schools, health care facilities, and extended care and high-end retirement communities such as the Walnut Street Theatre Tower project. But on Sundays, he strolls a few blocks from his home in Old City over to the Plough to soak in the local color and translate it into unembellished black and white.

Bar patrons, diners, waiters and waitresses, brass beer taps, piles of crumpled napkins—they all find their way onto the pages of his sketchpads.

But if you’re leafing through the bright white pages looking for a recurring theme, a favorite quickly emerges: It’s the fiddlers, flutists, pipers and accordion players who meet every Sunday afternoon at the Plough for a free-wheeling traditional Irish music session.

Watson doesn’t play an instrument, but he understands and appreciates the energy and the passion that the Plough musicians pour into their reels, jigs and hornpipes.

“I appreciate creative effort above anything else in life,” he explains. “They’re givers. They maybe get a free beer, but they’re here mostly because they love doing it.”

[cincopa AMEAvhqBbqAo]

Irish musicians can be a shy bunch. They’re surrounded by chattering diners, a soccer game is playing on the gigantic wall screen, waitresses bearing drink trays pirouette past, but the musicians are mostly in their own world. Regardless, they don’t seem to mind Ted Watson staring at them.

Says Tom O’Malley, who has played guitar at the session for years: “Ted is part of the group. If he didn’t show up, I’d miss him.”

Perhaps one reason why no one minds is that Watson is completely unobtrusive. He’s average height, his brown hair is flecked with gray. He wears a simple plaid shirt and jeans. He is friendly but soft-spoken. But his Everyman appearance doesn’t explain it all. Watson possesses a sniper’s talent for fading into the scenery, and there’s a skill to that.

Hunched over a glass-ringed high-top table below a second-floor overhang, Watson easily blends into the woodwork. A focused yellow beam from an overhead canister shines down upon his sketchpad, illuminating his head and shoulders. The light refracts through the lenses of his glasses, forming tiny bright puddles on his cheekbones. From his perch, he sits mere feet from the ring of padded stools near the fireplace where the musicians pound out their tunes. Beyond the players, Watson has a bird’s eye view of the whole restaurant—the regulars propping up the bar and quietly sipping their pints, the families and gatherings of friends celebrating birthdays, the bright afternoon rays slanting down through the bar’s 16-foot windows, the dust motes dancing in the sun.

Watson knows what he’s looking for: the contrast between soft light and deep shadow on a fall afternoon—“Those old bank windows are incredible”—or the facial expression of a banjo player totally locked into an old Ed Reavey hornpipe.

And there’s one other element, harder to define, but Watson knows it when he sees it.

“The best thing is, it’s the moment,” he says. “The vitality of the moment is what fills the sketch with its energy.”

Energy might seem like the last thing you’d expect to see in a stark black-and-white pencil sketch. But Watson is highly skilled in capturing emotion. His sketches are not snapshots—they’re character studies, rich in detail and yet, as he says, “not super-realistic.”

Take, for example, one of Watson’s long-ago renderings of Kevin McGillian, a two-row button accordionist and the unassuming patriarch of Philadelphia’s traditional Irish music scene. In the lacy swirls, scribbles and delicate crosshatching, Watson presents meticulous detail while at the same time seeming to fill in only the barest outlines of his subject. On one level, we take in the clearly delineated outlines of McGillian’s prominent, sloping nose and strong, jutting jaw; on yet another level, we see only a cat’s cradle of spidery strokes and soft shading.

The McGillian drawing is one of Tom O’Malley’s favorites: “It’s hard to get a picture of Kevin. It really brings out the best in him.”

Watson is pleased, of course, when someone likes his work, but sketching does just as much for him as it does for his subjects. It’s clearly a departure from what he does, and does well, during the week. “I’m an architect, and people say I like doing this because it doesn’t involve straight lines,” he laughs.

But Watson’s love affair really goes back to when he was 15, in high school. “It was just an interest that I had,” he says. “I did portraits of all the team captains.”

He went on to major in anthropology, with a minor in art, at Franklin & Marshall College. He embarked upon a career in architecture in a roundabout fashion. Around the end of junior year, the chairman of the anthropology department took him aside, noted that he had all these other interests—art, sports, student activities—and suggested that perhaps anthropology might not be the correct career path. The anthropology chair suggested he talk to his art professor for advice … and he suggested architecture.

The professor, who had worked with Frank Lloyd Wright, “had forsaken architecture, or it had forsaken him, for sculpture; he was a very good sculptor. He saw art as a very difficult choice, financially and otherwise, as it surely is. He believed that architecture was a course that should result in a stable, employable life style, and in theory artistic satisfaction. He believed that my ability in sculpture and art would be applicable, as it was once for him.”

Watson went on to study at Penn, in the waning years of the great Louis Kahn.

Throughout his career in architecture, Watson’s love of art—he declines to describe himself as an artist—continued, though he pursued it only on his yearly vacations to Scotland, where he sketched castles and country life. “Then I’d come back here and I wouldn’t draw at all,” he says.

There came a point, though, when he knew that drawing only on holidays was just not enough. In time, that desire to do more led him to start taking in the creative opportunities available to him at the Plough and Stars. The music of the place was particularly appealing.

“Listening for me includes seeing, seeing includes action, trying to reach into the emotion, and energy of the moment. I became aware that I had so many willing, and often unaware, models for my visual research into the anthropology of living.”

Over the years, Watson has developed a kind of symbiotic relationship with those models, who, like him, pursue art for art’s sake. They don’t seek to draw undue attention to themselves, and neither does he.

“The joy of sketching is, it’s just my opinion,” he says. “If I don’t like it, I keep it and learn from it. If I do like it, I might show it to someone.”

[cincopa AgFA4jKUbiIk]