Irish Minister for the Diaspora, Jimmy Deenihan, talking to people at the Irish Center on Wednesday. Behind him: Immigration Center executive direct Siobhan Lyons.

The latest donor to Philadelphia’s Irish Center fundraising campaign is the Irish government.

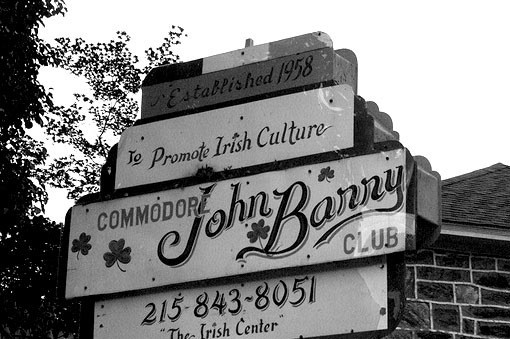

Minister for the Diaspora Jimmy Deenihan, an ex-Kerry footballer whose brand new cabinet post gives him responsibility over the some 70 million people of Irish descent living in every corner of the world, announced this week that the government was allocating $2.3 million to 37 Irish immigration centers across the US for their work in supporting vulnerable populations, including the elderly and the undocumented. That includes Philadelphia’s Irish Immigration Center, located in Upper Darby.

“But I was glad to see that there was a small grant in there of $12,000 for the Irish Center,” said the 62-year-old Fine Gael politician, who is a multiple All-Ireland Gaelic football winner, at a reception—like most Irish gatherings, with fresh baked scone and brown bread—in the center’s Fireside Room on Wednesday morning.

Later in the day, Deenihan met at Stotesbury Mansion near Rittenhouse Square in the city with leaders and members of many of the region’s Irish organizations, including the Irish American Business Chamber and Network, Irish Network-Philadelphia, and the Philadelphia Gaelic Athletic Association, which presented Deenihan with a Philly GAA jersey. He was accompanied by New York-based Irish Consul General Barbara Jones and Vice Consul Anna McGillicuddy.

Deenihan is doing a lap around the globe (he started in the United Arab Emirates, where some 10,000 Irish-born live) in advance of announcing a new “diaspora strategy,” a way to maintain a connection with those who trace all or part of their lineage back to the Emerald Isle. He said he expects to have an action plan in place by January.

If his remarks were any indication, at the top of the list will be immigration reform in the US, particularly as it relates to the estimated 50,000 undocumented Irish living and working in the US. Deenihan met with several local undocumented Irish immigrants in an upstairs room at Stotesbury on Wednesday afternoon, before visiting the Irish Memorial on Front Street.

“Now that the mid-term elections are over, I hope President Obama will look at the authority he has to bring about a fundamental change in immigration rules affecting the Irish,” said Deenihan, while speaking to the estimated 80 people at the Stotesbury event.

The 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, which raised quotas for immigrants from countries such as Latin America and Asia who had been previously disadvantaged, followed the law of unintended consequences. The mission of Boston’s favorite Irish son, Senator Ted Kennedy, the new immigration policy reduced the number of legal immigrants from Ireland. Prior to 1965, about 70,000 were coming to the US; in the decade after, only about 10,000 were permitted to come.

Many countries rely on their diaspora for support—for money, for tourism, and in the case of Israel, said Deenihan, “their survival.” Ireland isn’t the first country to establish a minister for the diaspora, but he said, no other country has the strong connection Ireland has with the US.

“Nearly every family in Ireland has relatives here in America,” he said in his address at The Irish Center. “I have lots of relatives around here. I should have, I suppose, told them I was coming,” he added, to laughter.

“Our connection to you is so strong that though we’re part of Europe,” he said, “we look to support from here in the US.”

Later, I asked him privately about what specifically that connection meant to Ireland. “The diaspora has been very good to Ireland. The recent business investment in Ireland came because of our connection here,” Deenihan said. “But I’m not just looking at what the diaspora can do for us. I’m looking to give back to the diaspora.”

For one thing, he said, he wants to make it easier for Irish Americans to trace their roots. Fewer Americans than ever now identify as Irish, which can erode the link between the two countries and is something, he believes, that a little bit of family history searching could help mitigate. In recent years, the National Archives of Ireland has made both the 1901 and 1911 Census records for all 32 counties available online for free. “I’d like to make more records available,” he said.

As minister for culture, he presided over the development of the website, www.inspiring-ireland.ie, which gathers many of Ireland’s cultural assets under one virtual, searchable roof. For example, you can search by institution and see the portrait of famed playwright Lady Augusta Gregory that hangs in the National Gallery of Ireland or view a page from the transportation register of Cavan gaol (jail) that’s kept in the National Archives.

“I want to build on that site to make this kind of information readily and easily accessed,” he said. “If you give to people, they always give back.”

[flickr_set id=”72157649142557842″]