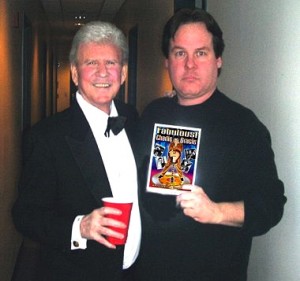

Filmmaker John Foley of Wayne.

A few weeks after 9/11, you couldn’t buy an American flag in this country. They were sold out, flying from flag poles, porch roofs, even car antennas from sea to shining sea. Seven years later, where are they?

Wayne filmmaker John Foley asked himself that same question not long ago.

“I was listening to some people who’d gone on a holiday in Europe and they were joking about how they told everyone they were Canadian. I thought to myself, why? What are you ashamed of? And it dawned on me that what the flag represented had changed since it was hoisted over Iwo Jima in World War II or even over Ground Zero. It had gotten lost. To many people, it had been co-opted or hijacked by the religious right or the Republicans, and all the sacrifices people had made along the way faded into the past and it became a symbol of what’s wrong with this country.”

At the time, Foley was in the midst of filming what would later become “The Color Bearers,” a film examining the history of patriotism as embodied by the symbol of the flag, from the Revolutionary War to the present day, which he also produced with childhood friend Steve Newbert. He’d begun the documentary as a personal tribute to a distant relative, James Seitzinger, a 17-year-old from Schuylkill County who lied about his age to join the 116th Pennsylvania Infantry during the Civil War. On the first day of the battle at Cold Harbor, VA, in June of 1864, the unit’s color bearer—the soldier who carried the flag into battle in front of the troops—was shot down. The young farm boy rushed forward to seize the flag and raise it, dropping his rifle to do so. For his bravery, Seitzinger received the Congressional Medal of Honor.

“When I started looking into it,” says Foley, “I found that of the 3,500 soliders in the entire history of the Medal of Honor, most of those who received the award had something to do with the flag during the Civil War—they were either color bearers or had captured the enemy’s flag. I started asking the experts, what’s the big deal about the flag capture? What it comes down to is that carrying the flag was a dangerous job. It required an inordinate amount of bravery and courage heading into battle, holding just a flag. You’re stepping into battle six feet ahead of your troops, the battlefield is filled with smoke, and there’s the flag popping out of the smoke. There were no radios or telegraphs on the battlefield. The only way to communicate what you wanted your troops to do was, as an officer, position yourself behind the flag and tell the color bearer what you wanted the troops to do, go left, right, forward, or back, and they just followed the flag. You became a bullet magnet. The life expectancy of the average color bearer in battle was six months. They had to drop their rifles to pick up the flag, and that’s what Seitzinger did.”

Foley found three other color bearers from the Civil War and not only told their stories, but found living descendants who talked about how their courageous ancestors affected their lives today. For example, the descendants of Union color bearer Ben Crippen—who include a police chief and Desert Storm vet from Guyton, GA—ritually return to the battlefield at Gettysburg to take a family photo under the statue of Crippen, a member of the 143rd Pennsylvanians, who was killed while his regiment was attempting to keep the Confederate army from entering the town. Crippen lagged behind his troops, which were engaged in a rear guard action, and would periodically turn to face the Rebels, only a few feet away, and shake his fist at them. Crippen was gunned down, but it was his act of defiance that rallied his troops, who kept the Confederates at bay.

But Foley felt the focus on war heroes made the film “too dusty, too History Channel,” so he also talked to other people for whom the flag has held great significance beyond the battlefield, including singer Lauren Hart, who performs the Star Spangled Banner at Philadelphia Flyers home games and never fails to think of her father, announcer Gene Hart, the legendary “voice of the Flyers;” Tim and Brian O’Connor, owners of Humphreys Flags, located across from the Betsy Ross House, which has been making flags since 1805 and created an American flag so large it didn’t fit on a football field; and Scott LoBaido, a New Yorker who painted flags on 50 buildings in 50 states as a tribute to America’s soldiers. Former Eagles star Vince Papale narrates the one-hour film.

Foley, who grew up in St. Dominic’s Parish in Northeast Philadelphia and graduated from Father Judge High School, took a long, circuitous route back to one of his earliest passions, TV and filmmaking. When he entered Temple University in 1974, he was a physics major, but switched to the radio-television-film . Unfortunately, for financial and other reasons, he had to drop out. He never graduated from college, but wound up in the telecommunications business, eventually as the CEO of a company.

But a few years ago, when the telecom industry started to implode, Foley made what seemed to be a good business decision. “One thing that hasn’t imploded, but has actually exploded, is content,” he explains. “Content is on the rise. So about five years ago, I said to myself, ‘Do I want to be scraping by well into retirement in the telecom industry until it’s dead, or do I cut my losses now and chase my dream?’”

The dream won. Today, he’s director of business development for PMTV (Producers Management TeleVision) in King of Prussia, a 20-year-old company that provides mobile facilities and production services for clients as varied as Home Depot and ESPN. He had a brief stopover as the world’s oldest intern too—working gratis for another Philadelphia production company, Teamwork Productions, writing and producing documentaries and TV pilots with an African-American theme.

Life has changed dramatically—in many ways. “I had a little money for a little while, but it’s been scary,” Foley admits. “Right now I’m earning half of what I earned as a CEO. It’s hard. I had a lot of nice rewards rising to the top of the telecom industry, but I’ve shed them now, the boats, the cars. . . .But I have a nice condo in Wayne and where I didn’t see a future in the telecom industry, I see a future now. And did I mention that I’m having fun?”

“Color Bearers” became his resume piece, allowing him to convince his new boss that he should hire a guy for TV production who had no real experience. “If it hadn’t been for this film, I wouldn’t have gotten this job,” he says.

The film, which premiered on June 14 (Flag Day) at the Independence History Museum on Third Street, has also opened his eyes about the ambivalent relationship Americans have with the symbol of their nation, he says.

Some of that began to surface while he was filming. One of the questions he asked each of his interviewees was “What is patriotism?”

“Tim O’Conner of Humphreys Flag, when I asked him that question, Tim went off on this riff on how we were creatures in the trees in Africa, and when we came out of the trees, we got together and basically protected one another. A patriot was someone who gave up his life for his tribe,” recalls Foley. “Well that particular day, I shot the segment on my lunch hour and was dressed in a suit and a tie, and Tim assumed that I was a staunch member of the religious right making a film about the flag. He was convinced that what he said would never make it to the film and he was laughing to himself. Of course, it’s in there.”

Foley laughs, but then suddenly becomes serious. “The fact is, you’re prejudged if you have a flag out. To many people, you’re automatically a hawk, and that is one of the very things we’re trying to combat with this film. Republicans and the religious right don’t own the flag. Americans own the flag. It’s lazy to jump to assumptions about people because of the fact that they’re proud to be an American.”

He wanted “Color Bearers” to restore the flag to its historical significance as a symbol of freedom for people who longed for it where they came from, but never found it until they arrived here.

“I wanted people to make the connection, through the story of the color bearers, that the flag wasn’t something to be ashamed of, to remember what had gone into giving us the freedoms we have,” he says. “You can burn a flag in this country without going to jail. If you want freedom of speech, you have to accept people who don’t believe what you do.”

The film has had a profound effect on those who’ve seen it. At a Temple University “teach-in” conducted by history professor Ralph Young last month, a screening before an audience of students, professors, and non-students, provoked a spirited discussion that went on for 90 minutes. “It was very interesting,” notes Foley, who attended the screening. “The students responded very positively, but people in their 50s and older took us to task for doing anything that glorified America and the flag. They were upset with me that we didn’t show more of the Vietnam era antiwar movement with people burning flags in protest. But we wanted it to be a positive film, and frankly, we only had an hour.”

Foley admits he made a conscious decision not to show flag-draped coffins in the film. “I found a lot of those images on military websites of funerals at Arlington Cemetery, but I felt like I was intruding on people in their deepest pain ever in life To put that into the film and sort of exploit the image felt wrong, and I just decided I wasn’t going to do it.”

What you will see in the film are photos of Foley’s son, Sean, now a Philadelphia police officer, who was deployed to Iraq in 2003-2004. Sean (“now there’s an Irish name for you,” laughs Foley) joined the National Guard prior to the Iraq war, like many young men and women, to make some money for college. “Now, I firmly believe that we were sold a bill of goods by Bush who didn’t do enough work to determine if there were in fact weapons of mass destruction over there, didn’t have the support of our allies, and didn’t really have a good plan. But when I was standing with his sisters and his mother at Fort Dix as he was leaving, I didn’t want to say anything negative to him that might cause him to hesitate at a crucial moment, a hesitation that could cost him his life. You can hate the war and love the soldier—I hope that was the lesson we learned from Vietnam.”

Instead, Foley removed a Claddagh ring he bought in Dublin “that really means a lot to me,” and handed it to his son. “I said, son, you bring this home to me. A year later, he pulled me aside, took the ring off, and handed it to me and said, ‘I told you I’d give it back, Pop.’ I get choked up now as I say this. I will never take this ring off.”

Then Foley, the historian, brought it all back to the flag. Just as he gave his son the ring, historically, soldiers were often given flags sewn by the women of their towns so they could take a little “home” with them to war and they were admonished to “bring it home proudly,” says Foley. “I gave my son the ring for the same reason, to let him know I was with him.”

Carolyn Blashek, founder of Operation Gratitude, the nonprofit group that sends care packages to service people deployed overseas, wants to carry on the tradition in a more modern way. “She called me up and said she had just finished watching the film and couldn’t stop sobbing,” says Foley. “Operation Gratitude has already sent more than 350,000 packages to troops in harm’s way, and they are going to do doing another drive for the holidays and they start packing this month to send packages addressed to 70,000 individual soldiers nominated by people on their website. She wants to get as many copies of ‘The Color Bearers’ to stick into the packages. So far we’ve raised enough corporate and individual sponsorships to send 600 copies.”

Foley says he’d like to donate 70,000 copies, but doesn’t have the money to create that many duplicates. You can help. If you go to the “Color Bearers” website, you’ll find information on how you can donate a pack of 10 DVDs for just $25 (one copy normally costs $24.95). That small donation will help remind a solider that he or she is also a color bearer, a living symbol of the land of the free, the home of the brave.