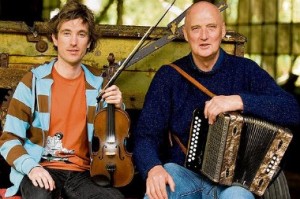

wp-content/uploads/2012/11/lilt-300×200.jpg” alt=”Lilt: Keith Carr and Tina Eck” width=”300″ height=”200″ /> Lilt: Keith Carr and Tina Eck

Anyone who has ever traveled to Ireland knows that German tourists love the Emerald Isle as much as Americans do. (I can remember bumping into a tour bus full of Germans on holiday at the Poulnabrone Dolmen, an ancient tomb out in the middle of one of Ireland’s most remote places, the Burren.)

So from the perspective of Tina Eck, who hails from Travemünde, a seaside resort along the border with Denmark, it is not at all unusual that she plays Irish flute, and is part of a popular duo called Lilt. The traditional twosome, which also features Irish bouzouki and tenor banjo player Keith Carr, is scheduled to play Sunday, November 18, as part of the Coatesville Traditional Irish Music Series. (Note to readers: This concert has been canceled.)

Eck, who now lives in Cabin John, Maryland, works as a radio correspondent covering Washington. She moved to the United States to work for Voice of America in September 1992, around the time of Bill Clinton’s election to the presidency. She had traveled to Ireland several times over the years, so she was familiar with Celtic culture. The music, not so much.

Then, one night in the mid-1990s, Eck visited the well-known Connecticut Avenue watering hole Nanny O’Brien’s, where a traditional Irish music session was going full blast.

“Nanny O’Brien’s was a hangout for journalists. You’d sit and drink, and talk politics. It was the first time I had ever heard an Irish session. It was completely mesmerizing.”

Eck resolved to do whatever she needed to do to be a part of that session. She started to teach herself tin whistle, soaking up tunes at the feet of guitarist, session leader and Nanny O’Brien’s owner Brian Gaffney, and others.

“I hadn’t played a musical instrument since I was in 4th grade,” Eck recalls. “I learned a bit of recorder then. But with Irish music, it was unbelievable that you could just sit behind a piper, and pick it all up by ear. You didn’t need to read music. I still can read music a little, but Irish music is truly accessible. You learn the music from your friends. That’s part of the appeal … the whole social thing, you know?”

Eck never did have formal lessons, though she did pick up bits and pieces from other whistle players. At that point, she was content to just keep tootling along on her whistle. But it wasn’t all that long before some of the other players were suggesting that she just might like the Irish wooden flute.

“Everybody said I should, Eck says. “I didn’t want to as I was really happy with the whistle. Then, one night, one of the flute players brought an old Casey Burns flute to the session—it was in a long green woolen sock—and he said, ‘Hold onto it as long as you like, and learn this.'”

It wasn’t long before Eck found herself banging out tunes on the flute. She says she was highly influenced by one of the best Irish flute players on the planet. “I complete idolized Seamus Egan (of the band Solas). To be able to play like him would be so great. That really motivated me.”

As with whistle, Eck learned flute in dribs and drabs from other players. She recalls in particular an informal—really informal—lesson from the great Galway-born Mike Rafferty.

“I asked him, ‘How you play a roll?” and he said ‘You just wiggle your fingers.” End of lesson.

Eck followed up with frequent trips to Ireland to pick the brains of the best at the Willie Clancy, Frankie Kennedy and Sligo summer schools. All of that learning was having the desired effect. She was getting good, and becoming known.

Eck’s musical partnership with Keith Carr—which would lead to the formation of Lilt—began in 2009, and quite by accident. Eck had booked a funeral, lining up guitarist Zan McLeod to accompany her, but McLeod dropped out at the last minute. Eck knew Carr from the Nanny O’Brien session, so she asked him to accompany her, and she quickly discovered that she and this talented bouzouki player were a good musical fit for each other.

“I think it was in the fall of 2009 that we started playing together more,” Eck recalls. “And in 2010, we went into the studio to record a few things, just for fun. I remember, it was in the middle of a blizzard. We sat down for a few hours, and we played what we liked to play.”

Eck didn’t everything on the recording, but she says Capital-area Irish music aficionados had a different opinion. “I think we made 500 copies of that first demo. People loved it. They were just ripping the CDs from our fingers.”

At that point, it became clear that Eck and Carr should formalize their partnership. Then came the question of a name, but Eck had actually thought about that even before a band of any kind became a possibility.

“My husband actually came up with the name ‘Lilt,” says Eck. “He said, if you ever have a group, why don’t you call yourselves ‘Lilt’?” That name stuck with Keith and me, and we began to play together more regularly.”

As to the question of what to play, the answer was obvious: dance music. As she had progressed, Eck had been invited to play in ceili bands. She remembers it being a challenge: “I could barely keep up.” But soon she settled in, and discovered a whole new reason to enjoy playing Irish music, and in particular, a preferred style of play for the then-new duo Lilt.

“I love playing for dances. The dancers fill in all the blanks. I think a hornpipe can sound a little dorky all by itself, but as soon as you have shoes pounding out the rhythm, that’s when the music has lift and energy. So Lilt now is the quintessential dance band. We still do play for dances, but sometimes in performances, we also have step dancers and sean nos (old style) dancers. Not in every tune, not in every piece, but when the dancers get going, it’s not only a crowd pleaser. I get goose bumps.”

You can get your own goose bumps by snagging a ticket for the Coatesville concert.