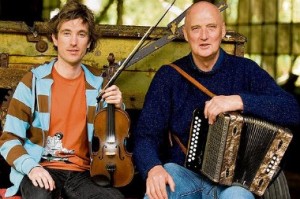

Button accordionist Brendan Begley and fiddler Caoimhín Ó Raghallaigh call their new CD “Le Gealaigh/A Moment of Madness.” If this be madness, there is method in it.

This 12-track recording is a bit of barely controlled wildness. I’m thinking in particular of one live track (“The Green Cottage,” “The Glin Cottage” and “Julia’s Norwegian Polka”) that brings to mind the image of a freight train roaring downhill, going faster and faster until the whole thing threatens to run off the rails.

It never does—but it’s a near thing.

There are a few moments like that on this recording, moments where musical expression could well be sacrificed on the altar of speed. In the hands of anyone less capable, that’s exactly what would happen. But wildness, Begley says, is a hallmark of the West Kerry style of accordion playing—and it’s Begley who seems to be leading this charge. You get the sense that wildness is exactly what these two musicians want to bring out in their tunes.

So yes, it is all a bit mad on occasion, but somehow they maintain their sanity.

We started out talking about a particular set of polkas. We could well talk a good deal more about them. There are six sets of polkas on this recording. As for the rest, it’s a neat little mix of jigs, a pair of laments and one set of hornpipes. Anyway, if you like polkas, you won’t be disappointed. With the exception of the aforementioned runaway train, most of them are well-suited to dancing. A particular favorite is track three—”Sean Keane’s” and “The Ardgroom Polka.” Begley plays the first tune, hitting all those deep, resonant chords, setting the pace. One of the interesting things about this CD is that you can hear the clicking of the accordion buttons on a few tracks. Maybe this isn’t what the musicians intended—it’s not the polished thing to do—but it gives the CD the ring of authenticity. It’s as if you were sitting next to Begley in the circle at a session. It’s almost visual. Ó Raghallaigh jumps in on the second tune, and the two together play with authority and great presence. They draw you in.

You’ll also be pulled in by the laments, “An Chéad Mháirt de Fhomhair” (The First Tuesday in Autumn) and “Na Gamhna Geala,” which Begley performs unaccompanied. Begley’s use of deep, droning chords is very pipe-like. There’s a stark beauty to both tunes.

Ó Raghallaigh gets his own chance to shine on a soaring set of polkas, “Tá Dhá Gabhairín Buí Agam,” “The Glen Cottage” and “I’ll Tell Me Ma.” It sounds like two fiddles playing.

With all the polkas, the jigs almost take a back seat. But not quite. The catchiest, most toe-tapping moments come on a set of jigs, “The Humors of Lisheen,” “The Munster Jig” and “Sean Coughlin’s.” You’re carried along by the rhythmic rising and falling of fiddle and box. It’s a perfect pairing.

With two players so well-matched and at the top of their game, “A Moment of Madness” is essential listening. It’s crazy good.