This week, the British government released a report on the 1972 Bloody Sunday shootings, placing the blame for the 14 deaths that day squarely on British soldiers.

A wall mural in Derry created by Bogside artists commemorating Bloody Sunday.

In an unequivocal apology, British Prime Minister David Cameron called the shootings “unjustified and unjustifiable,” noting that the demonstrators marching through Londonderry that day were unarmed and that the soldiers, who fired more than 100 rounds and killed some wounded marchers at point blank rage, acted in violation of their orders.

This one day of violence led to an escalation of “the troubles” in Northern Ireland which raged on for decades, leaving more than 3,000 dead.

In Derry, the release of the Saville report—which cost $280 million and involved more than a dozen years of testimony from thousands of witnesses—was greeted by cheers. Family members of the slain demonstrators, many of them teenaged boys, expressed relief that, as one said, “the truth has been brought home at last.”

In the Delaware Valley, many Irish-Americans, particularly those with a link to Northern Ireland, were also relieved—but with reservations. We asked some of them to share their feelings on this landmark event.

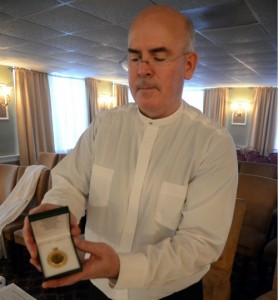

Seamus Boyle, Philadelphia, national president, Ancient Order of Hibernians

A native of County Armagh who emigrated to the U.S. in 1954 as a young boy, Boyle returns every year to march in the Bloody Sunday commemoration parade and has come to know some of the families of the slain protesters.

“[The Report] is great news but it’s about 38 years too late. It’s something that at least gives the families closure and now they can rest in peace. It’s good that it did come out, and great that we got an apology from the British government—the first ever—but at the same time they give you an apology they said that [former Provisional IRA leader and current Deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland] Martin McGuinness was there with a submachine gun. [The Saville Report, which raises the possibility that McGuinness was armed, said there was insufficient evidence to make any finding on the claim, other than McGuinness did nothing to justify the actions of the British soldiers that day.]

“While it will help give closure to the families, so much has happened over there in past 30 years during the Troubles, it’s hard just to give up and say this is fine. It’s hard to forgive and forget. A guy I know, TJ Carraher, his son was killed at a roadblock. For no reason at all, the soldiers opened fire and killed one son and wounded another. It’s hard for that man to forgive and forget. There was an awful lot of damage and hurt done by British soldiers that wouldn’t have been done if there hadn’t been British soldiers on Irish soil. I know that people say they were there to protect us, but they weren’t there to protect the people; they were there because the British government thought it was their country.

“I was over there in the late ’60s early ’70s. I got married over there in 1970 and built a house. It [the Irish civil rights movement] was just starting when I left to come back here in 1971. Every year, twice a year, my wife and I would go back and we’d be subject to harassment because, I believe, I was very active here and come from a big Republican family. One of the things that sticks out in my mind, is that every time I went home I would say to my mother-in-law, ‘When was the last time there were soldiers on the road,’ and she would say, ‘The last time you were here.’

“When you’d go out to Mass on Sunday they would stop you and hold you back so you would be late. Once, a soldier stopped me and asked for my license. I showed him my license and he didn’t look at it. He looked at me and said, ‘Well, Mr. Boyle, where were you headed for?’ Afterwards, my daughter, who was only five at the time, said, ‘Daddy, did you know him?’ I said, ‘No.’ And she said, ‘Well, he knew you. He didn’t look at your license and he knew your name.

“But the Saville Report is what we’ve been waiting for. The families have been waiting so long and the government kept putting it off, putting up, just hoping it would go away. But the families didn’t want it to go away. They wanted the world to know what happened. Now we do.”

Pearse Kerr, Jenkintown, Freedom for All Ireland officer, Pennsylvania Ancient Order of Hibernians

Pearse Kerr, who was born in the U.S. to Irish parents, was raised in Belfast. One morning around dawn when Kerr, then 17, was sleeping, British soldiers came to his home and dragged him away without explanation. He spent the next week in Castlerea Prison, unable to see family or an attorney, while he was interrogated and tortured.

“The only thing good about [the report] is that it brings some closure for the families. But there’s nothing new about it to the Irish people. They knew it was a murderous action. On both sides of the divide they knew. They were talking about the youths of Derry as though they were a bunch of hooligans when they were a group of young people who had enough of political turmoil. There was such a depth of bigotry and discrimantion, at that point they didn’t have an option except to protest.

“The fact that it took the British government so long to admit it shows what we’re dealing with. Think of how hard it’s going to be to make them hold up to the Good Friday agreement [the peace accord that calls for an eventual united Ireland]. It’s great that they admitted their problems, but at the same time they have nothing to be proud of. It went on for so long and those families suffered.

“When I was 17 I was taken out of my home, yanked out of my bed and they didn’t even let me put on my clothes. My mother was passing my clothes to me as they were taking me down the stairs. I got into a Jeep with just my boxers on. But that wasn’t anything out of the ordinary. There were probably six or seven taken from my neighborhood that morning. I was taken under Section 13 of the anti-terrorism act that allowed them to keep me for seven days for questioning without any legal representation or family visits. That was all part and parcel of the Separate Powers act, laws that they didn’t use anywhere else but in Ireland that allowed for internment without trial. In some cases they would release people and once they were outside the gate they would re-arrest them and hold them for another seven days. This was at the height of their torture program in 1977.

“I suffered a broken wrist, a dislocated neck, fractured ribs, multiple bruises. But in some cases they killed people. They’d be found hanging in their cells and they would claim it was suicide. In on case they threw a guy out of the window three stories up and said he tried to escape. He was beaten so bad his own mother couldn’t recognize him. My perspective of it is that it’s a day late and a dollar short.

“I’m glad it’s finally out in the open. But I don’t have any kudos for them—those families suffered way too long. It makes you wonder how long is going to take to heal the whole situation. After all, that’s just one incident.”

Liz Kerr, Jenkintown, Freedom for All Ireland officer, LAOH Brigid McCrory Division 25

“If you read the report, it’s almost hard to believe—how bad it was, how deep the cover-up was, the lengths that they went to lie for 38 years, while those families suffered for 38 years.

“The worst part was when the Queen gave Derek Wilford [commander of the 1st Battalion of the Parachute Regiment in Derry that day, whom the report says disobeyed direct orders not to send troops into Bogside that day] a knighthood within a year, and the parachute regiment were given medals. If there’s really going to be closure, they’re going to strip them of their honors. Those honors were given to them based on a lie. And the moment they got those awards was truly insult to injury to those families. It’s one more thing that will have to happen for them to be completely honest. The victims were mostly high school age boys, 17 years old, and probably looked younger. They were executing teenaged boys.”

“I was glad to see David Cameron’s coming out with the report, especially since he hasn’t been in office long. It’s a good sign. I’m hoping it’s a good sign. He was pretty harsh in his comments—that it was unjustified and unjustifiable—and I’m glad it took it to that level.

“Bloody Sunday really moved the civil rights movement into a war, and I’m hoping the release of this report can be another watershed moment, and that based on this we can move toward a united Ireland.”

Patricia Noone Bonner, Longtime Member of Irish Northern Aid and Clan na Gael

“I don’t care how long a time it’s been. They had to get it done.

“People were killed for no reason. They (the protesters) didn’t start it. They were not carrying weapons. They were just struggling for civil rights. I remember that time well. I’m sure I heard about it on television. We were all up in arms. In my opinion, I am sure that’s why the armed struggle started.

“From the point of view of the families, it (the report) may help move things forward. but still … how do you ever get over losing anybody, especially a child?

“Should there be prosecutions? I don’t know. I don’t think the soldiers should be. It’s the higher-ups who should be prosecuted. Those soldiers would not have fired if someone had not told them to.”

John Ragen, President of the Irish Club of Delaware County

“For my generation (he’s 32), we’re learning about it. It’s our history and definitely something we should all know. Why do I care? It’s’ something that was such a travesty, it should be made public. And if you don’t learn about it, history has a tendency to repeat itself.

“The report coming out shows that the British were not there for the people, they were there for the land. I’m sure it (the report) will bring people together. The Protestant ministers have already extended their hands out to the families of the people who were killed or injured. (Read the story in the Irish Times.)

“The prime minister’s apology was well-written. It may be enough for a lot of people, but the military who were involved should be held accountable. The soldiers should be brought up on perjury charges, at the very least.”

Jeff Meade also contributed to this report.