We’ve just suffered through one of the worst winters in memory. I still have a 50-pound bag of rock salt standing by in the garage. I don’t believe it’s really over.

We’ve just suffered through one of the worst winters in memory. I still have a 50-pound bag of rock salt standing by in the garage. I don’t believe it’s really over.

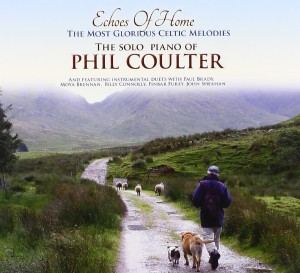

I’ve been listening to “Echoes of Home: The Most Glorious Celtic Melodies,” a relatively new release by the prolific Phil Coulter. It’s a collection of lush, tranquil and very thoughtful piano solos—with a little help from some heavy hitters like Moya Brennan, Billy Connolly, and one of our favorites, Finbar Furey. And I found myself thinking—this album would have been just the ticket on one of those cold, snowy nights. A splash of whiskey, the lights down low, a warm sweater—and Phil Coulter playing away quietly in the background.

Most people describe what Coulter does as New Age. It’s easy to dismiss the genre as just a bit of tinkly mood music. Sometimes, really, that’s all it is. Singularly unsatisfying. Anyway, it’s not my everyday, go-to genre, but—as on those blustery nights—nothing else that fills the bill quite as well.

“Echoes of Home” is understated. And it’s a recording of piano solos, so of course it’s not overly orchestrated. If you didn’t know what you were listening to, you’d think Phil Coulter wasn’t working very hard. But it takes a deft hand to take relatively complex musical themes and transform them into something light, airy, almost fragile—like spun sugar sculpture.

The album opens with “The Flower of Magherally,” and it sets the tone for everything that comes after it. (There are 15 tracks.) Coulter doesn’t get in the way of the tune. He sits back and lets the tune’s inherent sweetness stand on its own.

You might also appreciate Coulter’s take on “Minstrel Boy.” I play drums in an Irish pipe band, and if I never hear “Minstrel Boy” again, it will be too soon. I mostly liked Coulter’s version. “Minstrel Boy” is an anthem, one of the earliest patriotic songs. That approach has its place, but that’s about the only approach you ever hear. In Coulter’s case, “Minstrel Boy” becomes more of an air than an anthem. It’s a nice rendering, but ultimately manipulatively and obviously sentimental. Not so much spun sugar as saccharine.

Coulter redeems himself on several other tracks, including “David at the White Rock,” a traditional Welsh air. It’s a particularly evocative and inventive performance. There were moments where it was easy to believe you were listening to a Regency era piano sonata. (Think Jane Austen.) It’d the best, most fully realize piece on the album.

Now let’s talk about the second best—although, frankly, it could be a tie. Finbar Furey plays both low whistle and uilleann pipes (not at the same time), and in this moody little piece, Coulter takes a back seat and let’s Furey’s performance shine through.

Another collaboration didn’t work out as well. Moya Brennan’s performance on harp in “The Lass of Aughrim” seems like an afterthought. At the very end, she chimes in with a bit of gratuitous humming. She’s wasted on this track.

While we’re on the subject of tracks I didn’t much care for, let’s add “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face.” I don’t care that it’s not Celtic. But it matters very much that it adds nothing new. It’s a plodding, straightforward—too straightforward—rendition of a tune that most of us already know too well. As performed by Roberta Flack on her classic album “First Take,” it’s a classic. If you can’t do it better, don’t bother. (Michael Bolton, take note.)

Those are really the only false notes on what is otherwise, as the title suggests, a glorious collection.

The album ends with a spare and lovely “Farewell to Inishowen.” Coulter is accompanied by Paul Brady on low whistle. It’s a gentle, crystalline coda, more prayer than piano solo.

And if you’re not well and truly relaxed and completely at peace with the world by then, well, it might be time for another small whiskey.