Irish Ambassador Michael Collins and his wife, Marie, look at the remains of 18-year-old John Ruddy with Duffy's Cut Project managers Dr. William Watson and the Rev. Dr. Frank Watson.

He was 18 years old. He’d come to Pennsylvania from Inishowen, County Donegal, Ireland, on the ship, the John Stamp, with a box that contained all his earthly possessions. He had been hired by a railroad contractor named Phillip Duffy to help lay a stretch of railroad tracks (known as mile 59) through densely wooded hills and ravines near Malvern. Two months after he arrived, he was dead. No one alive today remembers John Ruddy. But 177 years after his death, his bones are finally telling his story.

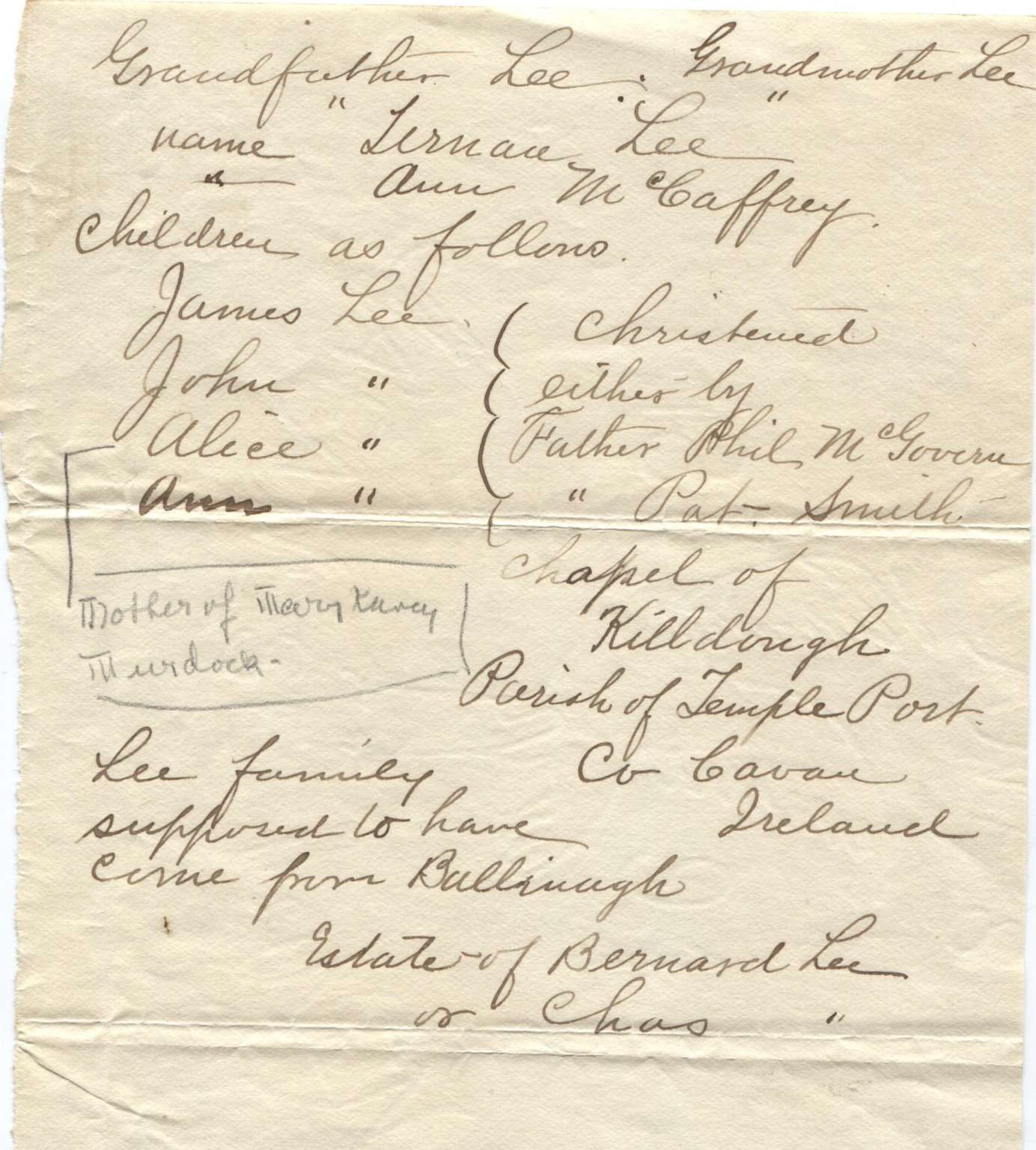

Ruddy was one of 57 Irish railroad workers who died in 1832 during a cholera epidemic. The men were not given medical help and some historians—notably William Watson, PhD, head of the history department at Immaculata University—suspected at least some of the men had been murdered to keep them from spreading the deadly disease. For the past six years, Watson, his twin brother, the Rev. Dr. Frank Watson, and a team of archeologists, historians, anthropologists, and students, have been sifting through the dirt at the site, now called Duffy’s Cut, where last March they found the first human remains.

The unfused skull with its zig-zag fault line told forensic anthropologists that the body was that of a teenager. When the Watsons looked at the manifest of the John Stamp, which brought many of the workers from Donegal, Derry, and Tyrone to Philadelphia, there was only one teenager—John Ruddy. The small indentation in the top of the skull and the larger hole in the forehead in which a rock had been wedged told the anthropologists that the young man had likely not died of cholera, but had been murdered, his body dumped from a sled into a shallow makeshift grave where he lay sprawled for almost two centuries. Pieces of the sled were found with him. Suddenly, their archeological dig had become a crime scene.

“For us, seeing this was completely heartbreaking,” says Frank Watson. But also exciting: They were witnessing an old folk legend come alive.

“This is an urban legend,” said Bill Watson, surveying the bones he had placed carefully on a table near his office last week, arranged so they could be viewed by Irish Ambassador Michael Collins and his wife, Marie, who were driving up from Washington just to see them.

This urban ghost story got its start 177 years ago with the first account of “ghosts dancing on their graves” reported by a local passing by the site. It continued, with some strange synchronicity, with Watson, who may have seen the ghosts of Duffy’s Cut himself—three strange neon figures not 10 feet from him, there and then gone. If there are ghosts, appearing to Watson was a serendipitous choice on their part. His Irish-American family has a connection to Duffy’s Cut.

The Watsons’ grandfather worked for the Pennsylvania Railroad. After his death, their grandmother entrusted to Frank some papers he’d left, detailing the initial efforts of the president of the railroad to have a memorial erected to the memory of the dead workers and then, inexplicably, his cover-up of the entire incident. After Bill’s ghostly sighting, Frank remembered the papers, and they began their tireless effort to uncover—both literally and figuratively—the truth about what happened to those 57 men.

It was also wise of Duffy’s Cut’s ghosts to bide their time. It was not only unlikely that anyone would have stumbled upon their mass grave (“It’s the valley that time forgot,” says Frank. “It’s useless for farming or raising animals. It’s a valley. It’s hard getting up and out of it”), but they chose to reveal themselves in the era of forensic science. John Ruddy’s teeth are “in good shape,” according to the forensic dentist who examined them. They are likely to yield a good sample of DNA that can be matched to living descendants.

The forensic scientists have already started to tell the story of the teenaged John Ruddy, says Frank Watson. “They know from his bones that he was heavily muscled and probably malnourished,” he says. “He stood about five-feet-six. We have his ear canal and they know that he had a lot of ear infections. He’s also missing a right front molar. It wasn’t knocked or taken out—it was never there.”

That last tiny fact stirred something in a family named Ruddy in Donegal. After reading about the findings, they contacted the Watsons to offer them their DNA for matching. “Many members of their family are also missing that right front molar,” he says.

The Watsons have no intention of keeping the bones for display, so if they’re able to find a DNA match, John Ruddy may finally find his way home again.