Here’s what soul crooner Gerald Levert, indie singer-songwriter Jim Boggia, jazz bass virtuoso Gerald Veasley and the inventive young Irish ensemble Solas have in common: John Anthony.

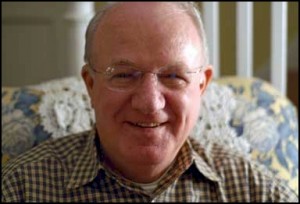

All are brilliant artists in their own right. But it is Anthony—audio engineer, producer and owner of Maja Audio Group in Society Hill—who helps give them their voice.

Anthony’s career path in music began one Sunday night in February, 1964, when a new band from England debuted on the Ed Sullivan Show. The drummer—a mop-haired guy with a memorable nose—made quite an impression on the kid from Newtown Square.

“It was Ringo,” says Anthony, a talented percussionist who lends a hand on many Solas recordings. “My dad had a big custom stereo that he built, and it had big speakers. The TV came through the stereo, which was revolutionary in those days. But I just watched that show with my head between the speakers. After that, that was pretty much it.”

Anthony went on to pound away in his fair share of bands, but his interest in just playing music always took a back seat to recording it. His early knack for extracting crisp, true sounds out of a performance eventually blossomed into a successful career.

How successful? In addition to the above, consider this eclectic artists’ roster: Grover Washington Jr., Omar Hakim, Karan Kasey, Dru Hill, Sara Hickman, Phil Lee, the Hangdogs, John Doyle, Liz Carroll, Sue Foley, Niall Vallely, Cathy Ryan, Susan McKeown, Jim Boggia, Eileen Ivers, Michael Manring, and the Dixie Hummingbirds. He has also worked on a number of films, including “The Brothers McMullen,” “Philadelphia,” “Beloved,” “Two Bits,” “The Siege,” “Barnyard,” “The Illusionist” and “Meteor Man.”

Anthony’s musical tastes are pretty clearly catholic, but his passion for Irish traditional music also is well-known. His skills have gained the attention of many Irish and Celtic recording artists, including piper Cillian Vallely, who is scheduled to begin recording at Maja in September.

We visited Anthony’s studios recently for a wide-ranging conversation about Irish music, and his long association with Solas, most recently on the new CD, “For Love and Laughter.”

Oh, yeah … and a bit about John Coltrane.

Q. How did you become so popular with Irish artists?

A. It’s all because of Seamus (Egan). I first worked with Seamus on a solo album of his, “When Juniper Sleeps.” I think that was in 1994.

Seamus had done his first solo record with my former partner Michael Aharon, who’s a producer and arranger. He (Aharon) was renting space at Sigma Sound Studios, and I was a staff engineer at Sigma. Michael was going to see if he could do the next record at Sigma, with me engineering. Seamus and I just kind of hit it off.

“Juniper” was really a great musical experience. To me, that’s always the best part of the project. The technical stuff, I either take for granted or I learn what I have to learn. But the music part of it is what has always interested me. I mean, I’m a musician, so the band dynamic and the music are what motivate me.

That project was just a total gas. It was the beginnings of the Solas organization. I mean, it was (guitarist) John Doyle, (accordion player) John Williams and (fiddler) Win Horan and Seamus and some other people like (drummer) Steve Holloway, who all went on to play with Solas. It was just a ton of fun. Seamus and I have stayed connected ever since.

Q. You’ve worked with other Irish artists since then. What do you think appeals to them?

A. I worked with Cillian and Niall (Vallely) on a record of theirs, I think, and also with Niall on Karan Casey’s next-to-last record. It just seemed a natural thing. I have a lot of enthusiasm for the music. I’m pretty good at editing, and I know where I am in the tunes. That’s of value to people. They’re not dealing with someone who doesn’t understand the structure of the tunes. Or if they say, “That bit there, it isn’t very good,” I know why. If it’s an ornament that didn’t quite happen … it just makes it much easier to communicate.

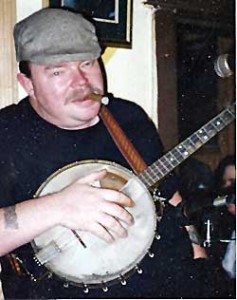

Q. What appeals to you about Irish music? It’s probably unavoidable that you approach it from a percussionist’s perspective. You play bodhran on many of the Solas recordings, including the 10th anniversary performance.

A. It occurred to me, after a couple of years, that I was doing records where the acoustic guitar took the place of the drums. The tracks were really big-sounding. They weren’t necessarily big-sounding from a rhythmic point of view. But it just kind of developed that way. It’s a really great sound, particularly when you’re working with John Doyle or Éamon McElholm. They have a great sound and a lot of the rhythmic underpinnings of a song are in their part. I just have a fascination with percussion in that music.

Q. I think I’ve noticed.

A. (Laughs.) Seamus is a really great bodhran player. He has a natural “feel.” The first time he played on a track, way back when, I thought … wow, what a great sound. And we sat down and he played me maybe five things where the bodhran was a really cool part of the arrangement, like some Donal Lunny stuff where he was playing with his hand … all different approaches to playing the instrument.

It can have so many different functions—tonally, rhythmically. It can be this big pillowy, low-end sort of thing, or it can be really cracking, like the first set of tunes on the new record.

Q. It can be more melodic, too.

A. Seamus really does that. He’s really sensitive to the notes and tones that the drum is playing, and bending the notes and crafting a part to the melody.

Even “Juniper,” going back, has really great percussion arrangements on it. As far back as that first project, there’s a slow piece—”Mick O’Connor’s,” I think—and that’s got at least four percussion parts on it. There’s Daryl Burgee, Ron Crawford and me, and we’re all playing percussion parts. The first set of slip jigs has a really great percussion arrangement. It’s a really crazy arrangement that John Doyle came up with on guitar that people think is in a completely odd time. The pattern of accents is really long—it’s like a four-bar pattern. And it doesn’t repeat again. So if you just pick it up somewhere in the middle, you have no idea what’s going on.”

Q. So you never played bodhran before working with Seamus?

A. No, I hadn’t. I had a fascination with Irish music, but I didn’t understand it well. But back in the early ’90s, I went to Ireland for the first time and I stayed out on the Aran Islands. There’s a little pub in the harbor where they have music all the time. I was sitting next to a guy who was playing bodhran, and it totally blew me away. I thought—I really want to learn how to do that! I’m still learning.

I’m pretty much a journeyman drummer-percussionist. I feel pretty lucky to have gotten to play with these people and not embarrass myself.

Q. When you were a kid in garage bands, what did you play?

A. We played all the early Cream and Jimi Hendrix, all the ’60s music. The first bands I was in played covers of “In My Room”—Beach Boy songs and all that crazy stuff.

Toward the end of high school I got into jazz. I was listening to blues music, and someone said to me, “If you like that you should listen to some John Coltrane. I had no idea what they were talking about. So I went to the record store and bought a John Coltrane record. I think it was “Ascension.” (1965) If you listen to it, it sounds like the band is tuning up for the whole first side. It’s pretty free. They play this one figure over and over again. They pass it all around, everybody plays it, and it just builds to this craziness.

I kept moving the needle, waiting for them to start playing something. And eventually I put the needle down on Freddy Hubbard’s trumpet solo. And it was like: Oh, my.

I waited a little while and went back and listened to it from the beginning. And all of a sudden, I just got what they were doing. So then I was totally into every jazz record I could get my hands on—Miles and Monk, Newport ’58.

Q. And here you are today recording Irish music.

A. You might think this is a digression, but the thing that totally blows me away about Irish music is the nuance and power of the ensemble playing. It’s the same as a really great Blue Note front line.

When Solas is playing live and you’re in the audience, it’s like a freight train. When they’re all just on, it’s just unbelievable. It doesn’t matter if they have a drummer or not. It’s the strength of the melody and the way that they phrase. Great Irish players are like that and they always have been. Irish music has that sensitivity. It’s not completely freely improvised the way jazz is, but there is definitely an element of interplay. It’s subtle and you have to be tuned into it. But it’s there for sure, and it really keeps the music alive.”