Seamus is going solo.

After 15 years, Seamus Kelleher, the lead guitarist for the ultra-popular Celtic rock band Blackthorn—their name in Irish means “sold out”—played his last gig with the guys he calls “my best friends.” It was last Saturday night at an Archbishop Ryan benefit (that was sold out, of course).

That doesn’t mean he’s not going to sit in occasionally. But after a near-death experience and launching his first solo CD a couple of years ago—two events that were nearly simultaneous—the Galway native says he wants to take a shot at “getting my own music heard by a wider audience.”

Kelleher is in his late 50s, a time when every birthday party reminds you that you’re closer to “last call.” But a few years ago, he got up close and personal with his own mortality. After a show, Kelleher tumbled down a steep staircase at the Kildare’s Pub in King of Prussia, fracturing his skull and suffering a traumatic brain injury. He was taken by helicopter to the University of Pennsylvania Trauma Center in critical condition. Miraculously, he came through with no residual effects though, he jokes, “that depends on who you talk to—some say yes, some say no.”

He’s also the father of four young children, ranging in age from 7 to 13; vice president of Philadelphia firm for which he travels; and in addition to his Blackthorn gigs he’s been soloing both here and in Ireland, playing his own brand of Celtic blues.

“I cherish my time with Blackthorn,” Kelleher told us this week. “I’m going to miss the guys so much, all the camaraderie and all the Blackthorn fans, but I feel an obligation to myself to make time to do this. I can only serve so many masters and I want to be 100 percent focused on what I’m doing. With all that going on, I didn’t have much left for the family. I believe that unless you have balance in your life you’re not going to be happy.”

After his debut album, “Four Cups of Coffee,” he began doing solo shows in Ireland (Monroe’s Live and The Crane in Galway, and Portmarnock Country Club in Dublin as well as Ulysses, a folk club in New York City, Puck in Doylestown, and lately, the Moose Lodge in Doylestown). He plays his own compositions and salts the evening’s playlist with covers of Jimi Hendrix, Jethro Tull, and Dylan. And comedy. There will always be funny stories and jokes.

“People come to my shows expecting me to be serious while immersed in my solos, but I can’t do that,” he says. “I’m too screwed up an individual to do that. I see the humor in things.”

Then he tells the story of when the paramedics were trying to take a history from him after he woke up in the chopper, post-staircase acrobatics. “I see lights flashing all around me and I thought to myself, is this me going to the other end?” he laughs.

They wanted to know if he had a family history of heart disease (both parents), and about his smoking (“only when I drink”), drinking (“five to six days a week, and on the weekends it could be 7-8 drinks looking at each other”), and whether he had high cholesterol (“Yep!”). “And I know they’re thinking, this guy’s dead. Then they asked me what I did. I told them, ‘I’m a musician.’ They looked at each other and started laughing. I know they were thinking, with that history, I should have been dead 10 years before I had that accident.

“Well there’s no better defense than humor,” says Kelleher, who cleaned up his act after that. “You can disarm the most miserable bastard in the world with a sense of humor and protect yourself from the bad times.”

That’s something he can share with his CD producer Pete Huttlinger. Kelleher has been in Nashville with Huttlinger, a renowned guitarist, recording some tracks for a new CD. Not long ago, Huttlinger, who is only in his 40s, suffered a stroke, leaving him paralyzed and speechless. “But he’s playing now with Darryl Hall and it will be a while but he’ll be back,” Kelleher says.

The new CD, he says, won’t be as eclectic as the first one, which reflected Kelleher’s many interests, from traditional Celtic music, to Southern blues, to the music by famed Irish rocker Rory Gallagher. “That first album had everything but the kitchen sink,” he laughs. “The new one will have a singer-songwriter feel to it. I’m putting together 10-11 songs that have a common thread. There will be a lot more continuity.” He expects it to debut in the spring.

Until then you can see and hear him again at Puck in Doylestown and on Friday, March 11, at the Moose Lodge in Doylestown. And maybe, occasionally, with the boys of Blackthorn. He’s not planning to stop the music any time soon.

“I’ve been been very blessed,” he says. “I’ve been in music 42 years professionally. Most musicians my age have long stopped doing it. I’m doing it more than ever and enjoying it more than ever. In last five years my playing has progressed much further than I ever imagined it would. And as long as I can see improvement, I’ll continue to play. Once that stops, it won’t be as interesting.”

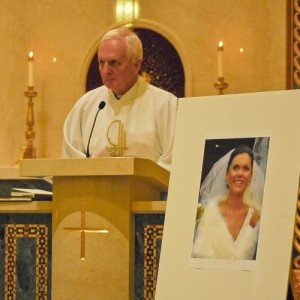

See photos by Patti Byrd of Kelleher’s swan song with Blackthorn.