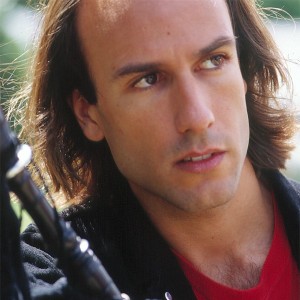

Carlos Núñez

It’s called the gaita, and Carlos Núñez is the widely acknowledged master of these haunting Galician bagpipes.

Galicia is a rugged province in Spain’s northwest, inhabited by Celts thousands of years ago. Núñez is clearly a product of his environment. Everything about his style of play seems like an echo of the landscape and the region’s ancient culture, and yet there is an inventive newness to it at the same time. It’s a sound that was never going to be confined to one far-flung corner of Spain—or even Spain as a whole.

It wasn’t long before his stellar talent came to the attention of The Chieftains, Ireland’s premier traditional music group. Núñez has collaborated with the Chieftains on several projects, including “The Long Black Veil,” “Santiago” and “San Patricio.” He has often been called the “seventh Chieftain.”

This gifted multi-instrumentalist—he’s about far more than pipes—made his first appearance in the United States in 1994, performing with the Chieftains at Carnegie Hall in the “Daltrey Sings Townshend” concert. Not long after that, Núñez skyrocketed to worldwide fame. His stunning two-CD compilation, “Discover,” highlights many of his collaborations, Chieftains and beyond. It’s a stunner.

Núñez is coming to Philadelphia’s World Cafe Live on Tuesday night—a bit smaller than Carnegie Hall. That said, it’s one of the best venues for live music in the city—if not the best.

We checked in with Núñez by e-mail a couple of days ago, to learn more about his life and his music. Here’s what he had to say.

I’m always interested in how musicians came to play the fiddle, the congas, the oboe, or whatever it is they play. When I talk to Irish musicians, often there’s a family background … or they grew up in a small town where it was expected that every kid would grow up to play something. How did you come to play the pipes? Was there a similar kind of musical background?

My great-grandfather was a musician, but he emigrated to Brazil and disappeared, so that nobody in the family continued that tradition until me. The pipes are the “national instrument” in Galicia, you know, the Celtic region in Northwest Spain. After Franco’s highly centralized dictatorship, democracy brought back the rich regional variety and I was raised at that time.

There are so many thousands of pipers now in Galicia that there were talks a few years ago to start a political party, if all pipers voted it, they’d get a good representation in parliament to defend the instrument!

A lot of kids grow up playing piano or flute, or whatever, and they’re good at it. It’s always something they can do, if only to play their “party piece.” For what seems like a handful of others, though, it becomes a passion. They simply cannot not play, and play well. How did gaita become your passion?

The first time I blew on the instrument I was 8, and I fainted. That’s love at first sight indeed! I haven’t stopped playing since. My teachers at school still remember me practising with my biro (pen) during their classes!

I’ll ask you the question everyone asks you. How is the gaita different from other pipes?

I often describe Scottish pipes as fire, Irish as water and Galician as land. I think our Galician gaita is kind of midway between the other two musically. The pipes have been in Galicia for a thousand years at least. Now Scottish scholars have the theory that they might have got the pipes from northern Spain via the “Atlantic corridor,” and the Irish have this medieval book, the “Book of Invasions,” that says basically about their own origin that a Galician king saw an emerald in the sea and sent people who populated the island. It seems DNA studies are now confirming that. Anyhow, it’s clear there are links and a mutual love, even if we speak different languages Celtic music unites us.

By the way, if yourself or any of the pipers in your band want to join us, you’ll be more than welcome, as many as we can accommodate on stage at World Cafe! We will have pipe bands playing with us in all the big festivals in this tour and we do play with pipe bands in Europe all the time. It’s fun and spectacular, big Celtic fiesta!

You’ve obviously become a worldwide phenomenon. (Understandably.) How do you account for that? Was it all the collaboration, especially with the Chieftains? Does something like that tend to open doors? (That’s not to suggest that your talent didn’t propel you forward in your career, collaborations or not.)

The Chieftains taught me that music has no frontiers, so that I have also collaborated with artists from many different countries and genres. My latest album is an anthology and you can find Jackson Browne, Ry Cooder, Linda Ronstadt, Los Lobos, Sinéad O’Connor, Waterboys’ Mike Scott, Laurie Anderson, Ryuichi Sakamoto, flamenco singer Carmen Linares, Irish accordionist Sharon Shannon, Scottish accordionist Phil Cunningham, flamenco guitarist Vicente Amigo, Brazilian star Carlinhos Brown, Early Music master Jordi Savall, Spanish soprano Montserrat Caballé, Buena Vista Social Club members Omara Portuondo, Compay Segundo and Cachaíto.

Talking about collaborations, I can’t forget our Philly friend Seamus Egan and Solas. Both bands toured together in Germany and we had a terrific time. Pity they are on tour too, now, so that we won’t meet them there.

You’ve been called the “seventh Chieftain.” If someone called me that, it pretty much would do me for life. How does that particular appellation strike you?

Well, it’s an amazing honor. We’ve played together so many times for well over 20 years. It’s not only that they opened the world to me when I was just a teenager, but we’ve kind of had parallel careers since. They play in virtually every album I’ve released and I do the same in theirs. Paddy Moloney was our special guest a few days ago in a concert in Brittany, and in this U.S. summer tour we have with us one of their current fiddlers and step dancers, Jon Pilatzke.

You’ve also been called the “Hendrix of pipes.” To me that means you’ve clearly taken the instrument beyond the bounds of its normal playing. As a musician, do you think you reach a point where you keep on playing things the way they’ve always been played, or you have to explore new frontiers? Did that happen to you?

You did have in Philadelphia a jazzman who kind of did the opposite trip towards the pipes: Rufus Harley!

In America many people say that my piping reminds them of Hendrix or electric guitar in general. In other countries they tell me I play “Celtic music with Spanish passion.” I think it’s the energy, especially live. I do explore the instrument too, I’ve had amazing experiences playing with flamenco guitarists or Brazilian percussionists, but I usually don’t make experiments just for the sake of it, I try always to be very respectful to tradition exploring the amazing connections and possibilities that it offers if you go into its deepest roots.

As you look back on your career, does it seem to you the way it seems to the rest of us? That is to say, you’ve been successful perhaps beyond your wildest dreams? And you’re pretty young, so you have a long career ahead of you. Is there a kind of roadmap in your head as to where you want to go next, musically, or do you take it as it comes?

I always feel I’m just starting. Still so many projects and dreams! When we did this anthology for Sony masterworks, “Discover”, I was surprised myself of how much we had done, that I had forgotten! Now I’m so happy for instance to be back in America touring with my own band, as I did for years with The Chieftains, I’m really enjoying it and so does the audience as far as I can see. So, see you all in Philly at World Cafe next Tuesday. Let’s make Celtic fiesta !

Concert details here: http://tickets.worldcafelive.com/event/290839-carlos-nunez-philadelphia/