A hole in the back of this skull is being carefully examined.

On April 13, 1832, the John Stamp set sail from Ireland bound for Philadelphia. Among the passengers were a group of young laborers, men between the ages of 18 and 30, set to work upon a track of railroad known as mile 59 in what is now Malvern, PA. Within two months of their June 23rd arrival, they would all be dead, buried anonymously and without ceremony, in a mass grave in Duffy’s Cut.

For over 170 years, these men, 57 in all, were lost to history.

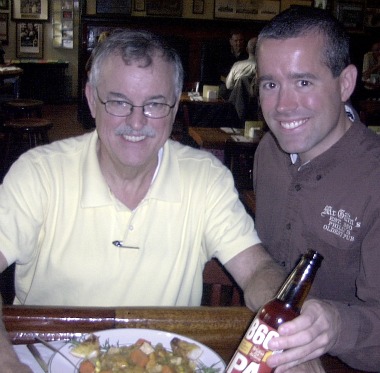

Local archeologists Frank and Bill Watson, along with their dedicated team, have found them.

It’s a still unfolding tale ready-made for “History’s Mysteries:” Irish immigrants, prejudice, cholera, murder, cover-ups, secret files, ghosts and 21st century technology.

My visit to the Duffy’s Cut site came just a little over a month after the discovery of two more bodies, identified as Skeleton #6 and Skeleton #7. This is exciting stuff, with #6 almost in its entirety, only the right arm and ribs lost to decay. They know the man was very tall for his day, about 5’8, and around 30 years of age. His wisdom tooth, which was intact, will be sent off for DNA testing.

Skeleton #7, on the other hand, was a much shorter man, around 5’2. But his skull tells a very big story: the crack shows he was hit on the head, and there’s a hole in the back that is being examined very carefully by Janet Monge, Adjunct Associate Professor in the University of Pennsylvania’s Archeology Department. It’s presumed to be a bullet hole.

What has become increasingly clear is that these Irish immigrants did not all die from the cholera that attacked them; at least some of them were murdered because of fears they would spread the disease, and because they were considered dispensable.

Cholera in the 1830’s was a source of mass hysteria in communities. Its cause was unknown then, but it would have been communicated by contaminated drinking water. It killed about 30-40% of its victims, so the 100% mortality rate at Duffy’s Cut has always been suspect.

The surrounding community would have been afraid of the outbreak spreading from the railroad workers to the general population, and the men would have been quarantined to their site. They would have been turned away from any homes they approached for help.

However, it’s known that they did receive care from a local blacksmith, tentatively identified as MalachI Harris, and four nuns from The Sisters of Charity.

Seven men attempted to escape from the site, but were hunted down by The East Whiteland Horse Company, a group of farmers acting as local vigilantes whose mission was “to track down horse thieves and other breakers of the law.” Those seven men are the only ones to have been provided coffins before their burials; coffins that have mostly disintegrated due to time and the particular composition of the local soil.

“When we first started the dig at the site, there was no sign of life here. Nothing. And now, living creatures are coming back,” Frank Watson, who has a Ph.D. in historical theology, said as we watched a beautiful blue butterfly hovering for several minutes, flitting from one place to another almost as a guide to what discovery will be made next.

It was the file that Frank inherited from his grandfather, Joseph F. Tripician, that was the key to discovering these men. “Our grandfather was the personal assistant to four different presidents at what was The Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad. He was an immigrant from Sicily, who worked his way up.“

Since the 1830’s folktales and ghost stories had circulated locally about the deaths of the railroad workers. One tale, recorded in an area newspaper in the 1880’s, told of a man walking by Duffy’s Cut in the fall of 1832 (on the way home from the pub), who saw Irishmen dancing on graves. In 1909, there was a railroad marker placed there, but without details.

In other words, an urban legend with no corroborating evidence.

Except for the detailed documents that were hidden away in the secret file kept by each of the presidents of the P&C Railroad, amassed and passed down over a period of 100 plus years. The file began with information from the time of Philip Duffy, the man who was charged with the building of the railroad, and the man who was cited in an 1829 issue of the “American Republic” as “prosecuting his Herculean task with a sturdy looking band of the sons of Erin.”

These documents revealed beyond a shadow of a doubt the existence of a mass unmarked grave along mile 59.

The last president that Tripician worked for was Martin W. Clement, who died in 1966. It was Clement who had the 1909 marker erected at the site, and who actively worked to acquire a lot of the information stored in the file. In 1968, when the railroad was bought out two years after Clement‘s death, Tripician ended up with the file. And after his death, his grandson Frank Watson inherited it.

In 2002, Frank and his brother Bill, who is Professor and Chair of History at Immaculata University, were finally sorting through their grandfather’s papers, and Frank pulled out the file. Reading through it, they were struck by what they found there, including the account of the dancing Irish ghosts; two years before, Bill and his piping buddy Thomas Conner had experienced the same phenomenon on the campus of Immaculata College. The college is located about one mile west of Duffy’s Cut.

That was the start of The Project. They began assembling a team that now includes geophysicist Timothy Bechtel and forensic dentist Dr. Matt Patterson. Dr. Janet Monge and Samantha Cox from The University of Pennsylvania are key to “cracking the whip in terms of archaeology.” Immaculata College has supported them, even providing the insurance and a grant this summer that has paid for new tools and food for the volunteer crew. Norman Goodman, a former deputy coroner from Chester County, has pledged to help obtain death certificates for the men. East Whiteland Township, as well as the residents of the development surrounding Duffy’s Cut, have all been cooperative. Former students like Robert Frank, Patrick Barry (Frank and Barry found the first bone) and Earl Schandelmier have stayed with the project beyond graduation from Immaculata.

As the momentum has built over the past few years, following the initial discovery of artifacts like a Derry pipe stem and a bowl marked with a harp flag and the words “Flag of Ireland,” the story has garnered international attention. Tile Films in Dublin began filming the dig, and when the documentary aired on RTE in 2007, it was one of the highest rated programs in Irish history. They sold the rights to the Smithsonian for broadcast in the U.S., and continue to film as the story unfolds. They were onsite when Skeletons #6 & #7 were uncovered.

“The story of Duffy’s Cut has gathered a huge amount of interest in Ireland,“ Frank explained. “We’ve done a lot of radio interviews. “

In fact, it was because of one of the radio interviews that the body of John Ruddy was able to be positively identified. He was the first man discovered, in March of 2009, and with a very distinctive dental characteristic: he was missing his right front molar. Missing in the sense that he never had one. After hearing about the genetic quirk on the radio, members of the Ruddy family still living in County Donegal (where the ship’s manifesto revealed John had been from) contacted the Watsons and told them that many members of their family are also missing their right front molar. And, they offered to pay for their DNA testing in order to provide a definitive match.

The fascination that Duffy’s Cut holds is in large part due to the sense of a great injustice finally being righted. According to information revealed in the file, the extreme lengths that the railroad company went to in suppressing the story continued for well over a century. In 1927, local reporter Royal Shunk sent a letter to a clerk at the railroad thanking him for the loan of a file in conjunction with an article Shunk was writing for a local paper. The story never appeared, most likely suppressed when higher-ups got wind of it.

A diary kept by the daughter of local militiaman and 1832 local cholera victim, Lt. William Ogden, was noted in the file as having information pertaining to the death of the men. The diary disappeared sometime after the death of the last sister in 1913.

As recently as four years ago, an unofficial and unauthorized visitor to the site tried to convince the Watsons that they didn’t have the proper authorization to continue with their excavation. Completely untrue, as the brothers have gone to extraordinary lengths to insure that every i is dotted, and every t is crossed.

So, when Christy Moore recorded the song “Duffy’s Cut” written by Wally Page and Tony Boylan, on his 2009 album, “Listen,” Frank Watson sent him a message telling him how much the song meant.

The men, who were once victims of the kind of injustice that history is peppered with, are now the stuff of legend. It’s been a long time coming, but it’s an amends that could never have been made without the advances in technology available today, as well as the unique set of circumstances that put The Duffy’s Cut file in the hands of the Watson Brothers.

As Bill Watson said, “It’s like an echo through time. There was something so right about removing those men. They weren’t meant to die here.”