The Watson brothers, Bill and Frank, show recovered bones to former Irish Ambassador Michael Collins and his wife, Marie.

Every day, Amtrak trains traveling the Keystone Corridor near Philadelphia’s Main Line rumble over the mass grave of 50 Irish immigrants who died—or were killed—while working on this stretch of rail line, the oldest in the system, known as Duffy’s Cut.

The men—from Donegal, Derry and Tyrone—and seven others had been brought to the United States by a man named Phillip Duffy to finish this wooded stretch of rail near Malvern in the fall of 1832. In less than two months, they were all dead, some as the result the cholera pandemic, others as the result of violence.

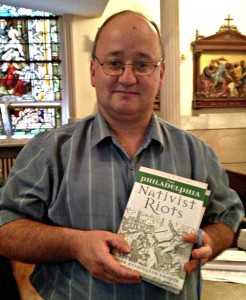

An Irish railway worker erected a small memorial to them, which was replaced by a stone enclosure in 2004. But their memory was shrouded in myth until 2009, more than 100 years after their deaths, when Immaculata history professor William Watson, his twin brother Frank, colleague John Ahtes, former student, Earl Schandlemeier, and a team of students discovered the first human bones—two skulls, six teeth, and 80 other bones. In all, the remains of seven bodies—six men and one woman—were recovered. Forensic testing suggested that some may not have died of cholera, but were killed, in all likelihood by local vigilantes fueled not only by anti-Catholic bigotry but fear that the workers would infect the rest of the community with cholera, which is normally transmitted through water and food.

Six of the seven recovered victims were re-buried in a 2012 ceremony in West Laurel Hill Cemetery in Bala Cynwyd. One, tentatively identified through a genetic dental anomaly as John Ruddy, a 19-year-old from the Inishowen Peninsula in Donegal, was buried in a cemetery plot in Ardara, on the west coast of Donegal, donated by Vincent Gallagher, president of the Commodore Barry Society of Philadelphia. The Watson brothers arranged for a Catholic burial, which they attended.

But 50 men remain unaccounted for. Except for the tracings on ground-penetrating radar scans that appear to show air rather than dirt in an area beneath the tracks which may indicate where the earth shifted as bodies decomposed. “We had planned to just have a memorial at the wall where the bodies were buried, but a number of people working on our behalf convinced Amtrak to let us dig for them,” says Dr. Bill Watson, who is eager, he says, “to end the story of Duffy’s Cut.”

The problem is that unearthing the long-dead Irish immigrants will be expensive. Not the work itself. An Irish immigrant named Joe Devoy, founder of ARA Construction in Lancaster (as well as the music venue Tellus 360) is donating the equipment and labor—roughly $30,000 worth—to do the earthmoving over the 40 days of the project. But Amtrak is charging upwards of $15,000 in fees, largely in labor costs for engineers to review the exhumation plans and monitor the work, which must be paid upfront before any work begins. Watson and his small nonprofit organization don’t have it.

That’s why a group from Philadelphia’s Irish community, including Irish Immigration Center Executive Director Siobhan Lyons, Irish Network Philadelphia President Bethanne Killian, Irish Memorial Board President Kathy McGee Burns, and musician Gerry Timlin, are launching a fundraising campaign, the centerpiece of which is a musical fundraiser on Sunday, June 15, at Twentieth Century Club84 S. Lansdowne Avenue in Lansdowne.

Along with Timlin, performers will include John Byrne, Paraic Keane, Rosaleen McGill, Gabriel Donohue, Marin Makins, Donie Carroll, Mary Malone, Den Vykopal and others. Makins and Donohue perform their version of the song, “Duffy’s Cut” on irishphiladelphia.com’s CD, “Ceili Drive: The Music of Irish Philadelphia.” The event, which includes food and drink and raffles, costs $25. Tickets are available online. S

ponsorships are also available via the Duffy’s Cut website. Among the current sponsors: ARA Construction (Joe Devoy), Kris Higgins, The Friendly Sons of St. Patrick, Bringhurst Funeral Home and West Laurel Cemetery, Wilbraham, Lawler, and Buba, The Irish Memorial, The Irish American Business Chamber and Network, the Philadelphia Ceili Group, The Delaware Valley Irish Hall of Fame, Mid-Ulster Construction, Infrastructure Solution Services, Kathy McGee Burns, AOH Notre Dame Division and the Joseph E. Montgomery AOH Div. 65, www.irishphiladelphia.com, “Come West Along the Road” Irish radio show on AM Radio 800 WTMR, Lougros Point Landscaping, The Vincent Gallagher Radio Show on WTMR, Curragh LLC Newbridge Silerware, Magie O’Neill’s Irish Pub and Restaurant, Con Murphy’s Irish Pub, The Plough and the Stars, Tir Na Nog Bar and Grill, Conrad O’Brien, and Brian Mengini Photography.

Watson doesn’t know eactly why the 50 men were buried apart from their seven co-workers (who included a woman who tended to the men’s laundry). “The theory is that the bodies were moved in 1870 by a man named Patrick Doyle who was a railroad gang leader when they were found during an expansion of the tracks to accommodate locomotives and larger vehicles,” he explains.

Doyle may have put a fence near the graves, which was replaced in the early 1900s with a granite block enclosure by a mid-level railway official named Martin Clement. His superiors wouldn’t permit him to erect a plaque explaining the significance of the enclosure.

Clement eventually became president of the railroad. His assistant was the Watson brothers’ grandfather, who kept the file on the Duffy’s Cut incident which the two men discovered in 2002 when going through some family papers. It was only then that they realized that there had been 57 dead immigrants buried in and around Track Mile 59. Only seven were ever mentioned. Apparently, between the time Clement worked in the railroad’s middle management till he became its president, he had become convinced of the need to keep the matter secret.

“And of course we now know why—there were murders, and fingers would have pointed at the railroad,” says Watson. A diary kept by a local woman of the time mentioned the cholera epidemic, “but that disappeared,” says Watson. “Probably because it would have embarrassed the people who were leaders in the community.”

Janet Monge, a physical anthropologist and curator of the The University of Pennsylvania Museum, plans to examine the bones recovered from this second mass grave, just as she did the other seven, though Watson says she may not be able to be as accurate.

“We may not know as much about these bodies as we do the others because Janet thinks there may be a greater range of decomposition—they may have decomposed at a faster rate than the others,” he says. Watson is anxious to say goodbye to the Duffy’s Cut site, but not because he’s tired of being a history professor doing the work of archeologist. There’s more archeology in his future. Sleuthing has turned up several other nearby sites, including one in Spring City, where Irish immigrants were buried, victims of the same cholera epidemic—and possibly, anti-Catholic violence—as the Duffy’s Cut victims. “And we can’t go there until we’re finished with Duffy’s Cut,” says Watson.