Frank and Bill Watson are joined by a third piper at the gravesite in Ardara, Donegal. Photo courtesy of Donegal News.

By Harry Walsh in Ardara

Reprinted with permission of the Donegal News

DONEGAL man John Ruddy was buried in Ardara on Saturday afternoon, 181 years after he was believed to have been murdered at Duffy’s Cut, 20 miles west of Philadelphia.

Ruddy, from Inishowen,was among a group of 57 Irish labourers were who sailed from Derry on the John Stamp in June 1832. Within five weeks of arriving, all had perished.

On Saturday afternoon, he was accorded honours denied during his short, cruel life as his remains were interred following a poignant burial ceremony conducted by Canon Austin Laverty, Parish Priest, Ardara.

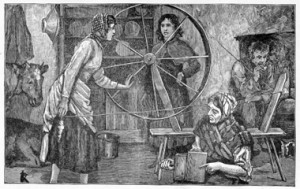

The casket was carried to its final resting place by Earl Schandelmeier, a Historian at Immaculata University, which was the driving force behind the Duffy’s Cut project, accompanied by three pipers in kilts. They were closely followed by Sadie Ruddy, who lives in Portnoo, and her first cousins James and Bernard Ruddy from Quigley’s Point, all three of whom are direct descendants of the deceased.

Canon Laverty told those assembled that “this brings a form of closure to a sad and shameful chapter of American history and re-enforced how desperate times were in this country at the beginning of the nineteenth century.”

Looking out across the graveyard towards Loughros Bay and the Atlantic Ocean beyond, Canon Laverty noted that Slieve Tooey – visible in the distance – was possibly the last piece of Ireland that Mr Ruddy and those who left Derry in 1832 saw through the mists of their tears.

“In a strange way it’s appropriate that his mortal remains are laid here to rest in his native county,” Canon Laverty said.

Prof William Watson of the history department at Immaculata who spearheaded the research and excavation with his twin brother Frank Watson were then joined be fellow piper Tom Connors to play Amazing Grace.

Speaking afterwards a clearly emotional Mr Schandelmeier said that he had been overwhelmed by the whole project.

“This has gone from being something which was on a piece of paper, and time spent looking through the archives, to finding a guy whom we are able to bring back to his homeland today.

“Lots of things happened to allow that to happen – it was almost synchronisity. Things were lined up and it was as if he was almost delivered to us.

“The body we excavated had a one in a million anomaly. There are not a million Ruddys and there are not a million people in Donegal, and here’s a Ruddy and he has it and two of his aunts have it and they also have a story in the family of a guy coming over to the US in the 1830s, working on the rail road and vanishing. What are the odds of that? How could it not be him? It’s been truly miraculous and, as a result, today was incredibly moving,” he said.

“This is history which has been brought to life. It’s not just black and white any more. He has a face, teeth, we’ve uncovered the instruments he ate with – he’s a human being.

“Sad events like this happen every day all over the world. People die unnecessarily – their memories are lost and no one cares. It’s great to be able to give him some dignity – if it’s 181 years ago or if it was yesterday,” he said.

Philadelphia-Columbus railway

The story starts in 1828, when Irishman Philip Duffy won a contract to build Mile 59 of the Philadelphia-Columbus railway.

Mr Duffy enlisted “a sturdy looking band of the sons of Erin”, according to an 1829 newspaper article. The men moved heavy clay, stones and shale from the top of a hill to an adjacent valley, hence the name Duffy’s Cut. They were poor, Irish-speaking Catholics who would have been paid “$10 to $15 a month, with a miserable lodging, and a large allowance for whiskey” according to a British historian of the time.

Cholera broke out and the workers’ camp was quarantined. Some escaped but returned because the surrounding affluent Scotch-Irish population refused to help them.

“Of all the places in the world, this was the worst place for them to be,” Prof Watson explained. “They were expendable. Because they were recently arrived Irishmen, they were assumed to be the cause of the epidemic. It was anti-Catholic, anti-Irish prejudice; white-on-white racism.”

Prof Watson learned of the story in 2002, when he found a secret report that had been kept by his grandfather, an assistant to the president of the Pennsylvania Rail road.

In 2005, excavations near the Amtrak line unearthed old glass buttons, crockery and a clay pipe stamped with an Irish harp – “the oldest example of Irish nationalism in North America”, says Prof Watson.

Four more years passed, and the project enlisted the help of a geologist armed with a ground-penetrating radar. The first remains, those of John Ruddy, were discovered.

Mr Ruddy never grew an upper right first molar, a rare genetic defect. When the find was reported in Ireland, two dozen members of the Ruddy family contacted Watson. One of them, William Ruddy, travelled to Pennsylvania to give a DNA sample.

Prof Watson says “hundreds and hundreds, probably thousands” of Irishmen died building US rail roads and canals.

“The doors are opening slowly” to excavate the bones of the other 51 victims from Amtrak and private property at Duffy’s Cut.

Immaculata University is establishing an institute to explore at least six more mass graves in Pennsylvania and neighbouring states.

“The industrial revolution was made by Irishmen,” says Prof Watson. “Nobody talks about the toll it took on them. We’re looking at the seamy underside of the industrial revolution.”

See the story as it originally appeared in The Donegal News.

Special thanks to Sean Feeny of The Donegal News.