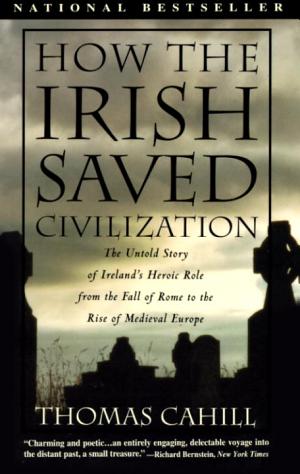

There’s nothing like immersing yourself in a good Irish book to get into the spirit of the month. While it’s all music, dancing, parades, and Irish potatoes everywhere you look, storytelling is quintessentially Irish, arguably the oldest form of entertainment in any culture. If you count history in there, it’s how the Irish saved civilization, according to the book of the same name by Thomas Cahill.

There’ll be no touting of “the 10 best Irish books ever” here. There are hundreds of books that are near and dear to people who love Irish literature and culture. We know. We asked the members of our Irish Philadelphia Facebook group to recommend their favorites, and we added our own, plus some on our “to read” list, to a master list we’re keeping.

Starting this week, we’ll be sharing some with you every Friday. If you click on the book title, it will take you to Good Reads, a book website, where you can see how others rated the book and find links to take you to websites where you can buy it.

Feel free to include your favorite book or books in the comments section at the end of the story and come back every week for more reading material.

Let us know if you might be interested in forming an Irish reading group. It’s something we’re considering since we not only love to read, we’re writers and one of us is a librarian. Books rule!

Fiction

The Agnes Brown Trilogy (The Mammy, The Chislellers, The Granny) by Brendan O’Carroll

Comedian Brendan Carroll not only played the foul-mouthed Agnes Brown, matriarch of a fatherless brood, on television (Mrs. Brown’s Boys), he wrote a series of semi-autobiographical novels about the very funny, charming, and irascible Brown family. Angelica Huston starred as Agnes in the movie. We still prefer Brendan. (This link takes you to a clip of an episode–strong language/sexual situations alert.)

Circle of Friends by Maeve Binchy

Set in Ireland in 1950, the story follows the unlikely friendship between 10-year-old overweight only child Benny (Bernadette) and skinny orphan Eve who is being raised by nun in a convent where she was placed by her mother’s wealthy family. The narrative takes them to university, through various romances and betrayals. Binchy was a prolific writer whose novels are wildly popular; some, like this one, have been made into films.

Dubliners by James Joyce

A collection of fifteen short stories by James Joyce depicts life among middle-class Irish living in and around Dublin in the early years of the 20th century, when Irish nationalism peaked. Some of the characters in these stories later appear in Joyce’s most famous novel, Ulysses. Use this book as your entree into that one, which may be a more difficult read.

Ireland by Frank Delaney

The last of the great Irish storytellers, or seanachies, arrives at the home of 9-year-old Ronan O’Mara in 1951 but is run out by Ronan’s mother, who thinks the stories he tells, handed down in Ireland’s great oral storytelling tradition, are blasphemous. Ronan is smitten and tracks down the storyteller who presents him with what one reviewer called “a kind of Irish book of Genesis,” starting with the construction of Newgrange in 5000 BC.

Let the Great World Spin by Colum McCann

This novel set in New York merges the lives of a seemingly disparate group of people, including two men from Ireland—Corrigan, a monk working in the slums, a his brother Ciaran , newly arrived. The plot revolves around the real tightrope walk of Phillipe Petit between the Twin Towers in 1974 and the fictional trial of a prostitute. The Twin Towers serve as a metaphor for man’s uncanny ability to find meaning in life.

The Barrytown Trilogy by Roddy Doyle

You saw the movies—The Commitments, The Snapper, and the Van—now read the books that chronicle the lives of the Rabbitte family of Dublin.

Nonfiction

Angela’s Ashes by Frank McCourt

This Pulitzer Prize-winning 1996 memoir by the Frank McCourt covers his gritty, impoverished childhood and early adulthood in both Limerick, Ireland and New York. The son of an alcoholic father and resourceful, loving mother (Angela), McCourt tells his story of tragedy and, eventual, redemption with skill and humor.

McCarthy’s Bar by Pete McCarthy

Pete McCarthy grew up in England, but spent time with his mother’s family in Ireland. His book began with a single premise, “Never pass a bar with your name on it,” and he doesn’t.

Paddy’s Lament by Thomas Gallagher

Written in 1962 by a second generation American of Irish descent, Paddy’s Lament is an eye opening history of what’s erroneously called “The Potato Famine”—the failure of one crop doesn’t constitute a famine—and the difficulties faced by the Irish both in Ireland and in emigrating.

How The Irish Saved Civilization by Thomas Cahill

How did they do it? According to this entertaining book, by preserving the great thoughts of other cultures in excruciating detail, Book of Kells style.

1916: The Easter Rising by Tim Pat Coogan

The 100th anniversary of this landmark of Irish freedom is next year. Bone up now with this book by this controversial journalist and historical writer, who is former editor of the Irish Press newspaper.

Mystery

In the Woods by Tana French

This is the first in a series of mystery novels by French, who is American, that uses the Dublin Murder Squad as its backdrop. This plot of this Edgar Award winner for best first novel focuses on the murder of a 12-year-old girl and the two detectives assigned to the case.

Haunted Ground by Erin Hart

Hart specializes in bog bodies—the dead whose remains are preserved in Ireland’s turf lands. Her protagonists in this first of three novels are Irish archaeologist Cormac Maguire and American pathologist Nora Gavin who work together to solve the mystery of a woman with red hair whose body is found by farmers cutting turf. Read our interview with author Erin Hart.

Inishowen by Joseph O’Connor

Police Inspector Martin Aitken thinks his life is a mess—he’s divorced, his career’s on the skids—until he meets an American woman who has collapsed on a Dublin street. Ellen is an Irish adoptee, taken out of Ireland as a baby and adopted by an American couple. She’s dying, and looking for her natural mother. Their roads and that of a successful New York plastic surgeon meet and take the three to Inishowen, County Donegal, Ireland’s most northerly point.

The Sister Fidelma Mysteries by Peter Tremayne

Writing under one of many pseudonyms, Peter Berresford Ellis has spun more than a dozen tales of the fifth century noblewoman turned lawyer turned nun and her companion (later husband) Eadulf who solve mysteries while revealing the history of Ireland and Europe of the time and, in particular, the unique Irish or Brehon system of law, which was fairly modern in its outlook. The books are so popular they’ve spawned the Sister Fidelma Society where you can learn more about them.