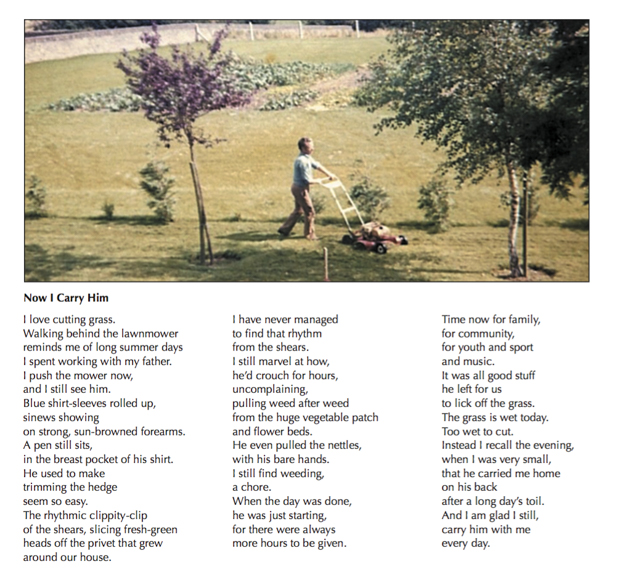

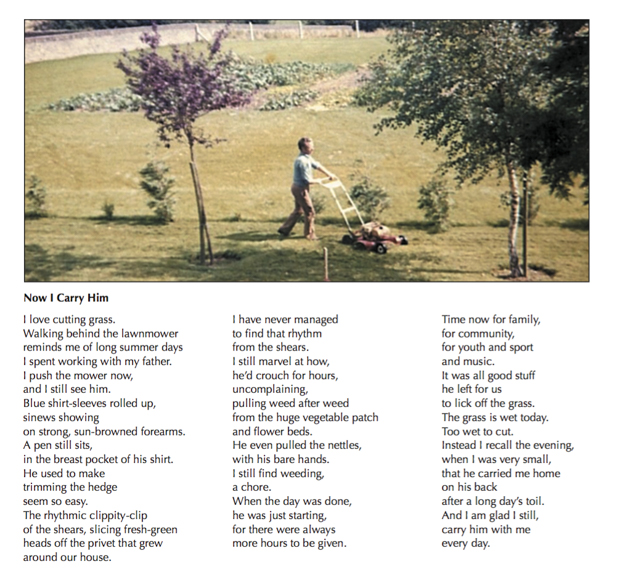

John Feeley, left, with Joyce’s guitar, and Fran O’Rourke.

Had they consulted a marketing wizard before naming their CD, “JoyceSong: The Irish Songs of James Joyce,” singer Fran O’Rourke and classical guitarist John Feeley might called it “James Joyce’s Greatest Hits: A Soundtrack from the Collected Works of Ireland’s Foremost Writer.”

If you’ve casually read The Dubliners, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Finnigan’s Wake, or Ulysses, you may have missed Joyce’s musical references, though they’re prominent symbols throughout his body of work.

But Dublin’s favorite son was a singer and guitarist, the son of a singer and guitarist, who was leaning toward a musical career before he was captured by the lyricism and harmonies of language. In fact, he once shared a stage with renowned Irish tenor John McCormack. And his wife Nora, the inspiration for many of his female characters, once bitingly remarked, “Jim should have stuck to singing.”

Though writing took primacy over a career on the stage, Joyce remained captive to song—from Wagnerian opera to the Irish traditional music he learned as a boy, what O’Rourke, professor of philosophy at University College, Dublin, calls “the music of the people.”

O’Rourke and Feeley, who is considered Ireland’s leading classical guitarist, will be performing Joyce’s greatest hits on Saturday at 4 PM at the Rosenbach Museum and Library at 2008-2010 Delancey Place in Philadelphia, as part of the Rosebach’s annual “Bloomsday” festivities, marking the fine June day (June 16) Leopold Bloom wandered the streets of Dublin in the 900 pages of Ulysses. The Rosenbach houses one of Joyce’s handwritten copies of the book.

O’Rourke, whose first “artistic connection” with Joyce came when he was 14 and sang a traditional song on Irish television, “a line of which occurs in Finnegan’s Wake,” revisited Joyce as a scholar because of their mutual interest in philosophy. He was delighted—and remains delighted—to also find the music there.

“The story, ‘The Dead,’ from The Dubliners, almost the entire tenor of that story, the ‘mood music’ of that story, comes from the Irish traditional song, ‘The Lass of Aughrim,’” said O’Rourke, whom I met, with Feeley, this week in the lobby of their hotel in Center City. “The story is so sparse, so beautiful, not a word out of place. The atmosphere of the story was inspired by that song.”

It is the recreation of an Irish family party attended by one of the main characters, Gabriel, and his wife who, listening to someone singing the lachrymose song about a lover’s death at the party, finds her mind wandering back to her teenaged sweetheart, Michael Furey, who died of a cold after coming to visit her. When the two return to their hotel after the party, Gabriel faces the truth that he is not his wife’s first—nor greatest—love. You can see and hear Feeley and O’Rourke performing “The Lass of Aughrim,” with Feeley playing Joyce’s own guitar, here.

“Ulysses is composed of 18 episodes and in each episode a different art dominates,” says O’Rourke. “The episode called ‘Sirens’ is the counterpart of the sirens who bewitched Homer’s sailors in ‘The Odyssey,’ [the Greek story of Ulysses’s travels]. The episode takes place in a hotel where people are singing two songs. One is “The Croppy Boy” and the other is “The Last Rose of Summer,” by Thomas Moore. Practically every word is quoted or parodied in that episode.’

Those songs are part of the program the two musicians are bringing to the Rosenbach on Saturday, then to the Irish Embassy in Washington and Solas Nua, a DC nonprofit dedicated to the promotion of Irish arts, next week to honor both Joyce and Irish poet William Butler Yeats, whose 150th birthday is Saturday, June 13. Their tour is sponsored by Culture Ireland (Cultur Eireann), which provides funding for the presentation of Irish arts internationally, and, in Philadelphia, by the Irish Immigration Center.

One treat you can hear on their CD but not in concert is Feeley’s rendition of “Carolan’s Farewell” on Joyce’s guitar, which is now owned by the Irish Tourist Board and housed in the Joyce Tower Museum since 1966. In 2012, O’Rourke helped fund the guitar’s restoration (along, he says, with a “generous donation” from New Yorker poetry editor Paul Muldoon) by UK luthier Gary Southwell.

It went from playable to barely playable, but Feeley was able to coax out the tune. “It was in very bad shape to begin with,” says Feeley. “Gary Southwell dated it to 1830, which means it was an old guitar when Joyce got it. It’s not a top guitar which you can see the way the finger board is worn down. As a guitar, it’s not particularly great, and that’s being generous, but it’s actually a sweet instrument, with a small sound. It also has a small problem. The turning pegs are irregular. They’ve worn down quite a bit so it tunes in installments.”

But, he says, that didn’t diminish the thrill of playing it. “It’s amazing,” says Feeley. “You feel you’re playing a piece of history.”

Because they’re only scheduled to play for an hour on Saturday, you also may miss the highly entertaining banter between the two men. How did they meet, I asked them.

“I had John’s first album,” said O’Rourke.

“At least he had some taste,” Feeley remarked with a glint in his eye.

“That first album was fabulous. Happily one day we met on the street and said hello,” O’Rourke continued. “What was your first album anyway?” he asked, turning to Feeley.

“It was just called ‘John Feeley,’ actually,” said Feeley, returning the gaze. “It came out in 1985. I was two years of age.”

And so, I asked, are you two friends?

“Oh no. No, no,” said Feeley, barely surpressing a laugh.

“Intermittently,” deadpanned O’Rourke. “We have a lot in common.”

“Yes,” said Feeley. “We live in the same country.”

You don’t need to be a Joyce scholar—or even a fan—to enjoy the JoyceSong concert, but a love of Irish traditional music helps. Purists may be thrilled to hear O’Rourke’s and Feeley’s rendition of “Down by the Salley Gardens”—one of Yeats’ compositions– which is historically accurate. That is, it may not be the tune you’ve heard or played—it’s been done by everyone from John McCormack to the Everly Brothers, the Clancys and Black 47. But it’s probably the one Joyce sang in his sweet though thin tenor voice.

You have a second chance to hear John Feeley this weekend. He’ll be playing classical guitar the the Settlement Music School, 416 Queen Street in Philadelphia, at 3 PM Sunday, a concert sponsored by the Philadelphia Classical Guitar Society.