Bloody Sunday

Released: 2002

Genre: Drama

Synopsis: A brilliant—though, at times, painful to watch—dramatization of the January 30, 1972, civil rights march in Derry, Northern Ireland, led by activist-politician Ivan Cooper. The march began peacefully, but it ended in a hail of gunfire. In just 10 minutes, 14 civilians lay dead in the streets, shot by members of the 1st Battalion of the British Parachute Regiment; 12 others were wounded. Two more were struck down by British armored personnel carriers. (And the official whitewash virtually on the spot.)

Why it’s one of the best: Written and directed by the innovative filmmaker Paul Greengrass, “Bloody Sunday” is shot in a documentary style, with handheld cameras. It’s all blur and herky-jerky motion, like Vietnam battle footage.

The technique yields a film of compelling immediacy. We feel as if we are all on hand in the Bogside on that awful day, marching alongside Cooper, Bernadette Devlin, Father Edward Daly—and young protestor Gerald Donaghy, who, with so many others, took a fateful wrong turn on a day when the British troops assigned merely to stop the illegal march turned instead, all too easily, to indiscriminate slaughter.

Donaghy died that day, shot in the belly.

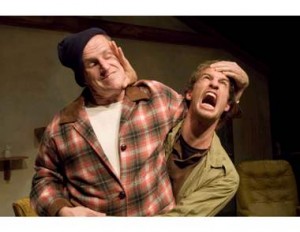

Two performances are particularly noteworthy. The Northern Ireland (Coleraine) actor James Nesbitt—if you watch BBC America, you may know him as Murphy of “Murphy’s Law”—turns in the finest performance of his career as Ivan Cooper. Cooper was then a member of the Northern Ireland Parliament who led the ill-fated march.

The film turns on Cooper’s actions on that day—from the morning, when he and others still dared to hope that they might be allowed to march in peace, to the news conference in the aftermath of the massacre in which he warned the British government that its actions had “given the IRA the biggest victory it will ever have. All over this city tonight, young men, boys, will be joining the IRA, and you will reap a whirlwind.” Watch Nesbitt’s face as the names of the dead are read out. You’ll see why he just might be Ireland’s best actor.

The veteran British actor Tim Pigott-Smith plays the cold, pitiless Major General Robert Ford, the British Army’s most senior officer in Derry on the day the Paras ran rampant. He played a similar character, in a way, in the BBC mini-series “The Jewel in the Crown,” about the last days of the British Raj. Pigott-Smith masterfully portrays that odd combination of bloodlessness and bloody-mindedness characteristic of so many British military men, particularly in colonial settings.

As I say, “Bloody Sunday” is not easy going. But if you want to understand and appreciate the history of Northern Ireland and the “Troubles,” this film is indispensible.