Melissa Lynch

“When it’s over, I want to say all my life

I was a bride married to amazement.

I was the bridegroom, taking the world into my arms.

When it’s over, I don’t want to wonder

if I have made of my life something particular, and real.

I don’t want to find myself sighing and frightened,

or full of argument.

I don’t want to end up simply having visited this world.”

~ Mary Oliver

Melissa Lynch wasn’t here long–she died in a car accident on December 30 at the age of 27–but no one would ever call her a visitor to this life. She grabbed it, embraced it, and, on occasion, frog-marched it where she wanted it to go.

A prolific actress—she appeared in more than 17 productions in Philadelphia—the Mayfair native was poised on the brink of her best year ever. She was engaged to be married on June 18 to William Seiler, a man, friends say, “she adored.” She had roles in four major plays, including one in which she was to play 8 different characters. Directors had started calling her. Even when she played smaller parts, reviewers couldn’t help taking note of her performances. In fact, said a college friend, Rebecca Godlove, “she could have a nonspeaking role in a play and still get noticed. In college, she played a mute child in a play and got rave reviews.”

Critics called her “dazzling,” “sparkling” and “luminous,” descriptions echoed by those who knew her, a powerful reminder of why actors have come to be called “stars.” But a reminder, too, that there are those among us who harbor an unquenchable inner light.

“She just radiates,” says Kathryn MacMillan who directed Lynch in her last play, the highly acclaimed production of Chekov’s “Uncle Vanya” for the Lantern Theatre Company. In fact, MacMillan says, she hesitated inviting Lynch to audition for the role she played, the “plain” Sonya, because Lynch was “too beautiful.

“She shone and there’s no dimming that and there’s no way I would want to,” said MacMillan. But MacMillan had seen Lynch play against type before—as the matted-haired, dirty invalid in Inis Nua Theatre Company’s production of “Bedbound,” a powerful work by Irish playwright Enda Walsh. “I could barely breathe all through that show, and yet through all the perfectly awful, disturbed misery, I found myself thinking, ‘she’s so amazing, she’s so amazing.’ For the first time I started to appreciate the range of things she could do. And I thought, if [Inis Nua artistic director] Tom Reing could make her ugly, why not?”

Her friend and frequent co-star, Doug Greene, who last appeared with Lynch in “The Duchess of Malfi” for the Philadelphia Artists’ Collective in September 2010, says that Lynch didn’t seek out the glamour roles, though they could have been hers for the asking. She was petite, with blue eyes and long blonde hair that she was perfectly willing to dye or hack if the character called for it. In “Bedbound” her face was smeared with sooty makeup and her usually sparkling teeth looked like a brush hadn’t been near them in a decade.

“She was a really beautiful girl and could have taken an easier road playing the beautiful girlfriend and wife, but she had a lot of depth as an actor and wasn’t satisfied just playing the girlfriend,” says Greene. Tellingly, though she was playing such a glamour role in “Duchess,” what reviewers saw in her portrayal of the conniving mistress of a Cardinal was “evil.”

But off stage, the only thing wicked about Melissa Lynch, her friends and colleagues say, was her sense of humor. “The first thing she would want me to say was that she was hilariously funny,” says Jared Michael Delaney, assistant artistic director of the Inis Nua Theatre Company, which produces modern plays from the UK and Ireland. “She had a really wicked and sharp sense of humor that could at times be terribly crude and at times incredibly clever.”

When her co-stars recall a performance with Lynch, it’s always marked by the memory of a recurring joke, usually made at their expense. Brian McCann, who played Lynch’s father in the poignant, violent, demanding play “Bedbound” last year, says she cracked him up before every performance when she would turn to him and mutter, “Now don’t f— this up for me.”

The other thing they recall is an outsized personality. “She was loud. She was opinionated. She loved to laugh and cause a scene. She could be as proper or as unladylike as you could imagine, depending on her mood,” her Clarion College classmate Rebecca Godlove wrote on her blog shortly after Lynch’s death.

And there was magic: “The girl was so passionate about everything you could almost feel the sparks crackling in the air around her,” Godlove wrote.

“I spent most of my time with her laughing and having a good time,” says Greene. “She was effervescent—and I don’t know too many people I would describe as effervescent. She had that ‘life of the party’ personality.”

She was also a true and loyal friend, a rare find in a world—the theater—that can be competitive, even cutthroat, and soul-crushing. “She was everything you want a friend to be—deeply loyal, but someone who would always tell you the truth, what you needed to hear whether you wanted to hear it or not,” says Delaney.

Many of those friends repaid that loyalty by waiting for hours on a cold winter evening in a line that stretched outside the Wetzel and Son Funeral Home in Rockledge and around the block, just to express their sorrow to Lynch’s family—father, Michael, mother, Madeline, and siblings Tina, Michael, Joseph and Theresa, and Lynch’s fiancé, Bill. And they were there the next day, at the gravesite in Whitemarsh Memorial Park in Horsham, where they joined her brother Joe in an impromptu and tearful version of “Danny Boy.”

Those who knew her as a friend admit that it’s been difficult coming to grips with the sudden finality of her death. “I’ve lost a lot of family members but this is the first friend,” says Delaney. “This is a new kind of grief for me personally.”

Those who knew her as a colleague, a co-star, or a character struggle with other feelings: Who will replace her? “To work with her is to love her instantaneously,” says MacMillan. “There are people who just saw her on stage and feel this loss. I know lots of actors who were looking forward to working with her. After ‘Uncle Vanya’ she came up to me and grabbed me by the shoulders and said, ‘I f’n love you. Can we do this again soon?’ And I said, ‘Yes, as soon as possible, please!’ I was so filled with the potential for this new friendship and a new collaborative relationship that I feel something important has been stolen from me, something that I wanted really bad.”

A remarkable, generous actress, Melissa Lynch was above all dedicated to her craft, one she chose as a child after seeing an ad for auditions for a local community theater. She starred in several musicals while she was a student at St. Hubert’s Catholic High School for Girls and in 25 productions while she was an acting major at Clarion.

“In school, most actors portrayed different intensities of themselves,” says Godlove. “Not Melissa. She had these moments of introspect when she was finding a character and it was magic. She could play anything and anyone. My last play in college was [Shakespeare’s] Henry V and the cast was almost all female. Melissa played Henry V and I played her comedic foil, her loyal Welsh sidekick who hated the Irish which was ironic since she played so many Irish roles. Watching her, you forgot she was a woman. You didn’t look at her and think, ‘that’s a girl playing a King.’ You thought, ‘that’s the young Henry V.”

Though she made it look seamless on stage, acting wasn’t effortless to Lynch. Inis Nua’s Tom Reing recalled her getting “crazed and panicked” by a part at first, “then she would see the humor in it and calm down.”

For her performance as a medical student in Inis Nua’s production of “Skin Deep,” by Paul Meade, Reing recalled, she had to jump rope while trying to memorize medical terms. “One day during rehearsals she came to me and said, very seriously, ‘Tom, I gotta talk to you.’ I thought she was going to tell me she got another gig with a bigger company, but she says, ‘I can’t jump rope.’ So she took the jump rope home and practiced memorizing her lines for that scene while jumping rope. I kept asking her about it and she said, ‘I’ll be ready for opening night, I’ll be ready for opening night.’ And she was.”

Lynch wasn’t above using the same methods that charmed critics and theater-goers to get what she wanted off stage either. Recalls Jared Delaney: “If she wanted something from you, you’d better do it. I wasn’t going to see her in her last play, ‘Uncle Vanya,’ because I don’t like the play and it’s 2-3 hours long. I told her, ‘Lynch, I’m sorry I can’t make it.’ She stood there looking at me, this tiny, beautiful blond girl. She put her hands on her hips and pointed at me and said, ‘You have to, I’m your girl.’”

He paused for a few seconds. “That’s why we’re dedicating the rest of our season to her,” he said softly. “She was our girl. And we loved her.”

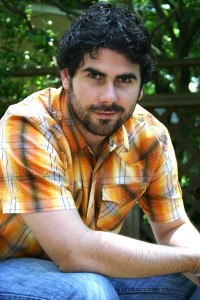

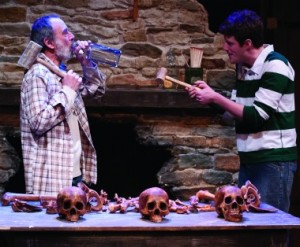

See photos of Melissa Lynch both off-stage and on. Thanks to Doug Greene and the Lantern Theatre Company for their help in assembling these photos.