History class is in session. It’ll only take 75 minutes, but at the end you’ll know everything.

You’ll know how empires rose and fell. You will learn how the British conquered the world through the sheer force of their withering contempt, why the Chinese just couldn’t stop building that wall, and why there are fewer countries more irrelevant than Australia.

And it’ll all be lots funnier than history as taught by Sister back in the fourth grade. She was a humorless cow, anyway.

“Long Story Short,” Colin Quinn’s acid interpretation of the events that shaped great nations and then brought them to their knees—punch-drunk, bewildered and condemned to keep committing the same disastrous mistakes over and over again—comes to the Susanne Roberts Theatre this week. The one-man show, directed by Jerry Seinfeld, runs from June 28 through July 10, 2011.

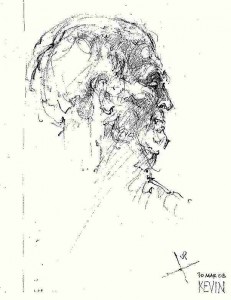

You’ll remember Quinn from his five-year stint on Saturday Night Live. His face redefines the meaning of craggy, and his widow’s peak carves out an impressive capital letter M across his forehead. Quinn has amazingly literate comedic sensibilities, and he offers up some head-spinning observations on the human condition, but the lines are delivered in a streetwise Brooklyn-ese, with a voice that sounds like a truck dumping a load of crushed rock. He stalks the stage (with a crumbling Roman amphitheatre as a backdrop), making some astonishing points as he goes along. For example, a riff in which he compares Antigone of Greek mythology to “Jersey Shore’s” self-obsessed Snooki, or re-envisioning Caesar as Goodfella mobster Ray Liotta. The show is fast-paced—in Quinn’s world, each empire rises and falls in about ten minutes’ time.

Of course, you’re not meant to take any of it seriously. Scott Brown, writing for New York Magazine, recalled a quote from director Seinfeld in which he described the making of “Long Story Short” as “taking a fatuous premise and proving it with rigorous logic.”

We chatted with Quinn by phone this week, and here’s what he had to say about the show and his Irish-American upbringing.

Q. A headline for the Hollywood Reporter review described your show like this: “The History Channel meets Comedy Central.” It was actually a pretty good review, but that kind of Hollywood pitch line description doesn’t really measure up to what you’ve done. The history of the world in 75 minutes is an Olympian task. How hard was it to pull all of that material together and make all the connections?

A. It like to play around with this stuff, anyway. I always think in terms of “combinations.” It’s always in my head somehow. It’s all people stuff to me. Altogether, it took a few months to bring together—different hours, different times.

Q. If you’re going to talk about the British Empire and the Roman Empire (and more), you really do have to have some sense of history. You couldn’t have tackled the “demise of empires” with just a Cliff’s Notes knowledge of history. So I suppose I could put this more delicately, but how did you get so smart?

A. Most of it, I feel like its common enough knowledge. And we (comedians) have a lot of free time. We can read any time we want. I read a lot. I don’t reads that much history—I was never all that interested in history. I’m really more interested in the global village. I feel like everything else. These connections have been going on since time began.

Q. For those who haven’t seen the show, how did you figure out that you could make the connection between Antigone and Snooki?

A. That junction is just based on the fact that what people used to watch is not like what people watch now. (Now) we see Snooki crying on her knees over the loss of her cell phone.Most people wouldn’t know who Antigone is, but I went to a few acting classes so I know my stuff.

Q. You’ve probably been asked this before, but did you have any qualms about how or whether stand-up translates to a long-running Broadway monologue—the kind of story-telling that has been compared to the work of Spalding Gray? What were the challenges?

A. My own form of comedy is long-form, rambling comedy. I just wanted to do something thematic for a change of pace. To me, that was really like a natural state. It wasn’t like I was doing a bunch of one-liners before that, anyway.

Q. We’re an Irish web site, so of course we need to ask you something Irish. Happily, you’ve already gone there with an earlier show, “Colin Quinn: An Irish Wake.” And here again you’ve been lauded for your story-telling powers. The New York Times review described you as a kind of modern-day incarnation of the Irish “seanchai.” (“Story-teller,” in the Irish language.) You grew up in Brooklyn, coming from an Irish family, and knowing a lot of the local Irish–evidently providing you with a wealth of material. Can you tell us how growing up Irish influenced you?

A. Irish people, they like to read more than most people. I feel like that helps a lot. And I feel like Irish people are very verbal. I definitely feel like my Irish blood helps me to be a performer and a writer of comedy.

For more information on the show, check out the Philadelphia Theatre Company Web site.