Chuck Connelly

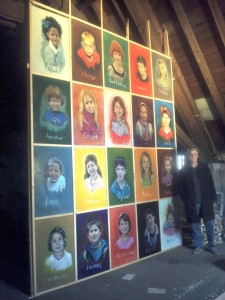

The last time we spoke with the world-renowned East Oak Lane artist Chuck Connelly, back in April, he had recently completed a poignant collection of portraits depicting 20 small children, all of the canvases bound together in an imposing 10- by 12-foot wooden frame. They were the children of Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn., whose lives were cut all too short last December at the hands of a disturbed young man armed with a Bushmaster XM15 semi-automatic rifle.

Connelly was frustrated by his inability to move the massive display out of the old barn where the imposing work was stored, and into a far more fitting public space. Preferably in Newtown—but failing that, anywhere people could stand in front of this ambitious, larger-than-life undertaking, and literally come face to face with the victims as seen from an artist’s unique perspective. Each portrait springs from the depth of Connelly’s own sorrow and anger, a modern-day wailing wall.

At the time, in spite of repeated efforts by neighbor, friend and author Marita Krivda Poxon, there were no takers. Connelly was disheartened but undaunted. “I’m not done until I get this someplace and people stand in front of it,” Connelly said at the time. “That is my goal. It needs to be somewhere.”

Now, as the solemn one-year anniversary of the school shooting approaches—it’s December 14th—Connelly is about to get his wish. His “Children of Sandy Hook” will be on display from December 9 to 16 in the Villanova University Art Gallery, located at the university’s Connelly Center. On the 14th, Connelly will be the guest of honor at a gallery reception.

Stuart Tate, the carpenter who put the frame together, took it all apart again, gingerly moved the portraits out of the barn, and dropped them off at Connelly’s rambling house earlier this week. On Saturday morning at 10, Connelly and Tate will load of the portraits into a truck and deliver them to the Connelly Center for final assembly. “He (Tate) is gonna put it together. I’m gonna help, and the guy who runs the gallery, he knows woodworking, and he’ll be able to help.”

For now, the portraits are scattered throughout Connelly’s cluttered house, virtually every room of which is stacked with canvases of various shapes and sizes, all leaning against the walls like decks of cards. One glance, and you know right away that Chuck Connelly doesn’t ascribe to any particular school. Forget realism. Forget abstraction. Connelly belongs to only one school, and its all his own—that’s one of the reasons his work is so famous and highly regarded. He paints whatever suits his mood. He has no plan. Whatever comes off the brush is just what it is.

In one room, you might stumble upon a huge canvas bedecked with loosely nonrepresentational geometric patterns. In another room, you could find a portrait of a woman who sells pies. Or perhaps one of countless renderings of his rotund, obviously spoiled calico cat, Fluffy. Fluffy is clearly one of Connelly’s favorite subjects. The fact that such an original thinker keeps a cat with such a commonplace name is just one more visible symbol of his incongruity. Don’t even think about trying to pin him down.

In many respects, his kitchen is a lot like the rest of the house. Above the dark wood wainscoting hang more paintings. A clown. A flower. A bird. Strings of miniature lights hang across one window. There are neat little stacks of cat food on the counter next to the sink. A bottle of ibuprofen. And another bottle, multivitamins.

Next to the wall, there’s a well-worn utilitarian wooden table, surrounded by mismatched chairs. On the table, an overripe banana in a bowl. A bag of nacho chips. Potatoes in a plastic mesh bag. A box of store-brand turkey stuffing. Saltines.

And a carton of Timeless Time cigarettes, a cheap Korean brand.

One of those cheap cigarettes is almost always dangling from his lips. His undisciplined mop of graying hair is perpetually enwreathed in a halo of blue-gray smoke.

We’re in the kitchen with Poxon, talking about the upcoming exhibition. It’s the immediate cause of Connelly’s almost palpable anxiety. He’s guardedly optimistic, but things could still go wrong. He’s been disappointed before. You could take him for a cynic, but that’s too simple. George Carlin once said, “Scratch any cynic and you will find a disappointed idealist.” That’s probably a more accurate assessment of Chuck Connelly, a man consumed by his passion for truth and beauty, in a world to often devoid of both. But for now, just for a moment, he appreciates the opportunity to have at least this ambition fulfilled.

“I’m grateful,” he says, “but I’m not done yet. I’ll really be grateful when it’s all done and up there. I’ll worry until it’s up on the wall, and there you go.”

How the cause of “Children of Sandy Hook” came to be taken up by Villanova is a bit complicated. Unbeknownst to each other, Connelly and Poxon were working along parallel paths. Connelly met a guy at a party, who knew another guy in a position of authority on campus. At the same time, Poxon had made connections through the Irish Studies department that ultimately led to the president of the university, Father Peter M. Donohue, who is also an artist. And the head of the gallery, Father Richard G. Cannuli, is a painter of icons. Between Connelly and Poxon, they scored a long elusive triumph.

“This president is Irish, and I think he liked the whole thing,” says Poxon. He could see that it’s a sacred time, it’s Christmas, and it would get the students to think about this. And there are some students from Newtown, and they’ll be there.”

Connelly, for one, hopes they’ll be there. He hopes a lot of people will be there, and he hopes they will come to understand that his memorial to 20 lost children is very different from anything he’s ever done. It came from a different place. And for a brief moment his mood shifts to one of optimism.

“This, I dreamed up out of my head. It was created by this tragic incident,” Connelly says. “Now, it’s become real. Now, people are involved. That’s the miracle.”