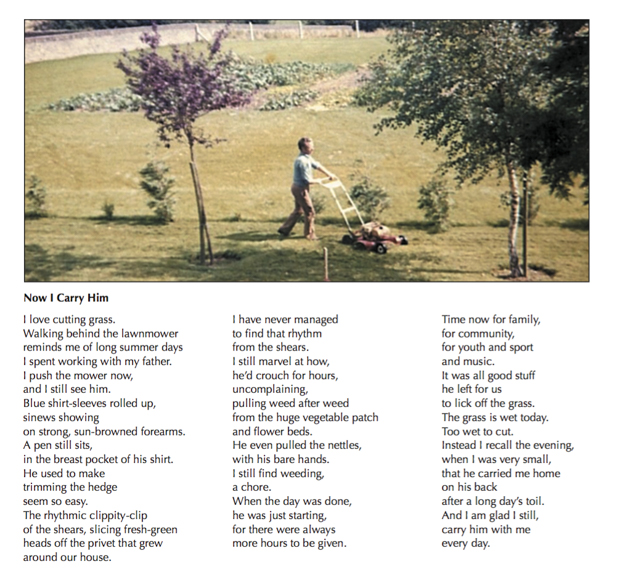

Anakronos: Caitríona O’Leary, Deirdre O’Leary, Nick Roth, and Francesco Turrisi (photograph by Tara Slye)

It’s been almost 700 years since Kilkenny’s discordant 14th century Bishop of Ossory, Richard de Ledrede, held sway over the souls of his parishioners, but 17 of his medieval poems are on track to reach the listening ears of a 21st century audience on the newly released CD, “The Red Book of Ossory.” And thanks to Caitriona O’Leary and the group Anakronos, what an innovative and exalted musical experience it has been transformed into.

But in order to wax properly eloquent on the newly released CD, there first needs to be some background on the origins of the Red Book of Ossory itself.

Richard de Ledrede was a man of massive contradictions. English-born, and a student of the Franciscan order, he was appointed Bishop of Ossory in 1317 by the Papal Court in Avignon. Immediately after his arrival in Kilkenny, he set about doing things his way, and his way meant a strict adherence to the Church laws and beliefs as he saw them. He set a high bar where morality was concerned and that included a moratorium on the singing of “bawdy” secular songs. He composed 60 poems that are included in the Red Book of Ossory (the original manuscript is housed at St. Canice’s Cathedral in Kilkenny) with the instructions: “for the vicars of the cathedral of the church, for the priests and for his clerks, to be sung on important holidays and at celebrations in order that their throats and mouths, consecrated to God, may not be polluted by songs which are lewd, secular and associated with revelry and since they are trained singers let them provide themselves with suitable tunes according to what these sets of words require.” Poetry that Caitriona O’ Leary describes as “beautiful, esoteric and richly imagistic.”

Exquisite and divine poetry that came from the same mind, of the same man, who in 1324 would be responsible for the first woman burned at the stake in Europe for the crime of witchcraft.

In his fervent dedication and adherence to the very highest principles of the Church, de Ledrede determined there was a “diabolical nest” of heretics in his midst, and held an inquisition into the source of the sorcery. He settled upon a wealthy woman who had been thrice widowed and was on her fourth husband, Dame Alice Kyteler. She had inherited money from each of her late husbands, and as a smart businesswoman, was able to amass a small fortune. It also made her a target for the types of accusations that in medieval Ireland meant she must be a witch.

The Bishop of Ossory declared that she had “denied Christ, enchanted the citizens of Kilkenny with magic potions—made from entrails of cocks which had been sacrificed to demons, dead men’s nails, hair and brains of boys who had been buried unbaptised—all cooked up in the skull of a decapitated thief, that she had an incubus named Artisson with whom she had sex and who manifested as either a cat, a shaggy black dog or a black man, and that she murdered her first three husbands and was poisoning her fourth.”

Dame Alice, fortunately for her, had powerful friends and associates who were able to get her out of Ireland to safety; she disappears from history after making her escape. Her servant, Petronilla de Meath, unfortunately for her, was left behind to answer to the charges of witchcraft leveled against her. She was imprisoned, and under torture, confessed to being a practicing witch alongside Dame Alice. Among the misdeeds she took responsibility for was the ability to concoct a potion that when applied to a broom, enabled Petronilla and Alice to fly. Petronilla de Meath was flogged, forced to make a public confession, and then burned at the stake on November 3, 1324.

As she began researching the poetry, what drew O’Leary to the writing of de Ledrede “was not just its antiquity or obscurity, but the fact that the bishop—he was a witch hunter … he seems like such an evil, tormented man. But who I’m sure thought he was doing the right thing, I’m sure he thought that the universal powers were behind him … the same mind that wrote these songs with beautiful imagery, it was the same mind that came up with completely hallucinogenic and out-there charges of heresy. I find it really interesting that [these are] the same kind of creative powers within the brain at work.”

The fact that there was no music left from 1320s Ireland that she could find meant that O’Leary had to dig deeper and work from 700-year-old clues. “It was the bishop’s instructions at the start of the collection of poetry to the skilled singers of the choir that they should find the songs that would suit. And so I did. I found medieval music from England, France, the Netherlands, and Italian music from the time, that worked with the words. And then to just take it somewhere else completely—since I was already playing around with things—the band is actually made up of jazz and contemporary music players. So, medieval music but done in a jazz, contemporary way and it’s very cool. The poems were written in Latin, and I sing them in Latin, but I sing them in what’s considered contemporary Church Latin. Which is how Latin is sung in Church.”

Caitriona O’Leary’s wonderfully eclectic career is an ode to her talent for resurrecting timeless verse, rescuing it from obscurity, infusing it with innovative music and giving it contemporary context. For “The Red Book of Ossory,” she has assembled a sublime combination of musicians for the group Anakronos: Deirdre O’Leary on clarinets, Nick Roth playing saxophones and Francesco Turrisi on keyboards and percussion. The result is an originative fusion of medieval and jazz; the effect on the senses is like being wrapped in a cocoon of exalted sound.

The album succeeds mightily in its intent to explore the dualistic nature of Richard de Ledrede through its genre-bending stylistic conceits. The combination of live, acoustic instruments and the merging of medieval music, Celtic music, jazz, world beat and even contemporary electronic-inspired styles like trip-hop result in an anachronistic yet musically cohesive work.

Several of the tracks, such as “Canite, Canite,” “Regine Glorie” and “Ecce Sacerdos Magnus” are underscored by an ominous electronic drone or bass line. The gorgeous vocals, the organic woodwind instruments and the almost African-inspired percussion float over a foundation of electronic textures. The beauty of the language and melody is juxtaposed against a foreboding tension or even a sense of dread. Fitting, considering the author of the poetry was a man who was at once an extraordinary writer capable of creating beautiful lyrics, and also a monster who accused women of witchcraft and had them burned at the stake.

What may possibly be the strongest, yet most easily unnoticed, element of this album is its percussion. Impeccably produced and performed with all manner of drum circle instruments, in some songs such as “Regine Glorie” and “En Christi Fit Memoria” it adopts a trip-hop sensibility with slow, plodding, groovy rhythms. Other tracks de-emphasize percussion and some forgo it entirely, instead opting to bring O’Leary’s haunting operatic vocals to the forefront. On “Consendit Salamon Ventrale Ferculum” the atmosphere is maintained by the core melody carried by both the vocals and a baritone saxophone.

From time to time, like on the instrumental “The Flight of Dame Alice Kyteler,” the musicians make a full embrace of their jazz influences and allow the saxes and clarinets to blare erratically in brief spurts of freeform bliss. Tracks like the ambient “Ecce Sacerdos Magnus” and the smooth jazzy penultimate song “Verum Est” are hypnotic. Utilizing their instrumentation perfectly, these songs are both keyboard driven. “Ecce” in particular is a six-minute instrumental piece with captivating keyboard textures; woodwind instruments softly intrude near the end, lulling this gorgeous piece to a close. “Verum” begins with almost a full minute of O’Leary’s isolated vocals, until the song’s introduction of spacey keyboards and a freeform saxophone propel the track into glorious smooth jazz.

“The Red Book of Ossory” is a singularly effective combination of medieval melodies and contemporary psychedelic jazz, triumphantly portraying humanity’s duality in its music. It’s undeniably beautiful, but always with some dissonance—often subtle—sleeping beneath each track.

For more information, visit Anakronos’ website and check out the trailer for “The Red Book of Ossory.”