“Through their personal interaction with the Irish Bridget, native-born Americans came to see the Irish less as ‘others,’ and more as fellow humans. Credit is due to the Irish Bridget for pioneering the way for the Irish to become accepted by native-born Americans and for helping the Irish, as a group, move into the American middle class.” ~ Margaret Lynch-Brennan ~ The Irish Bridget: Irish Immigrant Women in Domestic Service in America, 1840-1930

“Through their personal interaction with the Irish Bridget, native-born Americans came to see the Irish less as ‘others,’ and more as fellow humans. Credit is due to the Irish Bridget for pioneering the way for the Irish to become accepted by native-born Americans and for helping the Irish, as a group, move into the American middle class.” ~ Margaret Lynch-Brennan ~ The Irish Bridget: Irish Immigrant Women in Domestic Service in America, 1840-1930

Just to be clear, the term Irish Bridget, coined sometime in the mid nineteenth century, was not meant to be in any way complimentary. Beginning around 1840 and continuing in increasing numbers through the years of An Gorta Mór and beyond, young Irish women immigrated to the United States. What made these women different from the ones who had come before them was their ages (some as young as 13), their single status, they often traveled unaccompanied, and they arrived determined to work hard, save money and eventually marry and have families of their own. Their best path to realizing these dreams, they discovered, was to obtain employment as live-in domestic servants in the homes of middle and upper-class families.

As the numbers of young Irish women employed in domestic service in the U.S. grew, a stereotypical representation of the Irish maid developed; she was characterized as inept, ill-mannered, and incompetent. She was seen as something of a buffoon. The name Bridget stuck to this version of the girl who arrived from Ireland and found herself willing and eager to work, but untrained for the duties and responsibilities she would face in the American household. While the exact number of Irish born women who worked in domestic service from the second half of the 19th century to the first third of the 20th century will never be known, it’s been estimated that in East Coast cities in the 1850s, they made up the largest single group among servants. And by 1900, 54 percent of women who had been born in Ireland and were living in the U.S. were employed as domestic servants, and another 6.5 percent worked as laundresses.

During that time period, having the means and ability to employ live-in help became a symbol of status, and rising middle class families liked having a young woman dedicated to housekeeping, cooking and nanny duties. Irish girls could be counted on to work 6-7 days a week, 10-12 hours a day and assimilate into the household. On the other hand, most of them arrived untrained for their new duties and responsibilities. Life in rural Ireland was far different from the bustling American households they were moving into. Food was scarce back home, and learning the culinary arts hadn’t been part of their upbringing. Caring for the small, one-or-two room houses with dirt floors they grew up in didn’t provide them with the housekeeping skills they would be required to utilize. Their keenness to learn made them invaluable, but it was this initial lack of knowledge that led to the creation of the “Irish Bridget” stereotype. In fact, the name “Bridget” became so synonymous with the word “maid” or “servant” that a significant number of Irish women who had been baptized with the moniker changed their names upon arrival on American shores. Word had reached them back home of the negative connotation and they didn’t want to arrive already carrying the burden of that prejudice with them.

An early use of the term appears in the June 23, 1859, edition of the Freehold, N.J., newspaper, The Monmouth Democrat. In an editorial defending the respectability of American born working girls, the author slams those who are Irish-born in comparison: “One is not to possess the idea that one who supports herself is to have the red face and brawny arms of an Irish Bridget.” The meaning being that the Irish working girl is of a lower character and class than other young women who have to earn a living. In another article, this one from the March 11, 1887, Brooklyn Times Union, the writer of the piece makes it clear that Irish girls have so demeaned the position of domestic servant that self-respecting “American” girls will no longer consider working a job so beneath them: “The scorn is largely due to the inferiority of the class which has monopolized American kitchens. Thousands of illiterate Irish girls, their only endowment crude physical strength, have been borne across the Atlantic to American shores. So completely have they taken possession of the domestic service of Uncle Sam that the Irish name Bridget has become a synonym for the class. Native American girls, seeing the stigma which rests upon this employment, refuse to enter it.”

The Irish Bridget became a fixture in American pop culture of the day. In the 1900 novel, “The Last Lady of Mulberry,” by Henry Wilton Thomas, a reviewer for The Nashville Banner praised the “very interesting diversion” made “in the introduction of a good-natured, honest Irish Bridget.” In the March 18, 1875, review of a local theater production, The Woodstock Sentinel assigns this praise to one of the actresses: “Katie St. Clair delineated the Irish Bridget very nicely.” Songs, poems, jokes, cartoons and other illustrations from the era also reflected the caricature of this less-than-competent (but frequently affectionately amusing) young Irish servant.

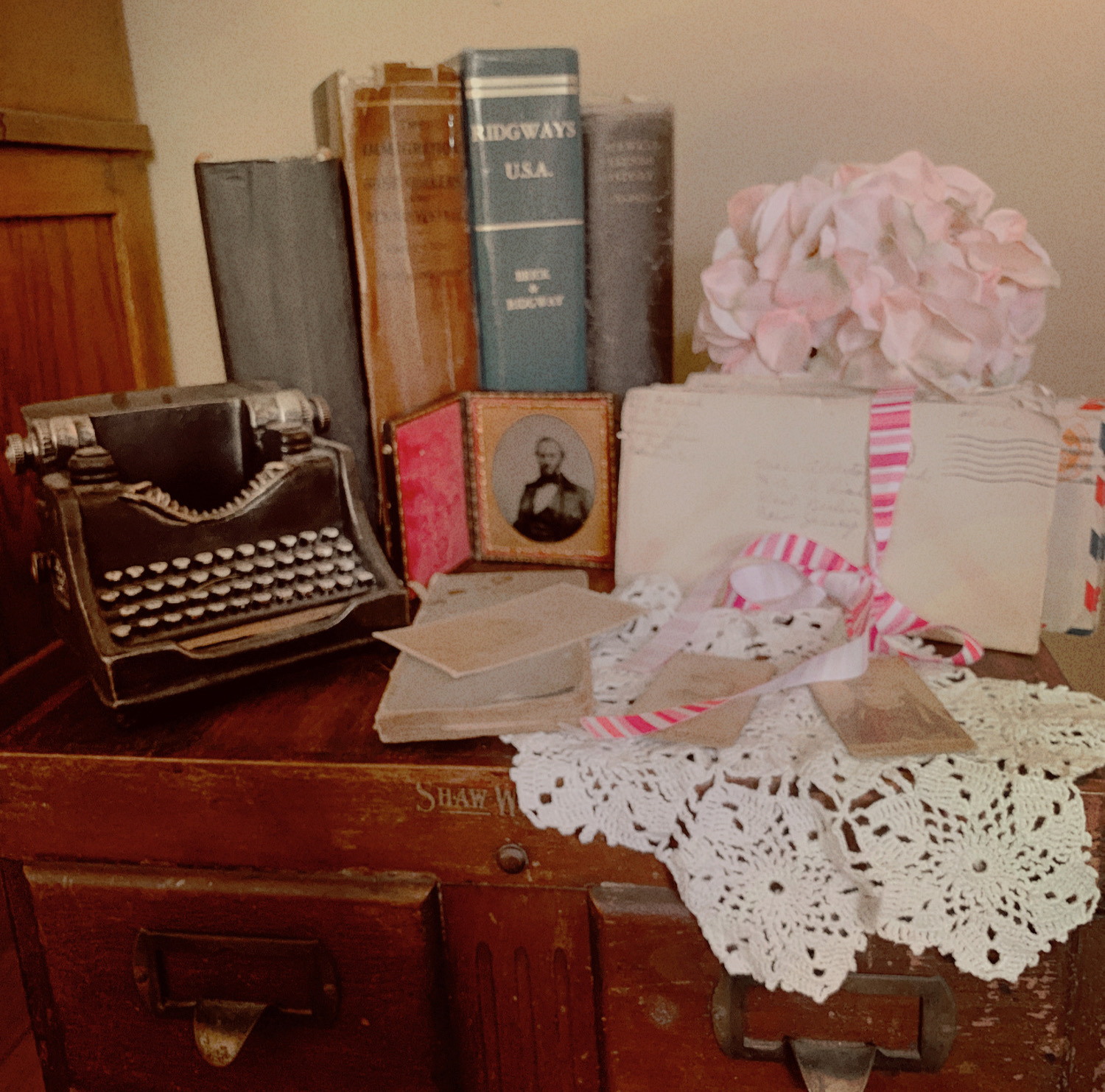

But as times changed, and attitudes shifted, the stigma surrounding the name Bridget and its attachment to the stereotype of the lowly Irish servant girl gradually faded from the public awareness. This was due in no small part to the Irish Bridgets themselves. As Margaret Brennan-Lynch writes, “Their gender and their domestic service, the form of labor in which they engaged, distinguished the experience of female Irish immigrant domestics from the experience of male Irish immigrants.” This created an invaluable up-close-and-personal relationship between established Americans and the newly arrived Irish that helped to make the outsider more of an insider. The Irish Bridget became one of the family. Additionally, this allowed the young immigrant to learn American ways through her firsthand experience of living in the families’ homes, a unique interaction that would play a large part in how quickly the Irish came to assimilate into their new culture. As these young domestic servants began to marry, move out and create families of their own, they were able to establish homes that mirrored those of the families they’d lived with. In this way, the Irish Bridget was directly responsible for insuring that her children were born into a life where they were more easily accepted.

Today, the Irish Bridget can be remembered for the strong role she played in allowing the Irish to speed their acceptance into American society. These were innovative women who found employment within families and learned from their interactions with them. They saved money and brought family members over to join them. They aspired to marry and create their own families. When they weren’t working, they enjoyed social activities such as dancing, and they looked to their neighborhood church to maintain ties to their religion and culture. Ultimately, they paved the way for Irish immigrants into the larger American society, and formed the foundation for future generations of Irish Americans to succeed in all walks of life.