“I’ll take you home again, Kathleen, across the ocean wild and wide

To where your heart has ever been since first you were my bonny bride

The roses all have left your cheek, I’ve watched them fade away and die

Your voice is sad when e’er you speak and tears bedim your loving eyes.”

The familiar lines of “I’ll Take You Home Again, Kathleen,” penned by Thomas P. Westendorf in 1875, evoke all the emotions associated with the theme of Irish immigration to the United States, particularly in the years after An Gorta Mór. They are the lyrical depiction of the sadness and longing experienced by the millions who crossed the Atlantic for a better life; the trade-off being they would never see their homes or families again.

The familiar lines of “I’ll Take You Home Again, Kathleen,” penned by Thomas P. Westendorf in 1875, evoke all the emotions associated with the theme of Irish immigration to the United States, particularly in the years after An Gorta Mór. They are the lyrical depiction of the sadness and longing experienced by the millions who crossed the Atlantic for a better life; the trade-off being they would never see their homes or families again.

It’s the prevailing image we all have, and for the most part it’s true. Although many Irish would be reunited with family members who had already come over, or relatives they would help to bring over at a future date, and letters were exchanged, a return journey was out of reach for the majority of those who immigrated to America.

But there are exceptions to every rule, and I’ve been intrigued by occurrences of “return migration” that I’ve come across over the years. Here are three different instances among those I’ve encountered.

The first, believe it or not, was in the 1600s. My earliest Irish ancestor to reach the shores of America was Miles Riley, born about 1614 in County Cavan. In 1634, he and his older brother Garrett arrived in the Virginia colony on the Bonaventure. Several years later, another brother, Thomas, joined them.

From what I’ve been able to glean, in the mid to late 16th century, the Clan Riley began losing a lot of their land and prestige. First to other clans, then to the English, and then through power struggles within the family. However, though their circumstances had changed, the brothers were not without means as they embarked on their new lives; they were given land grants and Miles is recorded as receiving an additional 1,100 acres in Virginia for sponsoring 20 immigrants in the 1660s.

But sometime in the early 1650s, Garrett found a way to return to Ireland as a landowner. He sold off his land grants in the colonies and bought his passage back to Ireland. He shows up on tax rolls in 1655 and 1665 as owning a six-room thatched cottage in Kells, County Meath. Exactly how and why this came about is a story still to be discovered, and hopefully there are records out there somewhere with more information.

The second account of return migration comes about 200 years later, from the family of Sister Frances Kirk. Though she never met her maternal grandfather, Michael Falls, Sister Frances listened closely to the stories her mother told her about him.

Michael, or Mickey, was born in the Glenelly Valley in County Tyrone. He never knew the exact year he was born, or what year his journey to America began, but as a boy of about 10 or 12, his mother told him she was sending him to the U.S. to live with an aunt in Kentucky. This was sometime in the 1850s, and not long before the Civil War.

Arriving at the harbor in New York with a note attached to him indicating he was to make his way to Kentucky, Mickey boarded a train with other young lads from Ireland. For over six weeks they traveled by train, stopping to stay on farms for a few nights at a time to do chores and help out. He got to his aunt’s boarding house in Kentucky, and settled into life there. During the Civil War, he would slip out at night to bring food and supplies to Confederate soldiers camped at the crossroads. It’s possible, but unconfirmed, that he may have also fought for the Confederacy.

After the war ended, he continued living with his aunt, working hard and saving as much money as he could. He became an American citizen, and decades later, some of his own children would come to the U.S. on his citizenship papers. The money he saved he hid in his mattress … until the day the boarding house caught fire and he lost everything. Discouraged and tired of life in his adopted country, Michael got the money together to buy his passage back to Ireland. Sometime around the late 1860s or early 1870s, he returned home to Tyrone, with a new suit and a fresh start. He married Jane Conway, and they had 14 children, many of whom later made their own journeys to America where they stayed and their families live today.

After the turn of the 20th century, the journey by ship became less arduous, and immigrants were able to make an occasional trip home for visits. And the records of these trips can provide valuable genealogical clues.

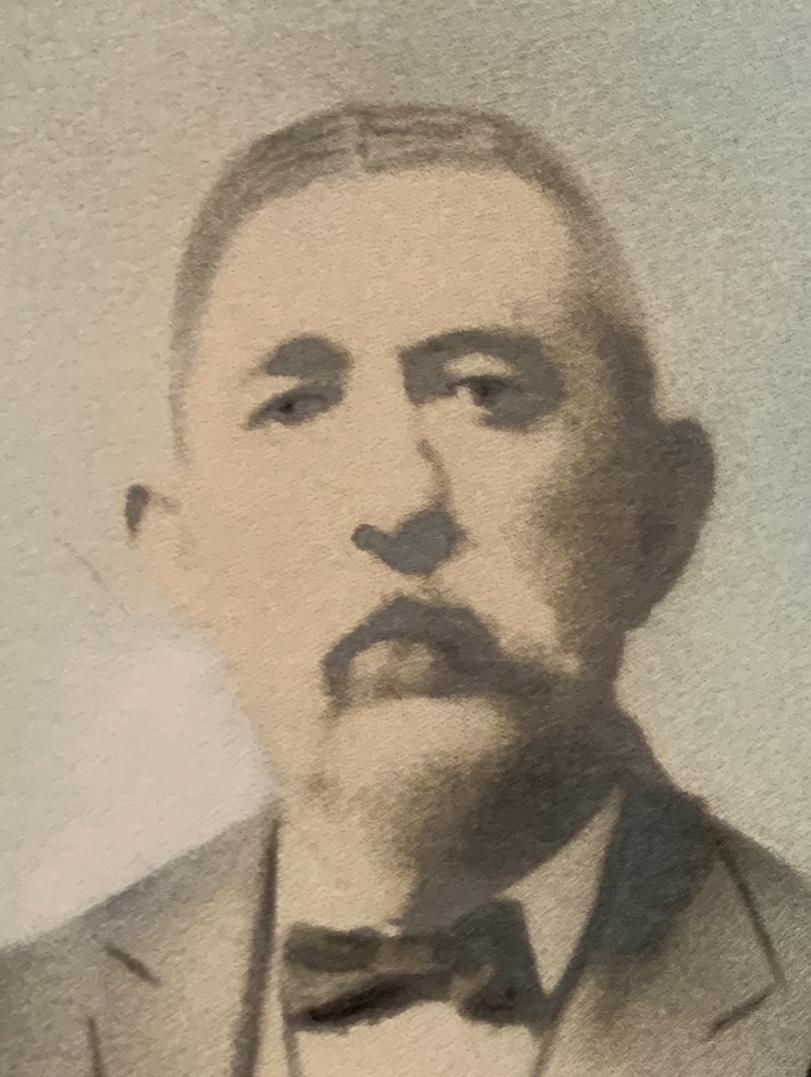

My husband’s Crowley family were said to have been from Cork, but no one knew exactly where they were from. I had discovered that his second great grandparents, Daniel Crowley (the man in the above photo) and Annie McCarthy, arrived in Philadelphia in 1903. But they had been living in Wales for about 10 years, and there was no information on the family back in Ireland, so still no clues as to where they were originally from. And then I came across a ship record for a Daniel Crowley, arriving in Philadelphia from Ireland, in 1913. He was by himself, 53 years old, a fireman and a permanent resident of the U.S. His home residence in Philadelphia matched up to the address of the Crowley family. This Daniel Crowley was the one I was looking for. And this Daniel Crowley was returning from a visit to his mother, Mrs. Mary Crowley, in Barleyhill, Rosscarbery, County Cork. I now had his mother’s first name, and the town and townland where his family lived. A huge and very welcome breakthrough.

While it may defy the expected experience of the Irish immigrant, the stories of those who tried America out and returned home are very real and incredibly interesting. There are more of them out there than you’d think, and they are a part of many families’ history.

Please check out the video I did for the Irish Diaspora Center: