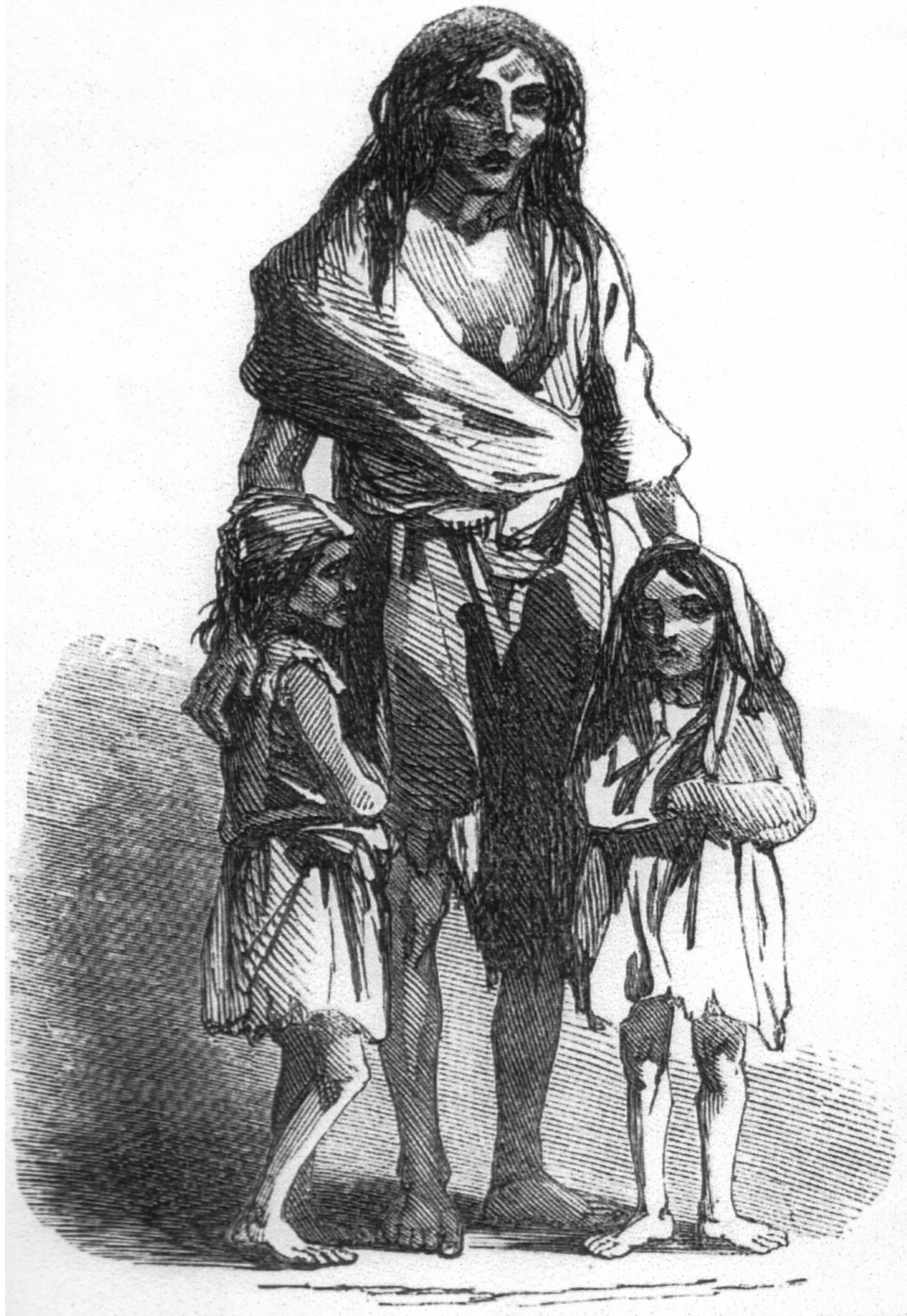

Between the years of 1848 and 1850, over 4,000 young women, ages 14 to 20, left Ireland’s workhouses for the shores of Australia as part of Earl Grey’s Orphan Scheme. They had been carefully selected as part of a plan to ease the burden of poverty and starvation during An Gorta Mor (The Great Hunger) in Ireland, while at the same time providing Australia with the female presence lacking in that country. For the girls who made the journey, it was a way of escaping a life of predetermined hardship for the promise of the unknown, the possibility of something better.

Between the years of 1848 and 1850, over 4,000 young women, ages 14 to 20, left Ireland’s workhouses for the shores of Australia as part of Earl Grey’s Orphan Scheme. They had been carefully selected as part of a plan to ease the burden of poverty and starvation during An Gorta Mor (The Great Hunger) in Ireland, while at the same time providing Australia with the female presence lacking in that country. For the girls who made the journey, it was a way of escaping a life of predetermined hardship for the promise of the unknown, the possibility of something better.

But not all the futures were to be created equal. Some would thrive, establish families and find happiness; others would struggle to survive, and some would end up dying in destitution. Catherine and Anne Hegarty from County Roscommon were two sisters who arrived on the same ship, but whose lives turned out very differently.

Catherine Hegarty is the second great grandmother of my “Aussie cousin” Carol’s husband, Terry. Terry didn’t know anything about this branch of his family, but in 2015 he decided to take a DNA test and start digging. Over the past five years, he and Carol have made some incredible discoveries about what brought his ancestors from Ireland to Australia, and along the way uncovered a story that deserves to be told.

Anne and Catherine’s ship, the Digby, docked in Sydney on April 4, 1849. It was expected that they would be hired out to employers as quickly as possible, and there would be a signed contract laying out the terms. It was also expected that they would marry; in many cases the orphan girls had a marriage arranged by a parish priest and the groom was an Irishman who had been transported to Australia as punishment for a crime committed. Upon their arrival, Anne and Catherine’s biographical information was recorded, as were all the new arrivals. It’s not known if the information they gave was entirely accurate, in other records their ages vary by a few years and though they said they could read and write, education in the workhouses was notoriously nonexistent. But Anne, the older sister, gave her age as 19, she was from Boyle, Roscommon, her parents were Andrew and Sarah (both deceased) and she was trained as a housemaid. Catherine gave her age as 17, and said she was trained to be a nursemaid. They both stated they had no relatives already in the colony, but a year later another arrival from Roscommon named Margaret Dolan arrived and named her relations in the colony as her cousins Anne and Catherine Hegarty. It’s not known if the three relatives ever met up.

Right from the start, Anne got off on a bad foot. It’s recorded that on July 14, 1849, just three months after their arrival, her indenture had been canceled. She also ran into trouble with the Water Police Office. Not having a job, and acquiring a record, would have made life difficult for her. On September 10, two months later, Anne got married in Ipswich to a man named Bartholomew Cullen. Not much is known about that marriage, other than they had two daughters (one who died in infancy) and Bartholomew, who was about 30 years older than Anne, passed away in 1854. What little else is known about the details of Anne’s life comes from records that Carol and Terry have managed to find. She had two other husbands (though no marriage records have been discovered) and a child with each of them. But this lack of information is in itself telling. Anne seems to have fallen through the cracks, and the final years of her life were spent in the Dunwich Benevolent Asylum in Queensland. Established as a home for the sick and the poor, the Asylum mainly housed the aged, and Anne died there on May 31, 1900. She was listed as age 62, born in Boyle, Ireland to Selina Reynolds and Andrew Haggerty. It’s not known what, if any, contact Anne had with Catherine during the 50 years after their arrival.

For Terry’s great-great grandmother, Australia provided her with a life in great contrast to her sister’s. Catherine was sent to Moreton Bay for her indenture, and though it had a reputation for being the place where “troublesome” girls were banished, there is no indication that Catherine was ever difficult, and her obituary describes her as having a “cheerful disposition.” But Moreton Bay, though known as one of the roughest of the penal colonies, was where Catherine met the man who became her husband, the father of her 12 children, and her partner in creating a happy and prosperous life. John Ford, born in County Galway about 1813 to John Ford and Catherine McCarthy, had been sentenced in 1840 to 15 years transportation for the crime of “simple burglary.” On July 8, 1840, John and his brother Thomas were both transported to Moreton Bay on the ship the Eden. Records list John’s age as 23, his description said he was Catholic, single, fair, ruddy with freckles and his occupation was as a laborer. John must have been an exemplary prisoner, because he was granted a “ticket of leave” in 1846, nine years earlier than his sentence had decreed, and received a conditional pardon in 1851. He became involved with St. Mary’s, the Catholic Church in Ipswich.

It was St. Mary’s where Catherine and John are believed to have met. The priest, Father Eugene Luckey, took an interest and an active role in looking out for the orphan girls, which included Catherine. He most likely introduced the two and encouraged the marriage. He certainly approved the marriage as he provided a “Permission to Marry” certificate to John. The couple wed on April 1, 1850, almost a year to the day after Catherine had landed on Australia’s shores. Whatever John’s crime of “simple burglary” entailed, he put that life behind him. After he was released, he worked on rural properties that he is thought to have owned. He and Catherine together built and ran the Beehive Inn in Rockton, about 18 miles south of Ipswich. Eleven of their 12 children survived to adulthood, and went on to have good jobs and families of their own.

John passed away in 1894, and Catherine lived on at their home until it was destroyed in a fire in 1900. From then until her death in 1914, she resided at the homes of her children. Catherine’s death notice commemorates a life well lived: “In the demise of the late Mrs. J. Ford, which occurred at the residence of her son-in-law and daughter…Ipswich has lost one of the oldest pioneers of the district – in fact, it is claimed that she was the oldest lady who had lived continuously in Ipswich, and she had reached the age of 80 years.” Another, more detailed tribute to Catherine, noted: “She was of a most cheerful disposition; and she watched the growth of Ipswich from a village of wooden and slab cottages. The deceased was intimately acquainted with most of the pioneers of Ipswich, West Moreton, and of the Darling Downs, and she had many experiences of colonial life…so she attained her often-expressed wish to die and be buried in Ipswich, from which city or its immediate surroundings she was never absent…”

There was no mention of her participation in the Earl Grey Scheme, and no reference to how either she or John had come to make Australia their home. Those days were long gone and the memories buried with her. Though their lives were lived in great contrast to one another, both Anne and Catherine were pioneers. And it is thanks to them, and the other women who bravely forged a new path, that their Irish descendants have helped to build today’s Australia.

Through DNA and research, Terry has been in contact with several other descendants of Catherine and John. He knows he has a lot of American cousins, and cousins still in Ireland, out there. He would love to hear from Hegartys, Fords, Reynolds, Dolans and other branches of the tree who are scattered around the world, and if you think you’re related, please get in touch with me through the Irish Philadelphia website.

Below is the FB Live video presentation I gave for the Irish Diaspora Center.