For Henry, the 3rd Earl Grey (son of Charles, the 2nd Earl Grey for whom the tea is named), it seemed like the perfect solution to two problems he was facing in 1848 as British Secretary of State for War and the Colonies. He was hearing from Australia, where the ratio of men to women at the time was 8:1, that they needed more females to join the population. And at the same time he was being inundated with reports on the terrible overcrowding in the Irish workhouses, where conditions were deplorable even amidst a nation of starving people.

Ireland, no stranger to hard times, was facing an unprecedented period of starvation and poverty. What was once designated as “The Famine” has since been more fittingly reclassified as “An Gorta Mor,” or “The Great Hunger.” But no matter what you call it, people were looking for ways out of the unrelenting destitution and death that had become a way of life.

Workhouses, established after the Poor Law Act of 1838 was enacted, had increased in number to 123 by 1845. But by the time a person showed up on the doorstep of a workhouse, they were out of options. Sometimes families came through the doors together, where they were promptly and permanently separated. Males over 15 in one building, females over 15 in another, children under two to another area, and then children between 2 and 15 housed in yet another space. The only way most people left the workhouse was by dying.

Oftentimes, orphaned children were dropped off at the door, which meant they were out of family to take them in. A child could be considered an orphan if one parent had died, and the other could no longer care for them. Education was supposed to be provided, but in reality there was very little reading, writing and arithmetic being learned. Any child who entered the workhouse, if they survived to adulthood, was looking at a lifetime in there. They would always carry the stigma of having grown up in such a place, and would never be given the education or life skills to survive in the outside world. One report estimated that between February of 1847 and the middle of 1849, the number of children living in the workhouses grew from 63,000 to 90,000.

It’s understandable that Earl Grey thought he had come up with a plan would that would be seen as a viable and welcome solution for some of these young women. The Australian government would pay for the passage of the hand chosen candidates, and he would consult with the Poor Law Commissioners on how to select only the most suitable participants, those who would present as a “more respectable immigrant.”

And it’s also easy to see how the idea of a life far away from the workhouses of Ireland would appeal to these girls. Though most of them would have had no conception of what Australia looked like, or what life there would encompass, surely it couldn’t be worse than what was in store for them if they stayed where they were.

Strict rules were drawn up for those who applied. They had to be orphaned girls between the ages of 14 and 19, of industrious habits and good character, free from all disease, vaccinated against smallpox, educated and unmarried. And they also could not have been born out of wedlock. Because of this last stipulation, every girl listed a father in her paperwork; the records may or may not be accurate. Certainly it was determined that many girls adjusted their ages in their applications because it was deemed better to be younger.

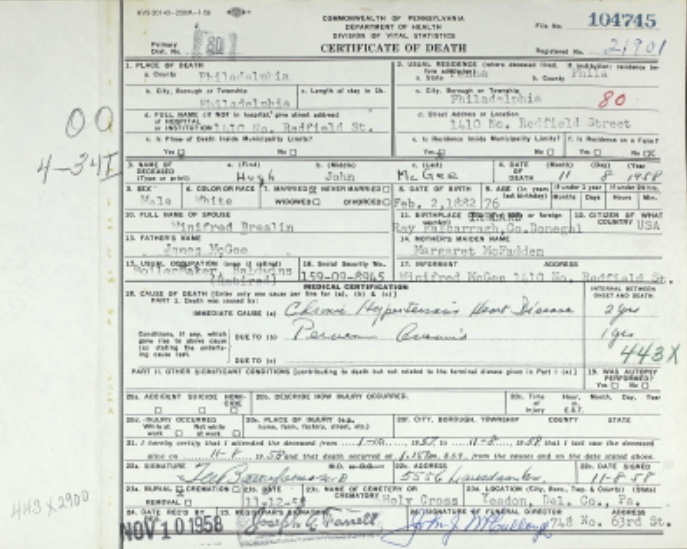

While records from the various workhouses throughout Ireland are sketchy (some workhouse records survive, others do not), the records kept on Australia’s end provide a very good accounting of the young women. Upon arriving in their new country, the girls gave their names, ages, home addresses, the workhouses they came from, their parents’ names and the names of any relatives who had also come over. Whether the information they provided is true or not is an entirely different matter.

The lives these young women were walking into would vary greatly, from both their old lives as well as from what each would experience in Australia. In the two years between 1848 and 1850 that the Earl Grey Scheme was carried out, over 4,000 girls would make the trip. Some ships docked at Sydney, some at Port Philip (Melbourne) and others at Adelaide. Once in port, notices were placed in the newspapers advertising that a ship of “Irish orphans arrived. Applicants desirous of availing themselves of their services are requested to attend in person or by proxy … It is recommended the orphans be removed immediately after the arrangements have been made.”

All of these women were brought out with the expectation that they would work and provide needed female labor to Australia. It was also expected that they would marry a man considered to be of a similar background: an Irishman who had been transported as punishment for crimes that varied from minor theft to murder. Girls that were deemed “difficult” or of “bad character” by the time the voyage was over were banished to Moreton Bay (now known as Brisbane Bay), a settlement that had been developed not just as a penal colony, but had earned the reputation of being one of the worst penal colonies.

For generations, the stories of these “Irish orphans” were hidden away. The women who created successful lives, enjoyed happy marriages and made a lasting imprint on the settlement didn’t want to talk about how they got there. And for the ones for whom life didn’t turn out so well, there may not have been anyone around to pass down their experiences. It’s only in recent years, as descendants of these extraordinary pioneers dig into their family histories, that the stories have come to light and are being heralded.

I first learned about Earl Grey and his scheme about five years ago from my Aussie cousin Carol. My second great grandfather and her great grandmother were brother and sister, and the last time our branches were in contact was probably somewhere in Scotland around 1880. But thanks to modern technology, we can FaceTime one another from our little corners of the world. But it is Carol’s husband, Terry, whose second great grandmother came to Australia from the Boyle Workhouse in County Roscommon. The two of them have done an incredible job putting the pieces of her story together (and it is their photos that accompany this article). Next week I’ll share the journeys of Catherine Hegarty and her sister Anne, and how two lives took completely different turns in Australia.

Below is the FB Live video I did this week for the Irish Diaspora Center’s FB page: