It’s a chill early April day in East Oak Lane. Chuck Connelly is leading the way up a pitch-black stairwell in the middle of a ramshackle barn, a couple of blocks from his home. I can just barely make out his profile. We step out on the top floor, where we can see a little better. Shafts of light lance through cracks in the wall.

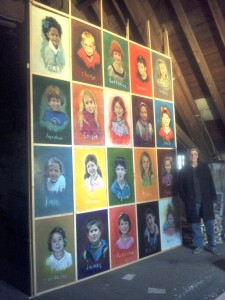

We tread carefully past dusty stacks of books and old classical LPs. A clawfoot bathtub sits incongruously off in a corner. Finally, we arrive in a cavernous space illuminated by an arched window and a utility light. Before us stands a breathtaking work of art: a 10- by 12-foot collection of 20 brightly painted portraits of children, the canvases all bound together in a still unfinished wooden frame.

It takes no time to recognize these children. Their pictures were all over the news in the days and weeks following December 14, 2012. They’re the young, innocent victims of the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in Newtown, Conn.

Connelly, like so many of us, saw the same snapshots in the news. Unlike the rest of us, Connelly was in a position to transform his grief into an incandescent, life-affirming memorial. He is a world-renowned, Tyler-educated artist whose work has appeared in countless galleries, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art. His paintings have invited comparisons to Vincent van Gogh.

Connelly’s colorful career has been the subject of an HBO documentary, “The Art of Failure: Chuck Connelly Not for Sale.” A movie, “Life Lessons”—Martin Scorsese’s contribution to the 1989 anthology film, “New York Stories”—is loosely based on him. In an introduction to a 1991 interview, this is how he is described: “Chuck Connelly is Norman Rockwell on acid—a maverick narrative painter pushing the limits of myth into a modern malaise all his own.”

Connelly—tall, craggy-faced, and somewhat rumpled—stands before his ambitious project, the fingers of one hand lightly clinging to a cheap Korean cigarette. He is given to moments of deep cynicism when he talks about his career and his troubled relationship with the art world, but when he looks at this bigger-than-life work, his comments take on an air of reverence.

“I worked every day since it all started, just a couple of days after the tragedy,” Connelly says, and he points to one portrait in particular, two down from the top and two in from the left. It’s a blonde girl with plump, baby cheeks and sparkling blue eyes. It’s Emilie Parker, just 6 years old at the time of her death.

“I started to do the one, Emilie, when it first happened. Her face was everywhere. I just thought … what a tragedy. So I painted her. Then I made Dylan (Hockley), and then I thought … you know what? I gotta do them all. Emilie probably took the longest. As I did the others, I would often go back and make her fit in with them. Some came right off the brush. Others, even Emilie, went through a lot of stages. I didn’t have a plan.”

Drawing inspiration from the many photographs that emerged in the days after the shooting, Connelly toiled away on the paintings in his rambling Victorian home, a chaotic space where paint spatters dot the hardwood floors, and dozens of canvases stand propped up against the walls like shingles. It took about a month before he was finished painting them all.

Which doesn’t mean he’s finished with the project. Not at all.

“I’m not done until I get this someplace and people stand in front of it,” says Connelly. “That is my goal. It needs to be somewhere. It’s not really finished until it’s stabilized on a real wall. I don’t see one portrait as a painting. I consider this all one piece. To me, that’s the painting.”

Enter neighbor Marita Krivda Poxon, author of the recently published history, “Irish Philadelphia.” Poxon came to know Connelly several years ago as a result of one of his projects, a series of paintings of the grand old houses of East Oak Lane. One of those homes was Poxon’s. She bought the painting, and then she and the artist became friends.

Connelly’s skill lies in creating indelible images, but, Poxon says, he wasn’t sure how to find a permanent home for his 10- by 12-foot masterwork. “I’m just the artist,” he says. Poxon, on the other hand, is a career librarian. Research is something she knows well. She put her skills to work to find a place for her friend’s project.

The one obvious destination for the outsized project: Newtown, Conn. But that’s where the story takes an unexpected turn.

Or perhaps not so unexpected. In the months following the shootings, Newtown was on the receiving end of thousands of gifts and millions of dollars in donations. The town was overwhelmed. The day after Christmas, the word came down: Please, no more.

“Our hearts are warmed by the outpouring of love and support from all corners of our country and world,” First Selectman Patricia Llodra told the press. “We are struggling now to manage the overwhelming volume of gifts and ask that sympathy and kindness to our community be expressed by donating such items to needy children and families in other communities in the name of those killed in Sandy Hook Elementary on December 14.”

Nevertheless, Poxon reached out to Jennifer Rogers at Newtown’s Cultural Arts Museum in the hope that there might yet be a suitable space for Connelly’s project. (Poxon tracked her down through a reporter at the New York Times.) An organization called Healing Newtown had set up a gallery featuring artwork from around the world in a rented building in the middle of town. Healing Newtown donated the space to the Cultural Arts Museum. The gallery drew in dozens of local residents in the weeks after the shooting. It seemed like it could be a good fit.

“They want to accept it but they didn’t have a place for it at this point,” Poxon recalls. “Unfortunately, they were about to be kicked out of the donated space. Jennifer told me, Newtown wants this painting, but they have no place to put it.”

Rogers suggested trying finding space in a nearby museum. Poxon contacted the Mattatuck Museum in Waterbury, but again, no luck. There was no room for anything that big.

The museum director then put Poxon in contact with the agency that displays art at the state capitol. But, again, no luck … but for a different reason. Government officials were afraid that some of the parents just weren’t ready to deal with such an emotionally charged piece of art. “They know the families firsthand. Some of the families would love it, but some of the families wouldn’t. It might be too much for them.”

Which leaves Poxon in the position of trying to find a temporary home for her friend’s massive tribute somewhere in the Philadelphia area.

For his part, Chuck Connelly is frustrated by the lack of progress. He understands that some Newtown parents might find it painful to deal with the public display of their children’s portraits, but he still holds out hope that his labor of love will eventually find a home in Newtown, and in the meantime in a space closer to home.

Until that day comes, the massive work will stay where right it is. “I love this space,” he says. “It’s like this secret little chapel that no one gets to see, and even if no one is seeing it, it’s here. Here they are.”