When the call came over the police radio, Tim Brooks knew it was something big. He could feel it. A boat capsized off Penns Landing. There were survivors in the Delaware.. “It’s not something you hear every day,” says Brooks, a 19-year veteran of the Philadelphia police department and a detective with the bomb squad. “If you’ve been a cop for any amount of time you get some sense of what’s going to be legit and this sounded legit.” And serious.

Brooks was with his partner and an ATF agent at ATF headquarters at Customs House at Second and Chestnut a year ago–on July 7, 2010—when they heard the call. Just a couple of blocks away, a 2,100-ton city-owned barge picking up sludge rammed a stalled sightseeing boat operated by Ride the Ducks with 37 tourists on board, sending the crew and passengers into the murky, fast-moving waters of the river.

That’s what Brooks saw when he and his colleagues arrived at the scene just a few minutes later. He remembers it like a photograph: heads bobbing like buoys in the Delaware, many of them terrified children frantically swimming toward shore, the ravaged Duck boat now sitting at the bottom of the river. “You had to take a moment,” recalls Brooks. “There were so many people in the water. You didn’t know where to begin. It seemed overwhelming.”

But that’s where the thinking stopped and instinct took over. Brooks quickly shed his gun, his wallet, shoes and keys and jumped into the water, his eyes on a woman and three children struggling to grab on to a row of wooden pylons about 20 yards offshore.

“The first one I reached was a young girl, maybe 10 years old,” Brooks recalled. “She wasn’t panicking, but I could see she was upset.” He grabbed hold of her and helped her grasp one of the pylons.

By this time, a Coast Guard boat had reached the group, but couldn’t get close because “if a wave came or the current switched, you could get crushed,” says Brooks. The Coast Guard crew tossed a rope out, and Brooks put the little girl’s arm around his neck and swam her to the boat where she was pulled on board. “Then I went back for the other girls,” he says, “and a group of Navy Seals in a small boat arrived.” Fortuitously, the Seals were visiting Philadelphia from Reston, Virginia, for Navy Appreciation day. Since their vessel was an inflatable Zodiac, they were able to pull alongside the group and Brooks helped pull the woman and the other children out of the water.

There was no room for Brooks in the Zodiac so he swam back to the Coast Guard boat. “I was pretty tired when I got back. Someone told me that I had been in the water for 15 minutes which is a long time to tread water. But I couldn’t have told you how long I was in there—I was a little busy,” he says, laughing.

Sitting outside the small office of the city’s bomb disposal unit in northeast Philadelphia, the sound of bullets and explosives punctuating the air, Brooks concedes that the case was unusual for him—he’s an investigator whose milieu is fire, not water. But he still considered his actions all in a day’s work. “I don’t feel like I did anything special. It’s my job,” says the tall, affable Brooks, whose family tree, like that of many descendants of Irish immigrants, is crowded with cops and firemen.

But other people thought that what he did was more than special. They thought it was heroic. One of them was Philadelphia Homicide Detective Jack Cummings who nominated Brooks—without his knowledge—for a Congressional Medal of Honor Foundation award. The organization, chartered by Congress in 1958, consists exclusively of recipients of the Congressional Medal of Honor, the highest military decoration given by the US. These same honorees, most of whom risked their lives in combat, choose the recipients of the Citizen Service Above Self Award every year.

“He did it in December and told me in January,” says Brooks. “He said he just wanted to let me know that ‘that was a good thing you did.’”

In March, the Foundation announced that Brooks was one of three people from around the country—including a Boston school crossing guard who died after throwing herself in front of a car to protect a child—chosen to receive the award, which is bestowed at a ceremony at the Tomb of the Unknowns at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia. Marine Lt. Col. Harvey C. “Barney” Barnum, who received the Medal of Honor for risking his life to save his beleaguered battalion when they were pinned down by enemy fire at Ky Phu in the Quang Tin Province in Vietnam in 1965, presented Brooks with his award.

“I never in a million years thought I’d ever get something like that,” says Brooks. “I still don’t think I deserve it. Millions of people do tremendous things every day and I’m not one of them. I feel humbled to be considered among them.”

Brooks spent three days in the Washington area with the Medal of Honor winners. “We were throwing back war stories like we were old friends,” he says grinning. He and the other honorees met President Obama at the White House. The days were already fraught with emotion, but Brooks had another reason to be grappling with his feelings. The day on which he received his award was the first year anniversary of his father’s death. “It still gets to me,” he confesses, his eyes watering. “I carried his picture in my pocket. I really think the date was no coincidence.”

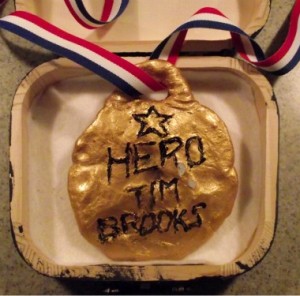

Brooks was carrying something else with him too. One of the children he rescued, a little girl named Lily, had surprised him at the ceremony with her own medal—homemade from clay, painted gold, and even inscribed with his name. (See a photo of Lily and her hero here. ) How they met—both the first and second time–was serendipitous. “When the story appeared in the paper, my wife Shannon’s hairdresser told her she was dying to tell her something. She said, ‘The woman your husband saved is one of my clients. She was in here the other day, crying, and she said she was going to contact the police department because they want to meet him.’”

When they finally did meet, Lily’s mother gave Brooks a copy of the letter that her daughter had written to the Congressional Medal of Honor Foundation. “I read it and we sat around sobbing like a bunch of two-year-olds,” Brooks confesses sheepishly.

In Arlington, he showed Lily’s medal to Col. Barnum. “We were about to have our official pictures taken and I said to him, ‘Colonel, can I leave this on? He said, ‘If you don’t, I’ll break your arm.’”

Brooks is the only one in the official photos wearing not one, but two medals. It’s hard to tell which he treasures more.

“As you can see,” says Brooks, “I’m really humbled by this whole thing and I’m not comfortable talking about it. But I wanted to speak out because I am a product of the training I got in this police department. In my opinion, this is the most professional law enforcement organization on the planet, though sometimes the media tends to highlight the negative. The truth is, cops from here to Alaska are doing heroic things every day. I didn’t do anything special. I was doing my job. I know that any of my fellow police officers would do the same thing.”