By Michael Carolan

The Dublin crowd last week was undoubtedly grateful to have once again—after Kennedy, Reagan, and Clinton to name a few—a U.S. President proclaim his Irish roots and with such precision.

Thanks to an internet genealogy service, the missing apostrophe in Obama has been located: his maternal great-great-great grandfather is Fulmuth Kearny, a Protestant bootmaker from Moneygall, County Offaly, who left Ireland during the Famine in 1850.

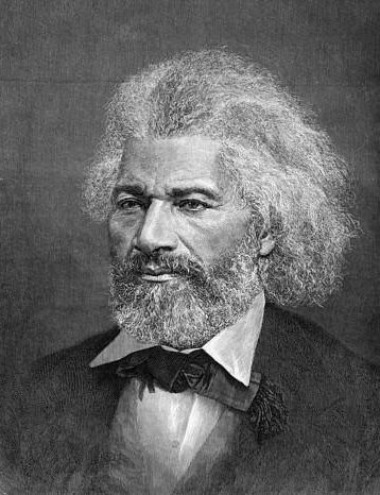

The President provided the throngs of well-wishers at College Green genealogical context by paying fitting tribute to a contemporary of his ancestor: Daniel O’Connell, the Irish patriot who profoundly influenced Mr. Obama’s own historical hero—the great black abolitionist Frederick Douglass.

It was, as Mr. Obama noted, an “unlikely friendship” forged between the two men. The Irishman peacefully worked for the self-rule of millions of Irish; the former slave pushed for the freedom of millions of African Americans in bondage.

What Mr. Obama failed to note was that 166 years ago the “Emancipator” Douglass and the “Liberator” O’Connell were not always so friendly. In fact, their respective peoples had a tumultuous relationship fraught with labor politics, hatred, and violence, and right here in Philadelphia.

It is true that Douglass, born into slavery himself, escaped to Ireland in 1845 where he met his hero O’Connell, then in his 70s. The two men were fond of one another, to sure, both hating the institution of slavery. But Douglass returned to a country soon besieged by nearly two million Irish Catholics fleeing centuries of religious persecution and more immediately, the horrors of the Famine.

What they wanted in America were jobs. But African Americans in mid-19th century Northern cities had the run on the economy’s low-paying menial jobs and hence, there was competition.

Douglass complained in a speech to a New York anti-slavery society nine years after he returned from Ireland: “Every hour sees us elbowed out of some employment to make room for some newly-arrived emigrant from the Emerald Isle, whose hunger and color entitle him to special favor.”

“These white men are becoming house servants, cooks, stewards, waiters, and flunkies,” Douglass told the audience. “…I see they adjust themselves to their stations with all proper humility. If they cannot rise to the dignity of white men, they show that they can fall to the degradation of black men.”

“In assuming our avocation,” the Irishman “has also assumed our degradation,” he added.

Indeed the Irish “laborers,” like Obama’s ancestor, were often called “white negroes” to denote the exploitative, backbreaking jobs at which only blacks were previously willing to work. It was not always clear on which side of the color line an immigrant like Fulmuth fell.

Was he black or white?

Sidney Fisher, a prominent Philadelphian of the time, wrote that the Irish did not get along with blacks “not merely because they compete with them in labor, but because they are near to them in social rank. Therefore, the Irish favor slavery in the South . . . it gratifies their pride by the existence of a class below them.”

Meanwhile, the newly arrived Famine Irish for whom Daniel O’Connell spoke had little sympathy for the anti-slavery cause itself. That’s because they mistrusted the Protestant majority of the same ilk that had persecuted them for centuries in Ireland.

The gulf between the average Irishman and the Yankee Abolitionist leader was too great to bridge: their link to antislavery circles there (Britain abolished slavery in 1833) further alienated the Irish. The sudden British moral reformers were, after all, hypocrites, blind to their own centuries old, slave-like oppressive practices in Ireland.

In Philadelphia, the African-Irish problem dated back to early 19th century when Ulster (Irish) Protestants and free blacks arrived in the city in great numbers. The firehouse was the social and political center of neighborhood life and African Americans were refused their own department. Then one night in August 1834, a group of young black men attacked the Fairmount Engine Company, running off with equipment. Three days later, the city’s first full-scale riot erupted.

What newspapers called a “lunatic fringe” attacked an amusement hall that housed a carousel called the “Flying Horse,” a popular entertainment for both blacks and whites living crowded together in the working-class boarding houses near 7th and South Streets.

Correspondents claimed that a mob threw a corpse from its coffin, cast a dead infant on the floor, “barbarously,” mistreating its mother. By the end, two were dead, many beaten, and 20 homes and two churches destroyed. Twelve out of the eighteen arrested had Irish names.

A committee assigned the cause to employers hiring blacks over whites, with many “white laborers out of work while people of color were employed and able to maintain their families.”

The labor, racial and economic strife continued periodically in Philadelphia’s urban immigrant enclaves—in places like Kensington and Southwark and Moyamensing—through the 19th century.

In 1842, mobs burned down the Second African Presbyterian Church and Smith’s Hall on Lombard Street—the site of abolition lectures since Pennsylvania Hall was destroyed in the riots of 1838. A plaque today commemorates the event.

But there was also the established nativists—English and Scotch-Irish Protestants and Quakers (who had their own political party for a time “the Know-Nothings”) who disliked the new Irish Catholic immigrants and associated them with the African Americans as well, exploding into the 1844 Nativist Riots in which 2 were killed and 23 wounded.

“The City of Brotherly Love” Frederick Douglass found not, proclaiming that one could not find anywhere “a city in which prejudice against color is more rampant than in Philadelphia.”

For Daniel O’Connell’s part, the Repeal movement for Irish freedom from England needed capital and Southern slave-backed money poured in. This had O’Connell waffling between speaking for the anti-slavery cause and alienating his Irish-American support and keeping the tainted donations.

At one point, anti-slavery advocates were furious with O’Connell. The prominent abolitionist Wendell Phillips called him “the Great Beggar man,” fuming that the O’Connell “would be pro-slavery this side of the pond. He won’t shake hands with slaveholders, no—but he will shake their gold.”

So when President Obama proclaimed in Dublin that “When we strove to blot out the stain of slavery and advance the rights of man, we found common cause with your struggles against oppression,” that common cause—both of them—was hard fought, and indeed eventually successful. African Americans and Ireland were eventually free.

And while the President’s words were profound at just the right moment in history—his Irish and African roots unified—they didn’t tell the whole history.

Michael Carolan teaches literature at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts. His father was born in Philadelphia, the great grandson of a Famine emigrant who arrived in 1847 from County Meath and lived in Feltonville. His story can be found here. Michael is the recipient earlier this year of the first annual Crossroads Irish-American Writing Prize. His website is michaelcharlescarolan.com