A couple of years ago, a young Irish-American filmmaker named Shawn Swords from Glenolden trailed a popular Irish-American band around and produced a critically acclaimed documentary called, “Blackthorn, It’s an Irish Thing,” which appeared on UPN.

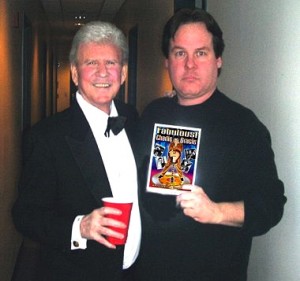

Last year, Swords completed a documentary of Philly rock and roll pioneer Charlie Gracie, whose “Butterfly” knocked Elvis from the top of the charts in 1957 and sold more than 3 million copies worldwide—without benefit of the internet. “Fabulous” was picked up for World Wide Distribution by Oldies/Gotham/Alpha distribution and was a huge hit two summers ago during a PBS fundraiser.

This month, Swords, who went to film school at 32 and now steers Character Driven Productions (Conrad Zimmer, Blake Wilcox, Paul Russo), debuts a brand new documentary, this one on the American Bandstand Philly years with Dick Clark, on September 27 at the Wildwood By the Sea Film Festival at the Wildwood Convention Center.

But if you think “Wages of Spin” is a feel-good trip down memory lane with Bobbie Rydell, Chubby Checker, Frankie Avalon, Jerry Blavat, Justine, Eddie, Arlene and the other and all the other Bandstand dance regulars, you’re in for a shock. The same one I got when I caught Swords’ trailer on YouTube.

It opens with a black screen, like a chalkboard, on which is scrawled the word, “Payola,” with a definition for those who have no memory of the ‘50s music scandal, the origin of the term “pay to play”: “A secret or private payment in return for the promotion of a product, service etc, through the abuse of one’s position, influence or facilities.” Then you hear the voice of Artie Singer, who wrote the popular Danny and the Juniors’ hit, “At the Hop.”

“Where do you think Dick Clark made all his money? Initially where do you think he made it? From guys like me.”

Singer is looking at the off-screen interviewer. He raises his arms in the classic “but wait” move. “Granted,” he continues, “I can’t say anything derogatory. I can’t say anything bad because I owe my success in the record phase of it to Dick Clark.”

He had to “love the guy,” Singer tells the off-camera Swords, because without him, “there would have been No ‘At the Hop,’ no Danny and the Juniors.”

And by “without him,” Singer says, he means without Clark taking 50% of the publishing rights to the song. If the record producer hadn’t given it to Clark (as a gift, he later said, because they were friends) there’s a good chance that “At the Hop” would have gotten no play on what was the most popular teen program in the ‘50s.

Oh, say it ain’t so! America’s oldest teenager, the fresh-faced host who squeezed between two Philly teens every day from 3 to 4:30 PM to introduce the latest hit record or musical heartthrob, the guy who’s been counting that ball down on Times Square every New Year’s Eve? Dick Clark? Making hay to play?

To hear Swords tell it—and he’s talked to the players and read the transcripts—it was big time. He first came across the story when his friend, Paul Moore (formerly of Blackthorn, now of Paddy’s Well) asked if he was familiar with the story of Charlie Gracie. “Charlie was a talented musician, but he wound up being blacklisted back in the ‘50s, says Swords. “Charlie has a number one hit, at 19 years old, went on tour for a year, appeared on he Ed Sullivan Show, with [teen rock show DeeJay] Allan Freed, Dick Clark, then comes back home to Philadelphia and he’s not getting royalties. The record sold 3 million worldwide.”

Gracie discovered that Dick Clark owned 25% of “Butterfly.” Gracie sued the record producer and got $50,000, but that was the end of his career. Though he signed with a new label, he couldn’t get airplay. “He knocked Elvis off the charts and he couldn’t get airplay,” Swords says.

Digging deeper, Swords discovered that according to Congress, Clark was given somewhere in the neighborhood of 160 copyrights with the implied guarantee that those songs would air on Bandstand. But during the payola hearings before congress in 1960, Clark denied taking payola to play songs. In a New York Times article written at the time, Clark is quoted as telling the House Special Subcommittee on Legislative Oversight, “I have not done anything that I think I should be ashamed of or that is illegal or immoral, and I hope to eventually convince you of this. I believe in my heart that I have never taken payola.”

And in fact, says Swords, even if songwriters or producers never handed a fistful of cash over to Clark, he got paid. Instead, as was the case with “At The Hop,” he was given copyrights to songs, which meant that he benefited financially from their rise to the top of the charts. The New York Times report said that the Committee produced figures showing that over a three-year period, Clark had received $167,750 in salary and $409,020 in increased stock values, on investments of $53,773. That led one legislator to remark that if Clark hadn’t gotten payola, he’d certainly gotten plenty of “royola,” referring to royalties.

But by the time of he hearings, Swords says, Clark had divested himself of many of his holdings, including as many as 30 various businesses related to the record industry (as documented by Congress), so that the committee gave him nothing more than a slap on the wrist. Other DeeJays weren’t so lucky. Allan Freed lost his job and though he received only a small fine, his career was over; he died penniless at 43.

“Clark took the money from the divestiture and started Dick Clark Productions which became one of the most profitable independent TV production companies of all time,” says Swords.

While it took the filmmaker some time to uncover this chapter of the history of rock and roll, it really wasn’t hidden all that well. In fact, one of the producers of the film is John A. Jackson, author of the book that laid out many of the details, “American Bandstand: Dick Clark and the Making of a Rock ‘n Roll Empire.”

“John wrote a fantastic book, one of my favorite books, but it barely showed up on the radar,” says Swords. “Why isn’t more of this public knowledge?” One reason, he suspects, is that it’s hard to get corroborating evidence from some of the singing stars of the era, with whom Clark still has dealings. “Some of them are still getting checks from him for appearing in Branson [the Missouri musical destination where yesteryear’s idols play to packed houses of nostalgic audiences],” says Swords. Nevertheless, Swords has at least 7 interviews on tape, like Singer’s, detailing what went on, but that’s out of about five dozen interviews. “They would tell me what happened, but a lot of them just stopped talking when the camera was rolling,” he says.

While Swords admits he likes digging into “abuses of power,” he doesn’t want to be typecast as a muckraking filmmaker. As a boy, he attended Girard College where he watched “the epic films” on old projectors “because they could get better rates on the old films,” he recalls. “We wouldn’t see the first-run films like the karate movies everybody loved back then. But I loved those old films, great English pictures on Cromwell and Henry the Eight, the David Lean movies, like ‘Bridge Over the River Kwai,’ ‘Lawrence of Arabia,’ and ‘Dr. Zhivago.’”

“I like the art films too, and have a real affinity for John Ford films, which are very melodic and emotionally impacting. I love the great action films and the film noirs, where there’s a great story.”

It was those kind of narrative films Swords planned to make when he went to the New York at 32, after getting out of the Navy, working two jobs to put himself though New York Film Institute. In fact, he’s working on a new screenplay now. “I worked most of it out during the two hour walks I take every day,” he says. “The whole plot, twists and everything. If I could sit and write all the time I’d be pretty good. I can really kick them out. Right now I’m tightening up one of my better screenplays and working on a couple of pilots, including one that’s a black comedy.”

He has six finished screenplays that he’s going to shop in LA by the end of the year. “I’ have had two offers for talent representation,” he says.

And when we talked a few weeks ago, Swords was still putting the finishing touches on “Wages of Spin,” which meant weeks of “being nocturnal,” while readying the documentary for The Wildwood By the Sea Film Festival, which he co-founded with his executive producer Paul Russo. “I have black circles under my eyes,” he admitted.

Don’t let it be for naught. Check out “Wages of Spin,” Saturday, September 27, at the Wildwood by the Sea Film Festival. If you can’t make it to the shore, there will be four screenings of “The Wages of Spin” at The Elaine C. Levitt Auditorium, 401 S. Broad Street (Avenue of The Arts) at: Noon, 2 PM, 4 PM and 6 PM. on Saturday, October 11. Admission is $10 at the soor. Artists featured in the documentary will be present at screenings.

“The Wages of Spin” will run continuously from 5 P.M until closing on several screens at Rembrandt’s Bar and Restaurant, 741 N. 23rd Street in Center City, on October 18 with several music and entertainment industry notables in attendance.?Tickets are $30 and are available at the door.